More than 1,600 sexual assault cases against Uber merged in far-reaching court ruling

- Share via

- Uber said the fine print of its user agreement blocked the government from consolidating riders’ civil suits.

- The 9th Circuit Court of Appeals disagreed, allowing the more than 1,600 cases to continue in San Francisco before a single judge.

- The precedent-setting case limits how apps indemnify themselves against lawsuits.

The 9th Circuit Court of Appeals has ruled that more than 1,600 sexual assault cases against Uber will be allowed to continue before a single San Francisco judge, a move with far-reaching implications for the ride-hailing app and its cohort in Silicon Valley.

The decision issued Monday upholds an earlier ruling by a council of federal judges appointed to centralize civil suits from across the country.

Experts said the litigation is being followed closely by home-sharing platforms, dog-walking services and other “independent-contractor” apps, which have also been hit with stacks of sexual assault liability claims, along with Uber’s main competitor, Lyft.

Uber argued a four-year-old clause in the fine print of its user agreement barred riders from joining any mass lawsuit against the platform.

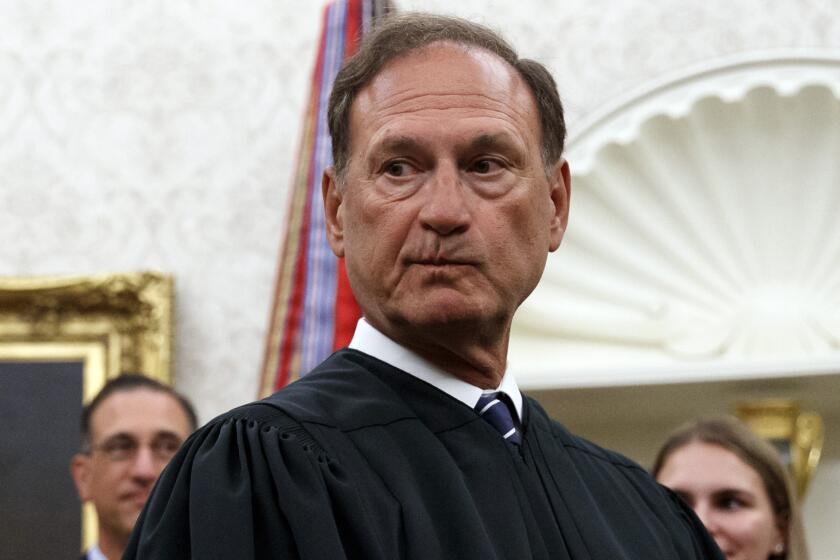

Conservative Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. lambasted the 9th Circuit Court over its decision upholding a judgment for the family of a man killed by police.

Hundreds of rape survivors claim the tech giant skimped on driver background checks, failed to report sexual violence to police and allowed sex offenders to drive for the company — all while banking millions in “rider safety fees.”

The appellate court said federal law trumps Uber’s terms of use agreement, which U.S. District Judge Charles R. Breyer of California’s Northern District had previously deemed “unenforceable.”

Judge Lucy Haeron Koh wrote in the higher court’s decision that 50 years of precedent stood against the type of reversal sought by the ride-sharing app, with not “a single instance” on the record to justify blocking what’s known as “centralization.”

“Uber has not convinced us that we should be the first,” the judge wrote.

Experts said the ruling marks a legal line in the sand for agreements app users must accept before ordering takeout, posting a thirst trap, borrowing an ebook or viewing their lab results. The lengthy waivers are unavoidable, and have become ever-more-indemnifying, experts said.

“Most people don’t even read those terms of use,” said Lindsay Nako, executive director of Impact Fund, a social justice litigation group — yet the click-to-agree contracts tightly control what happens if they’re injured.

Uber did not respond to requests for comment, but in its appeal to the 9th Circuit, the platform’s attorneys argued a “non-consolidation clause” in its terms of use was actually better for plaintiffs because it ensured each case would be heard on its own merits rather than in one clearinghouse proceeding.

Appellate court says Grindr is immune in teen-versus-tech child sex trafficking lawsuit, citing Section 230 rules

“The terms of use allow plaintiffs to have their day in court,” Uber’s lawyers wrote. “Plaintiffs simply agreed to do that individually.”

But Nako and others tracking the case said if Uber could easily unwind cases the government binds together, other big companies would write identical provisions into their own terms of use, tangling federal civil courts in endless duplicative lawsuits — making it much harder for victims to collect damages.

By blocking the clause, the experts said, the court preserved rights most users never realize they’ve been asked to give away.

“It’s a great win for consumers and a bad day for tech companies,” said Kathryn Kosmides, an advocate at Helping Survivors, a partnership between victims’ advocates and personal injury lawyers. “This latest ruling sets precedent around app safety. A lot of companies are very nervous about what happens [next] in this case.”

In one sense, the ruling is simple: By siding with survivors and the panel, the 9th Circuit affirmed the court’s right to manage its own business. Combining alike cases saves taxpayers money, helps ease court backlogs and avoids precedent-setting decisions that may be in conflict, Koh wrote in her decision.

It is also incredibly common. About 70% of federal civil action is currently adjudicated as part of a multidistrict case, Breyer estimated.

“It’s a mind-bogglingly huge number,” Nako said of the multidistrict caseload.

Advocates say arguing a single case in a single courthouse is easier and cheaper than arguing hundreds in courtrooms across the country. It’s also good for plaintiffs, who largely seek the same sets of documents from the companies they sue.

Consolidated litigation can make it easier for plaintiffs to prove the wrongdoings they allege are systemic, experts said. Companies that lose or settle such cases are more likely to have to change how they operate, rather than simply paying out.

Johnson & Johnson stopped using talc in its baby powder in 2023, following a multidistrict case that unearthed records showing the company knew its ingredient tested positive for asbestos, a carcinogen, for half a century. The company says its baby powder has always been safe and doesn’t cause cancer.

The 9th Circuit is no longer the venue of choice for challenges to Donald Trump’s agenda — in large part due to his first-term efforts to remake a court he called ‘disgraceful.’

A consolidated suit against Oxycontin-maker Purdue, widely considered the engine of the opioid crisis, resulted in the largest award for damages in American history.

In Uber’s case, a loss could mean having to beef up background checks, tighten rules around who can contract to pick up passengers, drop drivers reported for misconduct, and install cameras to record every ride, among other changes.

Such changes would be expensive and potentially unpopular. But they aren’t the only outcome the ride-hailing app is trying to avoid.

Centralized cases can unearth huge troves of evidence that would never otherwise be part of the public record. Uber has been fighting for months to avoid discovery in California’s Northern District while the appellate court weighed whether the case could stay there.

“Does Uber want this data they had about sexual assaults becoming public? Hell no!” Kosmides said.

Now that the 9th Circuit has rejected its appeal, “there is no incentive to take this through discovery and to a courtroom with a jury, because ultimately in civil litigation, discovery becomes public,” she said.

“I think we will see more of those being pursued,” Kosmides said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.