On Saturday, Sylville Smith, a 23-year-old armed black man, was shot and killed by a police officer after he pulled away during a traffic stop. Protests turned into riots over the weekend. On Monday, the city declared a 10 p.m. curfew for teens. Police chief David Clarke, who has criticized Black Lives Matter and become something of a darling to the alt-right, said that people slamming cops have it wrong. “Stop trying to fix the police,” he said, “fix the ghetto.”

To Clarke, who is African-American, the unrest is evidence of “black cultural dysfunction.” Yet his city is the foremost case study in one of the United States’ gravest societal ills: segregation. Whether it’s across ethnicities or just between whites and blacks, analyses find that Milwaukee is the most segregated city in the country. Part of that is due to the Wisconsin city’s unique history: Long a town made up of distinct cloisters of Poles, Germans, and Jews, it missed out on many black transplants during the Great Migration; many more settled a hundred miles south, in Chicago. Blacks didn’t really start arriving in Milwaukee until the 1960s, when the city was already going the way of the Rust Belt. For locals, there’s an old joke that the 16th Street Viaduct, which connected the traditionally black and white communities, was the longest bridge in the world, since going over it meant going from “Africa and Poland.”

Across the U.S., the cities with the greatest geographic segregation tend to have the highest rates of violence. Among cities with over 250,000 people, the FBI says that Detroit has the highest violent-crime rate, followed by Memphis, Oakland, St. Louis, and Milwaukee. According to analysis of the latest census, Milwaukee is the most segregated city, followed by Detroit, Cleveland, New York City, Buffalo, and St. Louis coming in sixth. That’s a strong correlation, and from what sociologists say, there’s a lot of causation.

“With isolation, poverty, and political impotence on top of each other, that produces a series of cultural responses that can, in a variety of ways, intensify people’s economic hardship and can also contribute to criminality and gang formation,” says Brooklyn College sociologist Alex Vitale, noting that the same doesn’t carry over for wealthy people living in geographically isolated communities that are nonetheless connected with education, transportation, and other resources. “In Milwaukee, you have entrenched physical segregation but also enforced social segregation, so these folks are cut off from all kinds of institutions.”

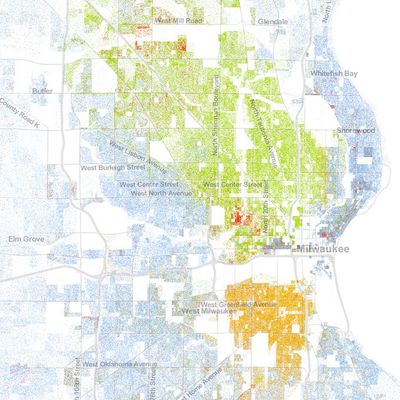

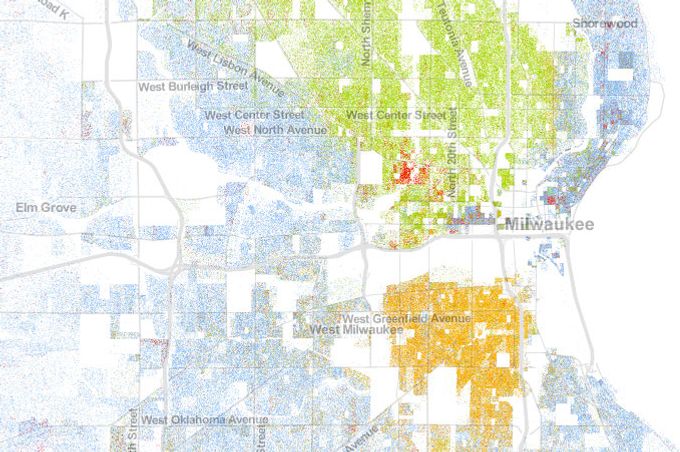

This is what Milwaukee looks like today, according to the 2010 Census, as visualized by the University of Virginia’s Racial Dot Map:

Green dots represent black people, blue represent whites, yellow represent Hispanics, and red represent Asian, with brown as a catchall for everybody else. Today, very few whites live within Milwaukee proper; they’re in the suburbs. Coincidentally, that’s where Donald Trump went this week to publicly address the problems within inner cities.

Milwaukee’s geographic segregation is coupled with further structural disadvantage. As Kenya Downs reported for NPR, over 50 percent of black men in their 30s and 40s have been incarcerated in Milwaukee County, and Milwaukee has the most black students in a state with the biggest achievement gap between black and white students in the country. It has also seen a huge uptick, contra to Clarke’s claims, in cops’ use of force: The Milwaukee Police Department saw a 200 percent increase in police shootings from 2014 to 2015.

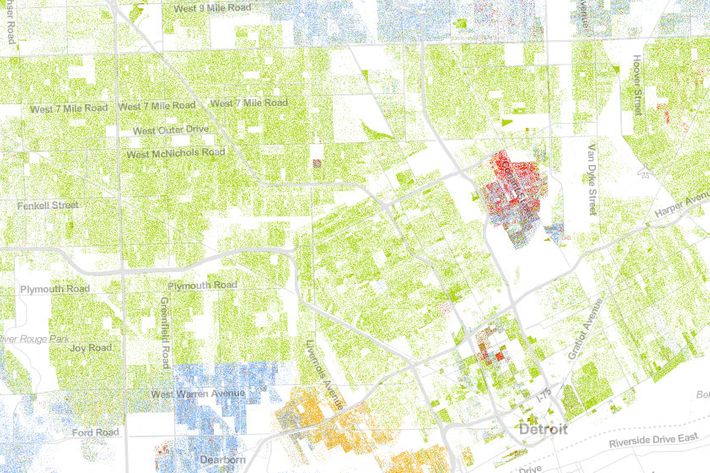

Add all this up and you get what sociologists call Neighborhood-Level Effect, where the neighborhood you live in is predictive of how your life takes shape. An initiative in Philadelphia where young mothers were given housing for committing to public education provides a recently analyzed case study. When the moms were placed in low-poverty neighborhoods, they earned more college credits compared to the control group living in high-poverty neighborhoods. In these isolated parts of Milwaukee — or Chicago or Baltimore — young people have to “have to adopt protective behaviors to survive daily life,” Vitale says, like traveling in groups, being prepared to use violence, and fitting into street culture. Yet those same behaviors make it harder to be successful at school or to enter the labor force. Add in intensive policing and criminal records, and isolation increases. Detroit, the most violent big city in America, is almost perfectly divided by ethnicity by its immortalized Eight Mile Road, which forms the northern border of the city limit. Notice how the green dots — signaling black residents — end at that line, with blue dots — white folks — on the other side of the divide.

“Segregation changes people’s networks,” Yale University sociologist Andrew Papachristos tells Science of Us. He has studied Chicago, America’s seventh-most segregated city, and found that between 2006 and 2012, 70 percent of all nonfatal gunshot injuries — an index for people participating in violence — happened within a network that accounted for about 6 percent of the city’s total population. Violence travels within these relatively closed-off networks like an STI. While the isolation keeps violence inside, he says, things like access to social networks, political networks, and professional networks stay outside. If you’re segregated from transportation, it will affect employment: You can see it in how poor kids who grow up in better-connected neighborhoods have a better shot at climbing the economic ladder. If you’re in a food desert — where you’re a mile or more from the nearest grocery store — it will affect your health. “If you don’t have transportation, you’re spending all your income on shitty food from the bodega,” he says.

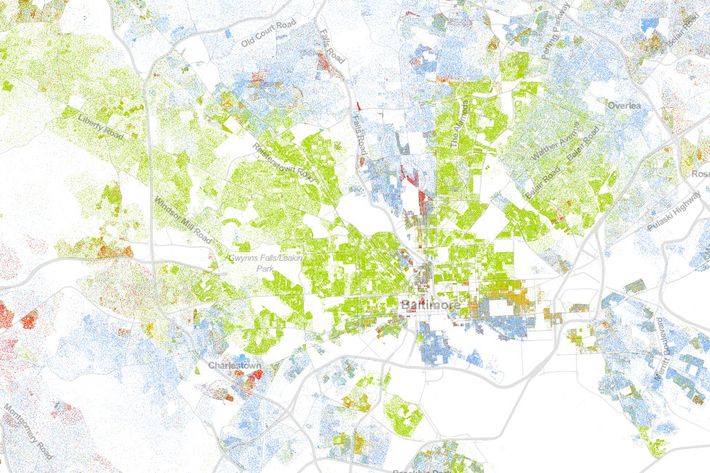

Segregation didn’t come from nowhere. In 1910, a black lawyer opened up an office in Baltimore in a house that he bought from a white woman. That same year, the Baltimore city council passed an ordinance that prohibited blacks from moving onto white residential blocks and whites to move to black blocks, as Antero Pietila records in his Not in My Neighborhood: How Bigotry Shaped a Great American City. Through the rule of law, city-wide separation of ethnicities was achieved, an “innovation” that was exported to Atlanta, St. Louis, New Orleans, and other American cities facing influxes of black migrants. Writing about the legislation last year, Matthew Yglesias quipped that after you “corral a minority group into a confined geographical space,” a city isn’t going to follow up by investing in best-in-class parks, schools, transportation, and policing to that same area.

The systemized discrimination only gathered steam with the Federal Housing Administration, who from 1934 to 1968 guaranteed home loans to white people while refusing — explicitly — to do the same for black people, or people who lived near black people. The practice is called redlining, and as Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote in 2014, it “destroyed the possibility of investment wherever black people lived.” It’s crucial to note that segregation isn’t just a historical legacy that hasn’t worked itself out yet, says Vitale, the Brooklyn College sociologist; it’s an “actively produced dynamic” that “requires constant reproduction” by real-estate owners and brokers, banks, police, and other groups. While there’s isn’t explicit, formalized redlining today like there was decades ago, there are still implicit practices. Take credit-risk assessment, for example. “You can’t get a loan, not because you’re black but because you have a low-paying job and got arrested for pot one time,” Vitale says, “and that’s because you live in a heavily policed neighborhood. No white kid in suburbia is arrested for pot, so they don’t have a pot arrest on their record.”

Getting neighborhood-level effect to change is a bewilderingly complex issue; you can’t arrest your way out if it. Most interventions have been focused on individuals. As mentioned above, you give housing to single mothers in Philadelphia in better neighborhoods and they earn 50 percent more college credits. You teach Chicago teens to become mindful of the reactions they’ve been acculturated to and violent crime falls by 44 percent. The “most lethal” young men in Richmond, California, are given stipends if they commit to not being involved in gun violence and to follow a life plan, and the city’s murder rate plummets by over 70 percent over seven years. Top-down, neighborhood-wide interventions are rare and expensive. The Harlem Children’s Zone is a notable exception: Starting on one block in the 1990s, it now covers 97 blocks in Central Harlem, serving 13,000 youth and 13,800 adults with early childhood and K–12 education, college prep, and community centers. While the program reports that it had an overall 93 percent college acceptance rate in 2015 and has kept over 1,000 families out of foster care since 2010, critics question its cost and whether the model can truly be replicated in other contexts.

It might be that the best way to end segregation — and with it, concentrated poverty and crime — is immigration. First-generation immigrants are involved in way less crime than their socioeconomic status might indicate, and their kids overachieve in school. A 2010 study found that the U.S. cities that received the most immigrants between 1990 and 2000 saw the biggest drops in violent crime. San Diego neighborhoods with more immigrants later had fewer murders; Chicago neighborhoods with more languages spoken in the 1990s saw fewer homicides in the 2000s; and and in New York, a one-percent increase in immigrants in a precinct between 1975 and 2013 predicted a 966 fewer crimes per year.

As has been shown in places like Washington, D.C., immigrants move into depressed, isolated neighborhoods, creating wealth for everybody. This leads to increased safety and perception of safety. Economic development follows, and soon enough gentrifiers and investors start coming, too. Just as segregation is the product of myriad forces, so is integration. In what may be surprising news to Mr. Trump, immigration is one of the best levers America has.