The photographer Christopher Williams, who has flown under the radar despite having been called “his generation’s leading Conceptualist,” is known for images that carefully blur the line between advertising and fine-art photography. In one of his famous pictures, there’s a woman with dirty feet in sheer lingerie fitted with clothing pins. In another, there are stacked Ritter Sport chocolate bars of different flavors, where the almonds, hazelnuts, and marzipan create layers of patterns. “There are lots of products in my work, but you don’t get the idea that the object is being sold,” Williams tells the Cut.

This weekend, Williams opened “The Production Line of Happiness,” a retrospective at MoMA that features nearly 100 works from his 35-year career. Williams, who skates between clever photographer and conceptual wizard, has hung the entire show considerably lower than the standard height. In fact, he mounted his photos about a foot below what we’re used to seeing, “unless you’re really short,” says Williams, as he cracks a smile, “but even I have to bend over to look at these.”

Williams says the whole show can be seen as “an essay on walls and pictures,” and there are some highly conceptual elements that come with such a mission. His work elicits a range of reactions, from cold to tricky — even New York’s Jerry Saltz has called Williams “a hard guy to get a purchase on.” His photographs juxtapose mundane subjects, like soap and camera equipment, against pictures of female models and curious characters, echoing the look of 1960s-era commercial photography. Often, Williams plays more of a director role in their creation, rather than manning the camera himself, by working with a team of professionals who click the shutter while he orchestrates the scenes.

“I’m actually a little puzzled when people say that I’m interested in a lack of transparency or making puzzles,” he says. “I think my work is a lot more direct than people allow it to be,” he continues. Williams, who is currently the photography chair at the Düsseldorf Kunstakademie, has a show opening in November of new photographs (he’s really into airplanes at the moment) at David Zwirner. He spoke to the Cut about the power of imaginative thinking, the universality of a shower, and even his fashion dreams.

Much has been written about the nature of your practice. What it is you think you do?

If you push two models together — conceptual art and institutional critique — you might have an idea of what I do. I think I function more as an art historian in a way, or a picture editor at a magazine, sometimes an art director, and then sometimes a traditional photographer. This kind of photography is about an intense contemplative mode on the part of the viewer. A lot has been said about me working with commercial photographers, but actually I set up a situation where I move around through different aspects of the production. It allows me a freedom to see different ways of doing things. Everything has a relationship to the conventional, but it’s all slightly akimbo in a way to hopefully make the viewer aware of it — like I make the titles too long or too short, and I hang the pictures lower than normal.

Your images look like magazine spreads, and yet they’re fine art. Where do you see the lines drawn?

A lot of the motifs and methods I use are associated with advertising, but I try to slow it down. Those are techniques used for quick consumption. I used to work on commercial shoots, and I’m not so interested in a deconstructive relationship to advertising. When I worked on an advertising shoot, I was impressed by how much information the camera got, but by the time it was on a magazine page, of course, all the details seen as imperfections had been removed. Details slow you down when [you’re] looking, but with airbrushing or Photoshop, the idea is to speed it up so your eye slides over it. I decide to leave them as a way to use the power that the camera has to register details and play with them.

Why do you think your work, or art in general, has such creative flexibility?

Artists are less accountable to the idea of “box office.” It’s changing; there’s a lot of pressure to deal with the amount of people who see a show. But I come from Los Angeles, where every Saturday morning they release how much each film has made. The art world is much less involved with that still. What the art world has to offer, that other contexts don’t, is room for speculative thought — What if? What if you put walls on the floor? What if elephants walk sideways? — and the freedom to look as long as you want. I like the idea that you can spend ten seconds, ten minutes, or ten hours looking. Although at MoMA, you can’t spend more than ten hours, except when they’re open late on Fridays.

Would you be interested in working in fashion or editorial?

Theoretically, I would be interested, and art history is filled with people working in photography who did both — Man Ray is one of the most famous, and a couple of my colleagues do, too, like Wolfgang Tillmans and Roe Ethridge. I might be wrong, but I don’t think my temperament is right for it. On a shoot, you have optical technicians, mechanical engineers, chemical agents — you have all these people working to make an image, and one could ask why is the photographer privileged? In advertising, you’re promoting a product. There are lots of products in my work, but you don’t get the idea that the object is being sold.

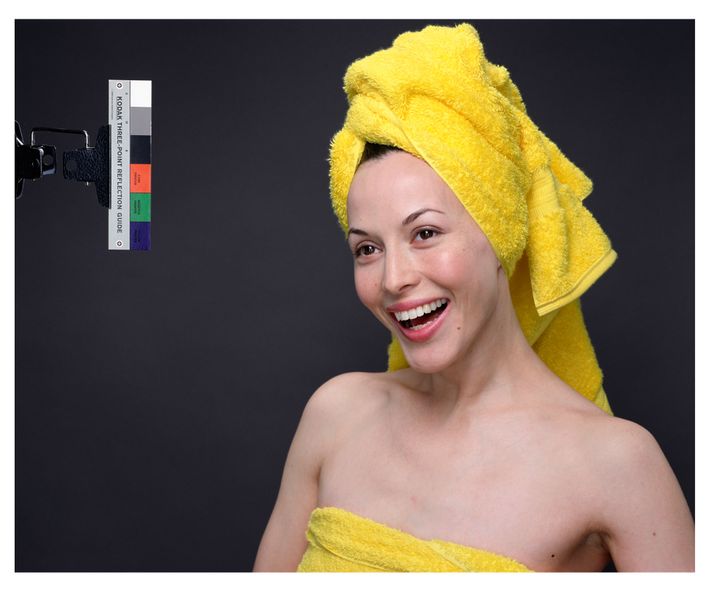

Kodak Three Point Reflection Guide / © 1968, Eastman Kodak Company, 1968 / (Meiko laughing) / Vancouver, B.C. / April 6, 2005.

Model #105M – R59C / Keystone Shower Door / 57.4 × 59˝ / Chrome/Raindrop / SKU #109149 / #96235. 970 – 084 – 000 / (Meiko) / Vancouver, B.C / April 6, 2005 (No. 1).

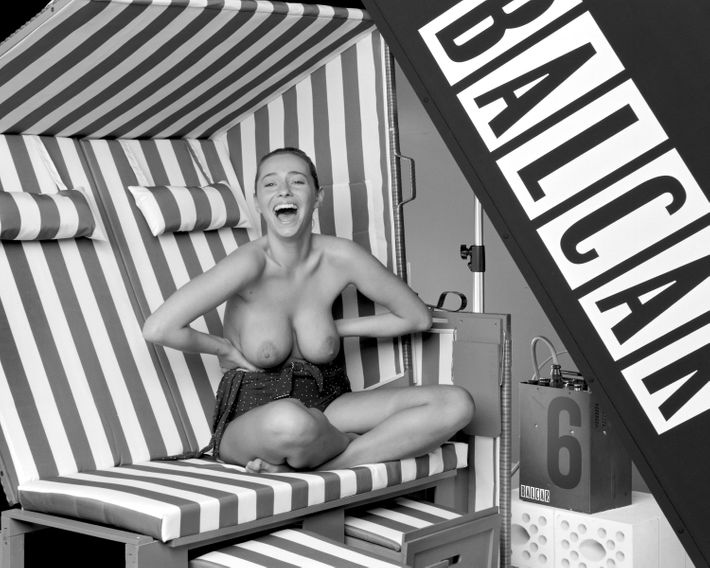

TecTake Luxus Strandkorb grau/weiß / Model no.: 400636 / Material: wood/plastic / Dimensions (height/width/depth): 154 cm × 116 cm × 77 cm / Weight: 49 kg / Manufactured by Ningbo Jin Mao Import & Export Co., Ltd, / Ningbo, Zhejiang, China for TecTake GmbH, Igersheim, Germany / Model: Zimra Geurts, Playboy Netherlands Playmate of the Year 2012 / Studio Rhein Verlag, Düsseldorf

Weimar Lux CDS, VEB Feingerätewerk Weimar / Price 86.50 Mark GDR / Filmempfindlichkeitsbereich 9 bis 45 DIN und 6 bis 25000 ASA / Blendenskala 0,5 bis 45, Zeitskala 1/4000 Sekunde bis 8 Stunden, ca. 1980 / Models: Ellena Borho and Christoph Boland / November 12, 2010.

Fig. 2: Loading the film (ORWO NP15 135-36 ASA 25, Manufactured by VEB Filmfabrik Wolfen, Wolfen, German Democratic Republic) / Exakta Varex IIa / 35 mm film SLR camera / Manufactured by Ihagee Kamerawerk Steenbergen & Co, Dresden, German Democratic Republic / Body serial no. 979625 (Production period: 1960–1963) / Carl Zeiss Jena Tessar / 50mm f/2.8 lens / Manufactured by VEB Carl Zeiss Jena, Jena, / German Democratic Republic / Serial no. 8034351 (Production period: 1967–1970) / Model: Christoph Boland / Studio Thomas Borho, Oberkasseler Str. 39, Düsseldorf, Germany

Untitled (Study in Yellow and Green/East Berlin) / Studio Thomas Borho, Oberkasseler Str. 39, Düsseldorf, Germany

RITTERSPORT / Von oben nach unten/from top to bottom / 100g Tafeln/100 g Bars / Offizieller Produktname/Official Product Name/Ean Code Bar/ / UPC Code for Case/Bars per Case / Voll Nuss/ Whole Hazelnuts/4000417019004/050255013005/10 / Joghurt/Yogurt/4004170270 09/ 0525502700/12 / Voll Erdnuss/4000417266202/…/10 / Weisse Voll Nuss/ White Whole Hazelnuts/4000417013002/ / 050255013003/10 / Marzipan/Marzipan/40041725005/050255025006/12 / Cappucino/Cappuccino/40004172300 03/0550255230042/12 / Fotostudio Axel Gnad, Düsseldorf

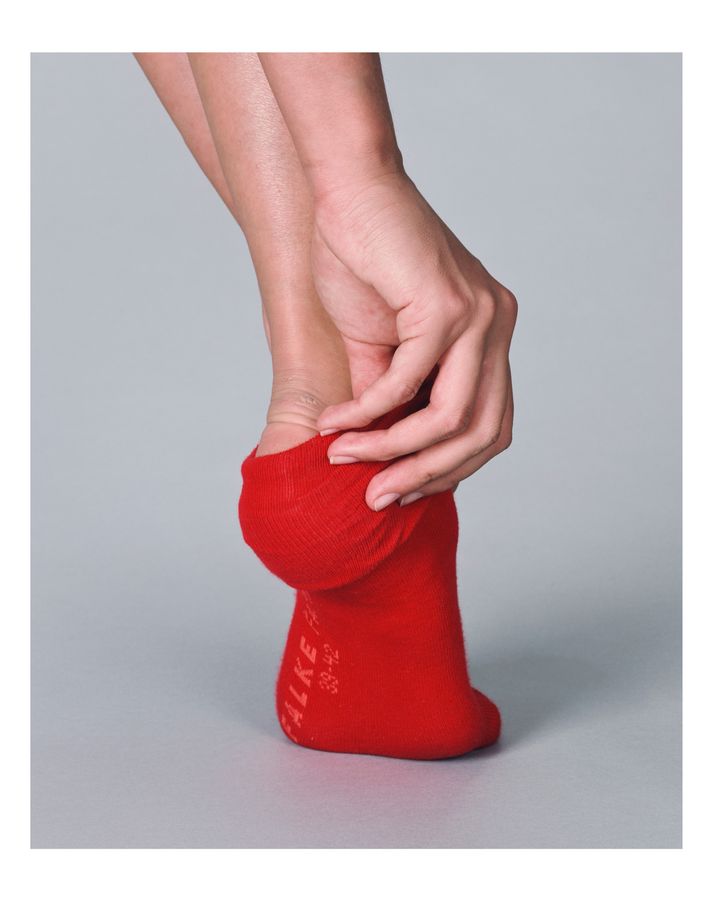

Untitled (Study in Red) / Dirk Schaper Studio, Berlin / April 30, 2009.