The Musée de la Contrefaçon — the Museum of Counterfeiting — sits inside an ornate hôtel particulier in Paris’s 16th Arrondissement. In the 1920s, it was the property of a rich American heiress but — after being damaged in World War II — became the property of Gaston-Louis Vuitton (grandson of guess who?) in 1950.

Vuitton gifted the building to UNIFAB (l’Union des Fabricants, a.k.a. the Union of Manufacturers), a French association created to protect commercial creations and intellectual property, of which he was president. Now, the building serves as its headquarters — and as Paris’s repository for legally confiscated counterfeit items that have been procured from customs, the police, and sometimes brands themselves, who recuperate forged items to learn for future prevention.

Today, the six-room museum holds over 500 pieces of counterfeit merchandise, from luxury goods to quotidian items (pens!) to forged art, collected since the museum opened in 1972. About half of its inventory is confiscated, while the other half is donated — and new items are added constantly. (In fact, a “forged object of the month” vitrine has just been instated in the museum, which currently holds a knockoff steam mop, the original of which is available for purchase on a TV network shopping channel.) The museum juxtaposes several real items next to fake ones.

While the museum says that technology and pharmaceuticals are the most-copied items on display, there’s a large section dedicated to luxury fashion and beauty knockoffs. There are silver lamé stiletto-heeled “Nike” sneakers; babouche slippers in knockoff Burberry plaid, pink rubber kitchen gloves with “Chanel” printed in white at the wrists (oddly, now less preposterous in light of the last supermarket-sweepstakes-themed collection); and endless Louis Vuitton–like monograms and fleur de lis, both in classical brown and the rainbowed monogram. There’s a showcase of fake “It” bags, each with bungled details: an imitation Chloé Paddington bag with its enormous lock, a Kelly bag manufactured in South Korea, a quilted Lady Dior bag with awkwardly sized handles and inaccurate gold trimmings. Not only are some fakes not even based on existing items, they’re a mash-up of manifold references. There are weird crossbreeds of labels, like a red cardigan with multiple brand names dotted all over, or a white Nike sneaker with the “LV” monogram in the swoosh.

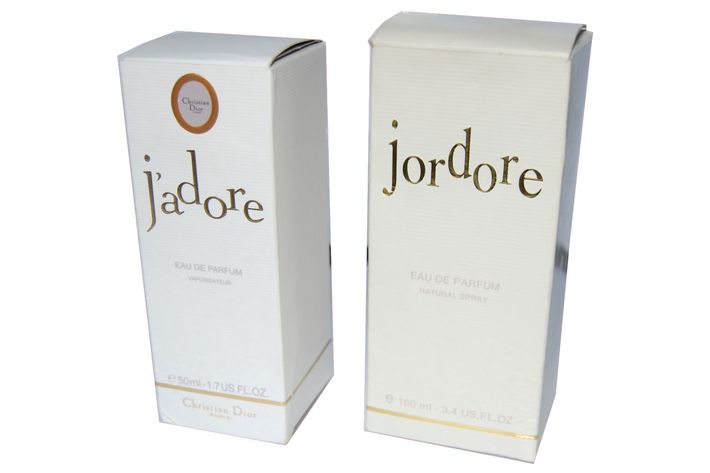

In the realm of cosmetics, there are beauty products never created or sold by brands, as well as misspelled mock-ups, like “Christen Diar.” There are faux perfumes too, whose defining ingredients have been omitted — musk, violet, mandarin. As result, the liquid changes over time, as seen with Jean Paul Gaultier’s Classique and its doppelgänger’s muddled shade.

There are more horrifying examples of counterfeiting with seriously dangerous effects: foods without preservatives, glucose placebos masquerading as medicine — even nightmarish-looking off-brand Teletubbies and dolls with tiny swallowable parts. Another recent donation was a Samsung Galaxy S telephone, recuperated via Price Minister in December 2013: The packaging is a perfect copy, but the logo is off.

According to the museum, 70 percent of forgeries originate from Southeast Asia, but also the Mediterranean (Turkey, Morocco, Tunisia) and parts of Europe (Italy, Spain, Portugal). In order to capitalize on first impressions and brand recognition, “counterfeiters spend much more time realizing the packaging than the content,” says Regis Mesali, the museum’s director of communications. Packaging is usually closely mimicked, but “there’s always a little detail that makes you realize it’s copied.”

Walking through the museum feels like stepping into a giant blooper reel of consumer and luxury culture — something that speaks significantly to our confounded sense of perceived taste and capital. Occasionally, the items come close to the real thing, but many don’t even aspire to that, evoking only a vague proximity to something recognizable. It’s wrong, yes, but it also makes us confront how faithfully we cling to that which we recognize, even if that recognition is theoretical.

In a kind of strange meta-symbolism, the building that houses the Musée de la Contrefaçon is, in itself, a copy of a 17th-century building once located in the Marais. The original was destroyed during the Haussmannian reconstruction of Paris.