In the days when your phone was a BlackBerry and Kylie and Kendall were barely in kindergarten, I was something of a somebody on the New York social scene.

The mid-aughts were a busy time for fashion publicists like me. It was the heyday of the brand extension, the licensed-product category, the corporate investment, the megashow. One of the most efficient ways we set this cycle in motion then was to go to — or throw — a party where you’d mingle with A-listers, meet potential clients, and get your picture taken to help more people recognize you. It wasn’t that hard to pull off, especially since the fashion sites that were springing up everywhere needed things to cover in between show seasons — “content.”

Cover Story

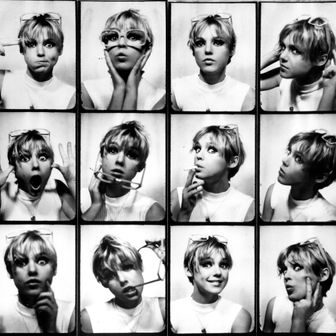

The women who had been photographed at events in the decades before were usually clients who owned the clothes that they wore. But the new crop of party guests — known as socials, never “socialites” — borrowed. Though they weren’t necessarily rich, they were nearly always rich-adjacent — a fancy last name, a loaded boyfriend — as well as pretty, polished, sample size, and usually anointed by the hidden hand of Vogue. And thanks to my Waspy upbringing in San Francisco’s Pacific Heights plus four years at Brown, I already knew some of these women personally or generally. I’d begin to meet the rest as they came to select dresses from the showroom, or I sent them invitations and gifts on behalf of clients. When we saw one another at benefits that brands would underwrite or designers would co-chair, at the cocktail receptions and launch dinners and after-parties that seemed to happen nightly, we’d double kiss and talk animatedly — perfect for a candid photo. In these target-rich environments, the hunky Patrick McMullan photographers commissioned by style.com and Fashion Week Daily and New York Social Diary snapped away, arranging groups of two and three to pose and smile wide for the camera, which people still did then. Occasionally, I’d be coaxed into posing too. I never expected the pictures to appear beyond Patrick’s website, but one day, a photo of me was posted — I don’t even remember where. That one led to others, which would ultimately spawn party-committee solicitations, invitations to openings, and, ironically, fashion shows. Thus I began a new, parallel existence: as a social. It might be hyperbolic (and certainly grandiose) to say that we were to New York what “Young Hollywood” was to L.A., but believe me when I tell you that we were as visible as noncelebrities in a pre-social-media, pre-YouTube world had a right to be.

New York’s society scene had been so white for so long that anyone would have been forgiven for thinking that might just be the point. Now, there were at least four Black socials all at once: Genevieve Jones, Maggie Betts, Shala Monroque, and me. (Note: I would be mistaken for every single one of these women at least once — one time in print.) One outlet that attempted to chronicle this period was a blog called Mocha Socialite, which featured “stories about prominent persons of African descent” and one day saw fit to profile me. The post elicited a handful of emails and even letters sent to me by mail, mostly from HBCU students who sweetly asked for my tips on how I’d been able to score the job and the affirmation. I shared advice I thought might serve them in job interviews (“Buy a pair of good heels on sale and an inexpensive black cashmere turtleneck! Think of questions to ask the person you’re meeting ahead of time! Believe in yourself!”). However, I struggled to put into words that this world was far less integrated than it appeared in pictures and that my transit through it was linked to private schools, the “right” friends, and enough parental subsidy to write checks for all those junior-committee tickets and for me to spend the rest on clothes and going out every night. As much as I wanted to stoke their enthusiasm, I was at a loss to offer anything truly meaningful. Soon, I began to deflate when these cards were dropped on my desk at work, opting to stash them under a mountain of magazines while I prayed for the hour I’d feel hopeful enough to read them.

Over time, I began to realize that even though this scene had welcomed me, it did not automatically offer me the same long-range plan that it did my peers. The most common goal (and expectation) of women I knew was to marry, and in that set, the way to really keep the fun going was to marry well. But I had found that while the social mores of turn-of-the-century jeunesse dorée had become more inclusive, their romantic bylaws lagged significantly behind. I listened meekly every time the women and gay men we knew presented everyone but me with setups. To the straight guys in our circle — scratch golfers and racquet-sport aces who might boast that they never failed to donate to the boarding schools they’d attended — I played sympathetic ear to their relationship woes or casual (if repeated, and drunken) hookup, never more. It dawned on me that everyone in my crowd was shrewdly calculating how to collect the prizes required to advance to the next rung or fretting desperately about being left behind.

Right as I was careering toward becoming the latter, I was offered a job as “special projects editor” at Men’s Vogue. The position was described to me as a combination of fashion editor, brand ambassador, networker, and event planner. On top of it all, a friend prophesied, “You’ll definitely meet a guy.” Ironically, it was almost a professional version of what prominent wives did, just with a W-2 instead of a prenup and a diamond ring. Of course I said “yes.” But by the fall, I was sitting in a meeting at MoMA to discuss a party we were sponsoring when Gawker announced that ten blocks south, my colleagues had filed into a conference room to hear Condé Nast was shutting us down. It was over.

What this meant to my social life appeared murky at first but came into sharp focus when a former dear friend and ally became less available and often even hostile, abandoning me or avoiding me at events or cutting me down in front of others. Shattering as it was, it was a radically honest confirmation of what I could no longer deny: I had lost my juice. A mutual friend attempted to help me strategize how to save the friendship. “It even happens to me when someone more fabulous is around,” she told me. “Don’t take it personally.” I admired her steely pragmatism but recalled the wisdom I had acquired observing desperate, would-be patrons cajole or rage to gain admission to the clubs where I dropped ropes every night: Never, ever beg to be let inside.

Flash-forward to last fall and an invitation arrives: The very same mutual friend is hosting a dinner on the Upper East Side. Now that race was all white people talked about, I had experienced the slightest uptick in requests for my presence. I decided to go and ended up having a lovely time. The former friend was there, greeting me warmly after years of stonewalling. I accepted the gesture, but I did not feel vindication or crave rapprochement. Despite how these women might have been portrayed at the time (snubs and sharp elbows at galas! Hand-wringing and scheming about Socialite Rank!), most in this set were nice people — not catty, disloyal, or status obsessed. But a few were, and maybe my expulsion had been for the best. While I had faded away slightly before my time, here’s what the best partygoers know: It’s better to leave early than stay too long. Since it was approaching ten o’clock, I said my good-byes and thank-yous and made my exit, heading downtown, away from the classic sixes in white-glove buildings, back to the part of the city where I still lived but we all used to play in.

More on the New York ‘It’ Girl

- ‘It’ Girls in Conversation: Anaa Saber, Maria Al-sadek, and Friends

- Today’s ‘It’ Girls in Conversation: Imani Randolph & Friends

- ‘It’ Girls in Conversation: Ivy Getty and Friends