For over 30 years, Cathy Horyn has been a prominent voice in fashion, offering backstage insights, runway critiques, and thoughtful analysis of style’s ever-changing meaning. To mark a decade of Horyn’s invaluable contributions at the Cut, she recently sat down with editor-in-chief Lindsay Peoples for a conversation reflecting on what’s been learned and what’s been worth celebrating along the way.

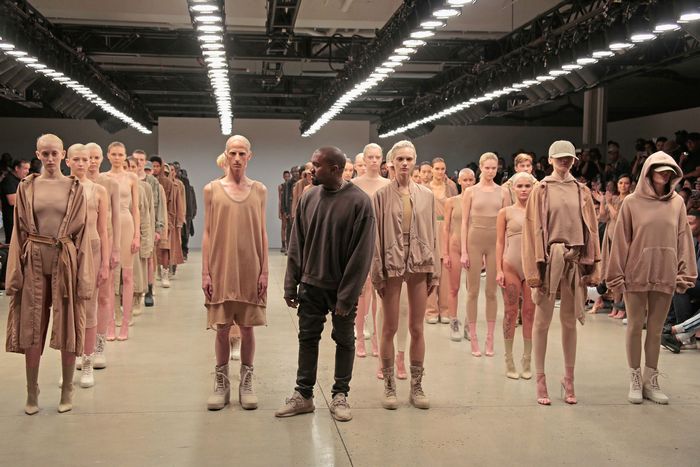

Lindsay Peoples: Let’s start with your 2016 review of Kanye West’s Yeezy show at Madison Square Garden, which you were assigned to cover for your first Fashion Week at the Cut. You said that the show’s problems reflected “the general state of the fashion world — in particular, the sense that an experience often begins with delight and almost always ends with a feeling of nothingness.” Looking back on that show, which was a cultural moment, and Kanye, who has undeniably been a force in fashion — albeit a hugely controversial one: What did you think of him then, and how do you feel about him now? Has your perspective shifted after witnessing so many Yeezy shows? [Editor’s note: In February, after this conversation took place, West posted his latest series of misogynistic and antisemitic statements.]

Cathy Horyn: It’s hard to believe we’re still talking about West, given his recent comments and his final show in Paris in 2022, which was the last straw for most people. It’s as if we’re talking about a different person and a different time. Back in 2016, the show was certainly a spectacle, which West initially was good at. We were in the Garden, and there were thousands of people, because he had invited the public. And the presentation was ambitious, with his music and this massive assembly of models, around 1,500. As for the clothes, one color stood out — brown. He always had a thing for very washed-out, monochromatic tones. At the time, in an arena, it was mesmerizing to see that.

We’d already seen a couple of West’s shows. The first, in New York in February 2015, was overseen by the performance artist Vanessa Beecroft and had a militaristic formation to the cast, a trademark of hers. Those early shows were interesting, even if the clothes weren’t exactly new. Another effective show was in Paris in 2020, at the former French Communist Party headquarters, an incredible building by Oscar Niemeyer, the modernist architect. Again, people in the surrounding neighborhood could see the show because it was outside.

But my feeling about the show at the Garden still stands: There was this big spectacle, but at the end of it, there was little feeling or substance. Having covered fashion for many years, I’ve seen that happen a lot. There’s no long development. Everything seemed so random with West: You see one thing and then something else. There’s not much of a through-line. The customers for Yeezy were there, in part, because they liked his music. But at the end of the day, he kind of exhausted everybody.

I think about that show he did in Paris in 2022, the one you and I went to. It was very impromptu, and there was that feeling — I’m sure you remember this too — that we just had to go. We went to this modernist space that was near the Étoile, and we waited and waited, and when it started, he went on a long rant. And in the end, we didn’t see very much. I was finished at that point. I just thought, I’ve been there, I’ve seen it.

LP: Moving ahead a few years: In your 2017 column on Phoebe Philo, former creative director of Chloé and Celine, written around when she announced she was leaving Celine, you discussed how Phoebe was a deity in minimalism long before the Olsens at The Row. You recently said you felt like that piece was the first time you’d said something substantial and sensible about Phoebe, which I was very surprised by. What is it about her that has been difficult to pin down?

CH: We were summing up Phoebe’s impact at Celine because she had been there about ten years and was leaving. One of the delights and frustrations of writing about Phoebe’s shows for Celine was that you couldn’t really put your finger on what made the show so electric or on what she was trying to say about women. And I didn’t want to repeat myself from season to season, but I always felt there was something so mysterious or vague or personal about what she was doing. And, of course, that is the essence of interesting fashion — that it’s mysterious and it keeps redefining itself.

That’s what Phoebe was so good at and continues to be good at. So when she left Celine, I was able to pause and think about why she was so elusive as a subject. Maybe my favorite show to look back on was spring 2013. The venue was a grand apartment in Paris, near the Étoile — not her usual show space. It was the season that she did the Birkenstock-style sandal lined with fur. And she did a fur pump and really great raw-edged tops that were knotted in the front. And I kept thinking, Oh my God, this is such a trip. I feel like I’m on the coast of California, Big Sur or someplace. There are a few designers who are able to release your own imagination and give you the freedom to imagine whatever you want to see. And I think that dreamy part of what she does is really great.

LP: Phoebe is now at her own brand, Phoebe Philo. And I remember the reaction to her first collection, in October 2023, was very polarized — a lot of people especially had a lot of feelings around the pricing being so expensive, and there were generally a lot of high hopes around Phoebe post-Celine. How did you understand that response?

CH: With Phoebe, the pricing thing surprised me because her prices are about where everybody else’s prices are in terms of high-end fashion. In some cases, they’re a little bit lower. I think the Phoebe Philo label is a work in progress, but the key thing is she has an image of a real woman in mind. She makes clothes that are not just showpieces and that are based on the notion of a wardrobe. Since she launched her label, we’ve seen her add more separates; it all works together. I wish more designers had that — a real and specific sense of how they want a woman to dress in 2025. Sarah Burton, now at Givenchy, is also really smart and sensitive about what’s going on in the world and what women want to wear. And we don’t have enough of that.

Phoebe’s clothes also just don’t look like anybody else’s. And that’s partly why so many other designers were influenced by her in the Celine years. You look at current popular ad campaigns like H&M’s and you can see her influence again. Everyone is doing a high-collared cargo jacket or a trench or a mock turtleneck with wide trousers. Her cropped leather bomber has been copied.

LP: I remember very clearly your 2018 reviews of Raf Simons’s shows for Calvin Klein before he left in December of that year: The house had always struggled with having a clear point of view at New York Fashion Week, and that came to a head in a revealing way under Raf, in part because he was so creative. I’m curious about your perspective on the legacy of Calvin Klein now, especially with its return to NYFW in February for the first time in years, with Veronica Leoni as the new creative lead. She’s the first named designer for Calvin Klein in six years and the first woman to head the house.

CH: I started going to Raf’s shows in 1999, and I was really perplexed by them — or, I should say, in awe, though it was years before I talked to him. In July 2004, at the Paris men’s shows, he did this amazing show using a pair of escalators in a public building. And he had just won the Swiss Textiles Award, so he had some money. To me, the collection was a believable look at what fashion could be in the future, with well-polished street clothes in novel, mostly sleek white or gray fabrics, and his distinctive tailoring but now done with more finesse.

I remember Richard Buckley, who had covered menswear for years and was also Tom Ford’s late husband, saying to me, “Go back and look at Raf’s early tapes.” He meant the years 1995 to 1999. And I did that and it was a great lesson in seeing the development of someone’s career. You can come to a subject quite late and kind of miss things and then you’re not as informed as you should be. So that’s what I did, and it really changed my thinking about what Raf was about.

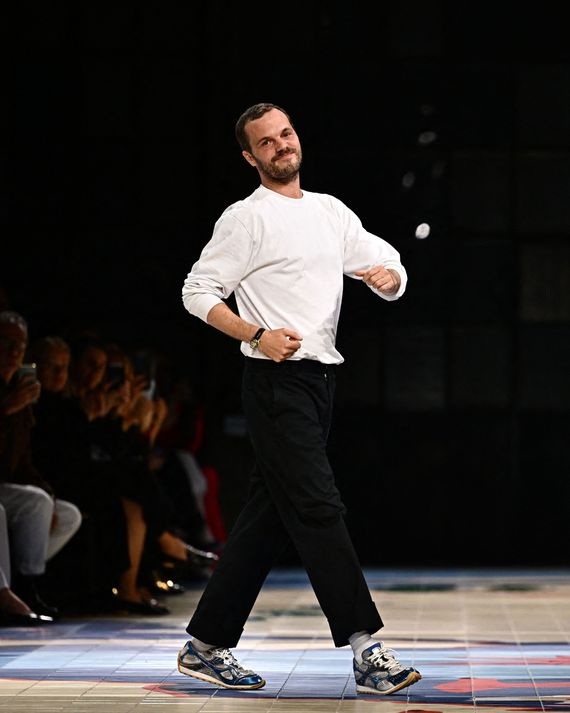

His Calvin debut was exciting. He had Pieter Mulier, now at Alaïa, and Matthieu Blazy, the new artistic director at Chanel, with him. It was a lot of change very quickly — maybe too much. I’m really looking forward to Veronica Leoni’s first collection. She’s worked for some good labels like The Row and Jil Sander, and she’s done her own brand, Quira. Her style is minimalism, but that can be interpreted in fresh ways. New York fashion needs a strong new voice.

LP: Another major focal point in a lot of your work is the avant-garde approach at Maison Margiela and by its founder, Martin Margiela. I’m curious how you all met, since Martin is known for his reclusiveness and left the brand in 2009. It’s since been led by John Galliano and, more recently, Glenn Martens.

CH: Meeting Martin in May 2018 was one of the top-five experiences in my career. I had started covering his shows around 1990. I was there for the show he held in a Salvation Army store in Paris, where he showed clear plastic bags — the kind used in a garment factory — as layered dresses. Martin never talked to the press, nor was he photographed. He was essentially anonymous. There were no show notes to explain a collection; there was nothing. You had to look at the clothes and figure it out for yourself, and there was a novelty in that. Nobody did things like that. Other designers were always accessible, and there was always a deluge of information about the collection, much of it kind of bullshitty. Martin had a very natural way of just saying, “Look at the work and judge it for yourself. I don’t need to be the focus of attention.” And whether or not you think that’s calculated, it worked well for him. And I think it also worked well for journalists: You have to use your imagination, and you have to be good at seeing.

About a year or so after the Margiela retrospective at the Palais Galliera in Paris, I asked someone at the museum if they could arrange a meeting for me with Margiela. And Martin agreed. We met one morning in a café. Nobody else was there. I kind of knew what he looked like. Anyway, I was standing there in front of the bar, and before I could say anything, he said, “I just want to thank you for all the things you’ve written about me.”

LP: Oh, wow.

CH: Nobody ever says things like that, or not often. It was kind of disconcerting because even though reporters didn’t have access to him, he was reading what we wrote about him. It was a wonderful conversation that morning.

LP: You’ve watched the evolution of Maison Margiela, and you were there in person for John Galliano’s Margiela couture show in Paris in January 2024. I, like many people, was watching on social media. So many younger people seemed to become aware of Galliano for the first time because of that show. What was that experience like?

CH: I started covering John’s collections in London in 1987, when the fashion scene there was really hot. I was at the Detroit News, reporting on fashion for the first time, and there were many exciting collections in London then: John, Vivienne Westwood, Rifat Ozbek, BodyMap. I followed John’s career when he had no money and he was struggling.

The Margiela couture show was on a cold, damp night, and it was in one of these weird caverns that are under the bridges in Paris — in this case, on the Left Bank side of the Pont Alexandre. It was like a large stone vault off the quai, partially underground. They had a big movie light set up out on the quai that created, intentionally, a kind of wet, shimmery look, like a scene in a 1930s photograph. Inside, there was a fake bar, as if we were in a typical Parisian café, and it was covered with dirty dishes and bottles turned over and ashtrays and all the crap you get at the end of the night. So you knew, metaphorically, it’s 3 a.m. and we were the lingerers. And it was all open seating, grab a table. They had glasses on the tables with little bouquets of violets. Waiters were taking drink orders. It was really casual and friendly. I remember feeling like, I’m at home. And I think a lot of people felt that.

I was sitting next to Tim Blanks, the writer, and I saw this guy swagger in. He looked like Freddie Mercury. He had a coat thrown over his shoulders, and you could see he was bare-chested. And I said to Tim, “Oh, look, one of John’s people.” He seemed like the kind of character John would imagine. And then the show started, and the guy got up and walked to the stage. He was the singer who opened the show. And then the models, girls and guys, started coming out, and we were transported to this other place. John’s imagination really was in full bloom. And it’s funny because people online started to say, “Oh, John’s back.” And I was like, “This isn’t the Galliano of the past.” John never was so body-conscious before, with the corsets and filmy dresses and the merkins. That sort of zeroing in on the body and those sort of extreme shapes was all new for John.

I loved that show because people kept talking about it for days and days. And also about the choreography and Pat McGrath’s makeup. Pat ended up giving tutorials on the glass-skin effect she’d created for the show, and people were fascinated. We all know that these shows are the result of collaborations, but that was a really good example of how it works. Weeks later, during the ready-to-wear shows, John did an amazing exhibition where he showed how the clothes were made. There was a pair of men’s pants in the collection that I really loved that had a regimental stripe on the side. I assumed the pants were made in wool, but it was actually three different materials layered together.

LP: There’s a lot of musical chairs in fashion right now. There’s always constant movement. I’m wearing Proenza Schouler today, but the brand’s founders, Jack McCollough and Lazaro Hernandez, recently stepped down. You and I have had a lot of conversations asking, “Is all this movement going forward? Is it progress?”

At the same time, designers have shifted from a more traditional hands-on role to somewhat more removed creative directors who want freedom to explore other creative pursuits. How has all of this affected the industry? What do you think about so many different major luxury brands starting with a new designer at the same time?

CH: I think it’s a great thing. I don’t know if the movement is unique to our time; we just happen to have a lot at the moment. So we’ve got Blazy arriving at Chanel. Burton at Givenchy. Leoni, who’s going to be very interesting, at Calvin Klein. Michael Rider at Celine. Louise Trotter at Bottega Veneta. We don’t know what Hedi Slimane might do now that he’s left Celine or Galliano, who’s left Margiela. We’ve got Jack and Lazaro from Proenza, as you mentioned — they’re going to be floating around, possibly going to Loewe. And Jonathan Anderson; there’s been rumors that he will land somewhere new. And he should because he’s done a lot at Loewe. He’s really raised its profile, made it interesting.

The creative-director role has evolved a lot as brands have become much bigger. When Karl Lagerfeld was at Chanel, he designed virtually everything — he did all the sketches for the clothing, and that’s the way he worked. But now Chanel is almost a $20 billion business. Louis Vuitton is a bit bigger. Dior is somewhere around maybe $9 billion. They’re machines, and the creative-director role becomes a different ball game when revenues get above $5 billion and you also have to produce several big shows a year.

Not a lot of people coming up are prepared for those jobs, or even want them, because it’s so much responsibility, and you’re not quite as hands-on as that generation of the ’90s — you think of Alexander McQueen coming up and Helmut Lang and Margiela. Or Simons, with his own brand, and Miuccia Prada. So you have to kind of train people to become creative directors, and maybe that’s just through the working process. But I think it’s good for the industry, actually. People used to admire Lagerfeld for being able to oversee three different brands and sometimes four. But nobody would do that today. It’s not something to be admired because you just humanly can’t do it.

One of the things that I’m excited about with Blazy, who will have his first collection in the fall of 2025, is that it does mean we get to finally end the Lagerfeld era at Chanel. And I loved Karl — there was no one who was more fun to talk to. And I learned a lot from him about many things in fashion. But 36 years is a long chapter for one person to be interpreting the work of one of the top revolutionary designers in the 20th century, Coco Chanel. So I look forward to Matthieu really starting a new chapter with that. That’s exciting. And I think it’s good that designers can have shorter careers in one place. I mean it’s not to say that if they want to spend 20 years, they shouldn’t. Maybe Matthieu will be at Chanel for that long. But I think it opens up all sorts of possibilities over the next few years.

LP: Now I have some rapid-fire questions. Some of these are spicy. What is one review that you regret or that you would do differently?

CH: I don’t regret any of them. Not at the Cut. I remember having a couple at the New York Times that I regretted. And even before that. And then I wrote about those pieces, changing my mind, like Marc Jacobs’s grunge collection.

The message there is to be open-minded. Fashion is about new. I also wrote a piece on Stefano Pilati when he was at his first collection for Saint Laurent. I rethought that whole thing.

LP: What is your favorite thing to plant at your farm?

CH: Zinnia seeds after the first frost. I plant, I don’t know, something like 1,500 seeds in the ground. And I do about the same with sunflowers, maybe a thousand sunflowers.

It’s a small production. We’re very small. That’s nothing. Right now, we’ve had such a cold winter. I overwintered my dahlias, and I’m worried they might not make it. So I might be planting new dahlias this spring.

LP: What has it been like to have designers respond publicly? I think about Oscar de la Renta taking out the open letter in WWD; I think of Hedi and his mock newspaper on Twitter.

CH: I remember being in my hotel room in Paris. I was on deadline when I got a call from Women’s Wear Daily. That Hedi had — and I knew Hedi pretty well before that, but he and I had a falling-out. And I remember the reporter asking me, and I was on deadline. And I was like, “Oh, that’s silly.” And I went off; I didn’t even think about it because I had to get back to writing the review, whatever I was writing that night. I didn’t think about it too much.

The whole Oscar thing was interesting, because again, everything is context. Oscar and I were still friends, even though he took that ad out. He misunderstood what I was saying, first of all. But I have a picture on my phone, taken about six months later. I went over to see Oscar in his office. I used to pay a house call; before the shows, I’d go see different designers, and I would see Oscar. And he’d say, “But Cathy, we got a lot of publicity out of it.” That’s how he was. He was a very competitive guy. And I remember when I was working with Bill Blass on his memoir, I think Oscar was kvetchy about that, because I was spending so much time with Bill, and they were very competitive. It was something that John Fairchild understood about those guys from that generation, of the ’60s. And he knew how to play one off the other. And he would do it with socialites, and other people that were part of W and Women’s Wear Daily.

So I took it all in stride, and I was more amused or baffled by it that people would get public about it. But the one thing that I always thought was strange, though, is that designers have been banning the press for a long time. Balenciaga did it in the 1950s, and there might’ve been people before that. I remember when Armani banned me for something. It was something the internet had started. I mean … You could see the clothes online. So I didn’t understand what the point of being banned was. It was more of a personal thing with them; it was like an old-school thing. I wasn’t invited when Hedi was at Saint Laurent, but it didn’t matter because you could see everything online. So that cudgel didn’t make a difference. It’s part of the job.

LP: Okay, last question, because we spend so much time in cars: We’re all working, on calls, trying to figure out how to get out of traffic, rushing. What is your favorite snack to eat in the car?

CH: Oh my God. We have so much fun in the car. We have the Milan car, Franco, who supplies us with candy. But he’s also very good at taking us to bakeries, too. We can just say, “You know, that pizza place, Franco. Over near Corso Como,” and he knows what we’re talking about. Princi. And we have different drivers in Paris. But I don’t think we have enough snacks in the car, actually. We need to improve our snacks. We always have some cookies, and we have some candy, usually. But I think we need to upgrade. We need to make more of an effort on the snacks.

More From the 2025 Spring Fashion Issue

- Good Hair Starts in the Shower

- A ‘Bright Spot’ in Washington

- 7 Tips for Making Your Outfit More Interesting