Friday, my first day in London, I took a bus to the Truman Brewery, home of Lulu Kennedy’s Fashion East, a well-established platform for new talent and where a bar featured four varieties of cocktails. It was hard to choose, but I went with a margarita. The show consisted of three designers, and I liked the terse shapes of the last, Olly Shinder, a 2022 graduate of Central Saint Martins, who reinterprets workwear, like a 1950s nursing uniform as a square-necked, box-pleated dress in black wool. Shinder, in the airy language of many brands today, describes his work as “a product of the cultural networks that thrive at the intersection of the city’s fashion establishment, art institutions, and queer night spaces.” What I saw was more modest.

From Fashion East, I went along the Thames to a place near the Houses of Parliament, where Richard Quinn had contrived a wintry night scene, with street lamps and fake snow piled before a building façade with his name seemingly carved in stone. More snow fell as the models walked like 1950s mannequins, without irony. Quinn, in the tradition of English society designers like Bellville Sassoon and Norman Hartnell, makes elegant clothes. They are undeniably pretty and well-done, but the conventional feminine cuts and trims made me think of another London designer, the fictional Reynolds Woodcock, in the movie Phantom Thread.

An hour later, at around 9 p.m., I was squeezed into a seedy club in Islington, or, as the notes for Dilara Findikoglu’s show put it, “Here, what men of power would call a toxic atmosphere is as freeing to breath as alpine air.” Young London designers have loved showing in clubs for decades; you can hardly be a rebel without one. Findikoglu pursues the idea that every corseted jacket, every skimpy, near-naked dress is an act of feminine mutiny against an oppressive patriarchy. Yet when I look at some of her clothes, especially the tailoring or an embellished high-necked top, I think of Alexander McQueen, only he did them better and with artistic context. More convincing were her body-skimming dresses, their surface broken by pale feathers or safety pins or loops of braided blond hair.

But here’s the thing: Are any of these ideas modern, and I mean the party frocks and reworked uniform styles? With few exceptions, fashion has lived at the same intersections of art, culture, and identity for at least a decade, yielding little new insight or direction. Similarly, we’ve seen plenty of collections from young designers who attempt to explore their heritage or contrast it with a historical mode, yet the results are often redundant. Given the harshness of social media, I don’t expect designers to be as political as they once were. Nor are we likely to see a consensus around a single designer or brand, as we did in the ’90s (John Galliano at Dior, for example) and later (Alessandro Michele at Gucci). Remember, fashion is a reflection of society. No one expects consensus there, either.

Yet, as the London shows progressed through Monday — they ended in the evening with Burberry, flying an elitist flag — I met two remarkable young designers who gave me hope: Steve O Smith and Yaku Stapleton, whose two-year-old brand is called Yaku and who prefers his first name (a family diminutive of Jacob). Both men graduated from the M.A. program at Saint Martins, and Smith got his undergrad degree from the Rhode Island School of Design. I also had an interesting chat with the Irish designer Michael Stewart of Standing Ground, which has already won acclaim (and an LVMH Prize last year) for Stewart’s modern and elegant clothes. He didn’t show this season to prepare as a finalist for the International Woolmark Prize, in April, and to save money for possibly showing during Paris couture week in July. And I saw a number of excellent shows, notably by Paolo Carzana, whose work took a leap forward this season, and the versatile Steven Stokey-Daley.

First, let’s consider Smith. I met him on Saturday, on the top floor of a faded apartment block in northeast London, where he lives and works with his partner, Liren Shih. Meeting them reminded me that some of the best fashion-reporting experiences of my career have happened in London. In bare-bones studios, with open and smart young designers — like the first time I met McQueen, in 1997, in his old Hoxton Square studio. In nearly every case I was aware that something significant was taking place, that I was encountering someone who not only had an original idea but also the technical skills and imagination to bring it to life.

Smith’s idea is to make clothes (mostly dresses and some tailoring) that impart the feeling and movement of an abstract drawing. “They exist as drawings,” he told me as we stood on either side of a big work table, overspread with small sketches and a dress of black-and-white organdy and tulle. “I like to think of them as drawings. They should be special.”

He begins with a drawing, then enlarges it to life size, then starts to build the design of a dress. Behind him, on a dress form, was a strapless gown in white organza with an extremely lightweight pannier — to extend the hips, reduce the waist — and an appliquéd “drawing” in black crêpe de Chine spilling over the dress. Amazingly, the crêpe was cut out as one piece, then hand-sewn onto the organza. Initially, Smith’s aim was to show contrast, but now he’s going for tone — that is, a sense of shadow and depth by combining sheer fabrics in gray, black, and white.

It’s a paradox that Smith is using one of the oldest skills in fashion to create something new. In the past, most houses had people sketching a collection. Today, few creative directors can draw, sew, or cut a pattern. “The New Look was made from a drawing,” Smith said, referring to Christian Dior’s postwar volumes. “You can tell. You’d never get that form without a drawing.”

A finalist for this year’s LVMH Prize, Smith doesn’t have plans to show any time soon. Nor does he need to. He received much attention after the actor Eddie Redmayne and his wife, Hannah Bagshawe, wore his clothes to the Met Ball last year. His small team is currently at capacity for orders, all of which are custom. Prices start at around $12,600.

What is so striking about his practice is that it has room to evolve. “And it’s about doing that slowly,” said Smith, adding, “It would be amazing to create an atelier of like-minded people who are being paid a fair wage. How many jobs use AI? Making things with your hands is going to be super important, and it’s so central to the British identity.” He said his next plan is to work in color. “We want to do a Matisse as it appears in the painting,” he said.

“Wouldn’t that be difficult, with all those colors?” I asked.

“Yeah, but we love it. It’s all just a problem to solve,” he replied.

When I went to see Stewart in his shoe-box-size studio, four or five people were working on his collection. He showed me a full-length coat in red melton that featured one of his signatures: small beads tightly inserted along a seam or in channels. He’d cut the sleeves of the coat on a curve and used the bead-filled seams to enhance the shape. Touching the melton, he said, “It’s not the most glamorous, but it holds up to a lot of handling. And I think it looks modern.” He’s also developed a superfine knit that performs a lot like shapewear, and he’s done his bead technique with those pieces as well.

Like Smith, Stewart questions the payoff of showing in London, where the tendency among writers and others is to seek the cutting edge. But, in my view, his style, and that of Smith and Yaku, is the cutting edge. “There still is that cool London vibe,” said Stewart, who spent three years as a dog walker between finishing college and starting his label. “I just want a beautiful cut and fit. And I’m not afraid of that. I think a lot of new designers are afraid — first, of their aesthetic not looking modern. But if you have a great silhouette, it will be modern — if you do it the right way. And, second, it’s really hard and expensive to do a good fit, because you have to rework it a lot.”

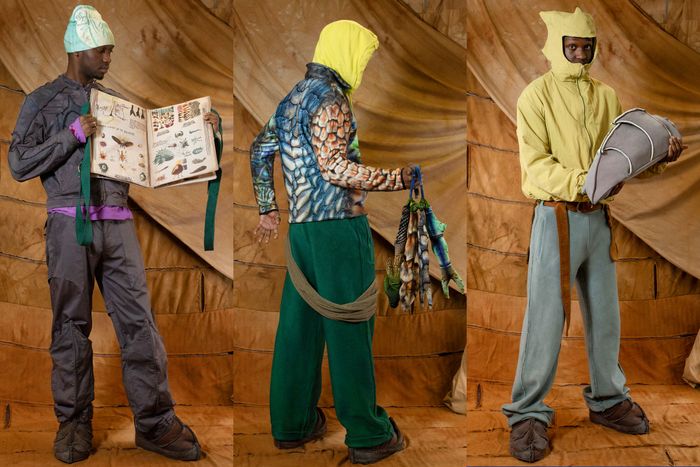

Yaku’s idea is so simple it’s genius. It combines streetwear and the visuals and narratives of role-play games. “There’s a group of people who are really into RPG, who also came up in streetwear and weren’t exposed to high fashion at a young age,” he said. Yaku, who is 27, began playing Roomscapes when he was about 8. But what’s unique about the brand, which he produces with a small team of part-time designers and interns, is that it’s fashion through the sci-fi aesthetic of Afrofuturism. “We were defining ourselves online,” he told me, “but then you could pop back into real life and you could imagine more, play more.”

The upshot is vividly colored streetwear in often fantastical forms — the hint of a dragon’s scales, say, on a puffer — that are nonetheless tangible. Yaku staged a presentation with a group of actors role-playing on a “limitless island.” I told him I found the clothes and tableaux completely strange — which, of course, in fashion is high praise. “I mean, the clothes are strange,” Yaku said. “They’re not regular-looking clothing.”

He paused. “It’s a tricky one. If you say streetwear to someone in our school, it’s an insult. But it’s a foundation for us. There’s not really a word, though, for the progression from streetwear. There’s no language for it yet.”

And how often does that happen in fashion — that you get to be part of inventing your language?

Both Yaku and Paolo Carzana are benefiting from a new foundation set up by Sir Paul Smith, mainly to provide mentors in law and business and also studio space. “At the moment, it’s an industry oversubscribed with creatives,” said Sir Paul, before Carzana’s show on Sunday night in the Holy Tavern pub in East London. To survive, you have to sharpen both your ideas and your business sense.

Carzana plainly did that this season. This was his most substantial collection, richer in color (all from natural dyes like logwood, madder, turmeric, and cochineal) and textures, including pleating and ruching. Carzana is a very particular designer, probably closer to an artist in his practice, and there are moments when I fear that he might have one idea, his poetic, distressed Byron look. But I think not. Look at the leap his designs took this season.

All in all, the leading London lights, like S.S. Daley, Simone Rocha, and Erdem Moralioglu, put on solid shows, with Rocha and Daley focusing on wardrobe building and Anglo-Irish classics, including (from Daley) a nice salute to the evergreen style of Marianne Faithfull (a cool peacoat over a loose, ruffled white cotton blouse). Rocha’s collection had an appealing, tough-girl edge to it, with bike chains and locks as closures for coats, and shapely biker leather and rough faux fur for minis and coats. Moralioglu commissioned the painter Kaye Donachie to create portraits for straight-line dresses (some are appliquéd, others digitally printed), and he invoked a line from Virginia Woolf for all the dreamy ocean blue. The best bets, in my book, were blue-green shifts in a broken-in jacquard with a black abstract detail out front. His clothes also have a sculptural roundness, an emerging fall trend.

After shoestring shows in pubs and clubs, and RPG actors, Burberry felt almost orgiastic, a Guy Ritchie taste of The Gentlemen, courtesy of the brand’s creative director Daniel Lee — who is rumored to be leaving — and held in the splendor of Tate Britain. As Lee said in his show notes of the English outdoor gear, fuzzy sweaters, and chic velvet pantsuits, “It’s that great Friday-night exodus from London. Long rainy walks in the great outdoors to disconnect and day trips to grand stately homes.”

If Lee were ironic — if we lived in ironic times — that sort of elitist stuff might work, but it just seemed old and off-putting. There were some good-looking items in the show, notably those velvet pantsuits (shades of Mick and Marianne), but do we care? What Burberry lacks is cool, but more than that, it needs English irreverence.

I did love that the cast included the actors Richard E. Grant, who played a surly footman in Gosford Park, and the great Lesley Manville, who played Woodcock the couturier’s long-suffering sister.