I have fond memories of attending the Ebony Fashion Fair show as a child with my mother. We would get all dressed-up, I’d put on my socks with the frills and the fur coat my grandmother gave me. It was my first introduction to fashion and culture through a black lens — all black models, black designers, black makeup artists, and black hairstylists. I sat there wide-eyed, loving every minute.

At the time, I didn’t know that Ebony’s director, Eunice W. Johnson, was a pioneer for fashion and black designers, taking the show worldwide to demonstrate that people of color were not only innovative but deserved stage recognition, and were interested in haute couture pieces just as much as any other race.

More than a decade later, there’s finally a museum exhibition showcasing the talents of black designers in the fashion world and giving credit where it’s due to designers who have shaped the culture of the industry but received little to no recognition. There have been exhibitions about individual designers, including Stephen Burrows, who’s credited as being the first black designer to have his own high-fashion clientele, which included Barbra Streisand and Michelle Obama, and Patrick Kelly, who was the first African-American member of the Chambre Syndicale du Prêt-à-Porter (the governing body of the prestigious French ready-to-wear industry). Yet those names aren’t in the immediate vocabulary of the fashion set, which is why the Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology’s “Black Fashion Designers” is extremely necessary.

Featuring more than 60 designers, the exhibition includes 75 pieces created over the last 70 years. Not only are beautiful clothes on display, but the exhibit is also a lesson in what black designers have had to deal with in order to survive in the industry. Too often, black designers are categorized by their race — in reviews, roundups, or the stores they’re sold in. Using the word black in a review, or including a designer in a Black History Month piece, tells you only about his or her race and nothing about the actual body of work. White designers are considered the majority, while many designers of color who are not black can freely use their race as inspiration (Prabal Gurung, 3.1 Phillip Lim) without being defined by it. The fact is, black designers, specifically, are not recognized on par with their peers.

Looking at fashion and the way race has played an undeniable role in it means admitting that black designers have been limited, despite their astounding accomplishments. I wanted to hear firsthand from an insider about why black designers have been ignored, so I called on Tracy Reese, one of the few black designers who has been able to sustain a business. She says, “Most of our businesses have been undercapitalized and have failed to achieve lasting national and international distribution. It really comes down to finance. Designers need adequate capitalization to create and sustain a healthy business. It’s no secret.”

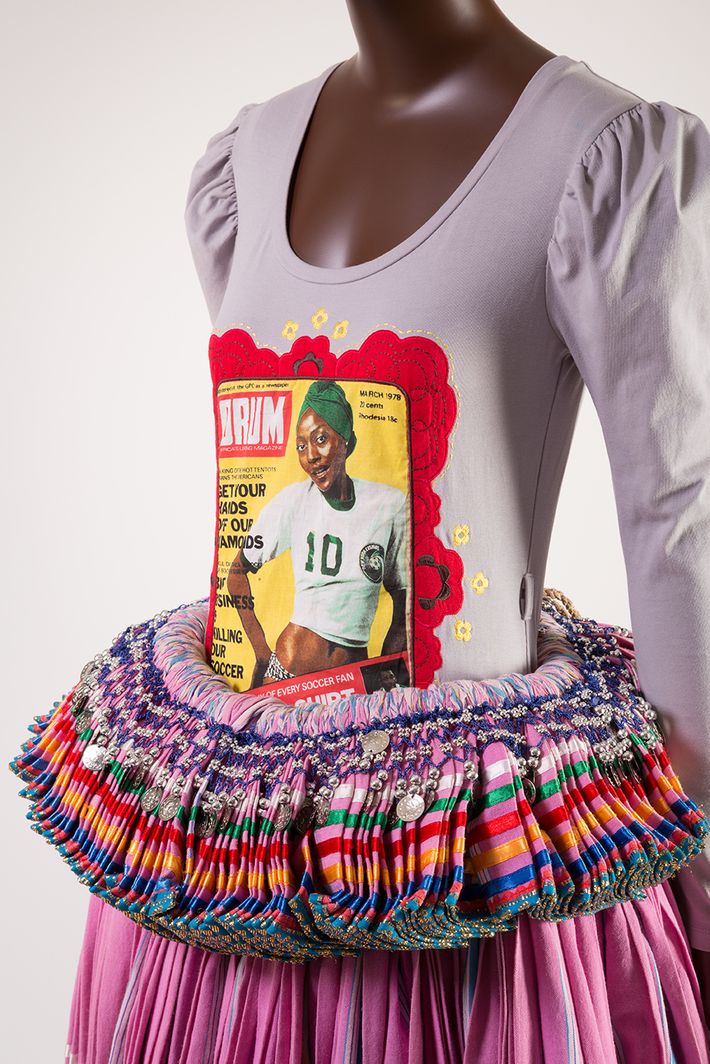

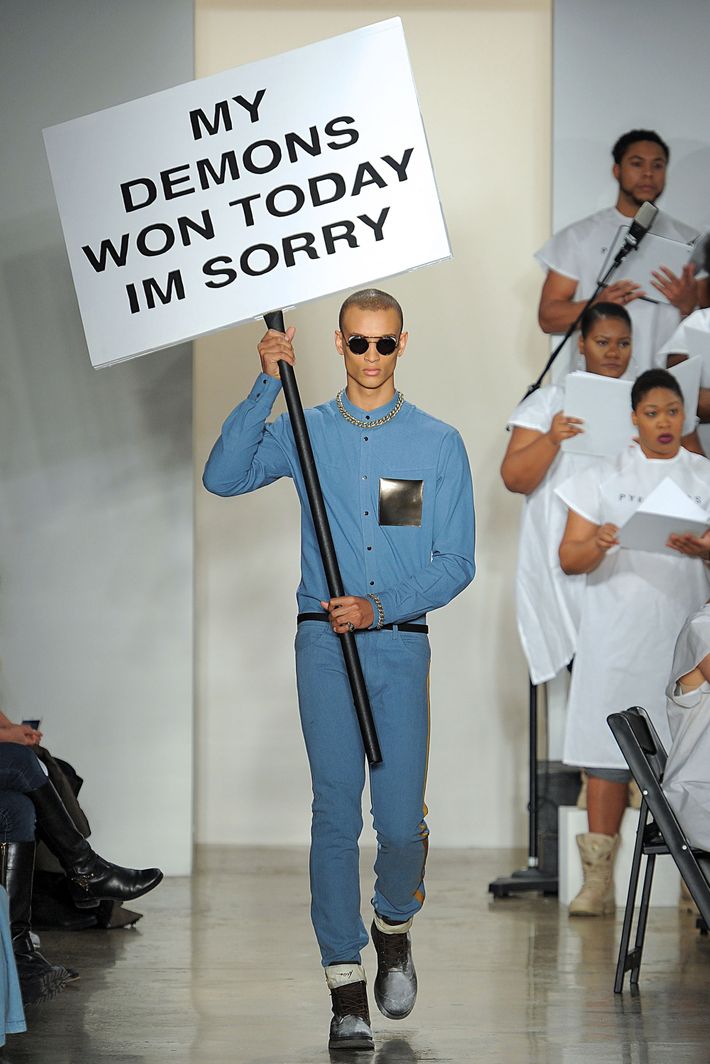

Reese is included in the exhibition, which showcases both menswear and womenswear, with sections devoted to celebrities, politics, street style, and iconic black models. Showing a wide range of black designers is also a significant part of this exhibition — from recognizable names like Reese, Pyer Moss, Public School, and Duro Olowu to lesser-known but equally influential players like Eric Gaskins (who trained under Hubert de Givenchy), Nkhensani Nkosi, Zelda Wynn Valdes, and Ann Lowe (who designed Jackie Kennedy’s wedding dress).

Though the exhibition finally gives black designers a chance to be seen, it’s disappointing that their work is only being praised in the context of other black designers and not across the fashion world as a whole. Reese shared her sentiments about the title, “Black Fashion Designers,” saying, “I prefer to be classified as a designer. My race is not central to my design aesthetic and my goal is to dress women of all races.”

The Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology’s “Black Fashion Designers” is open to the public through May 16, 2017.