This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

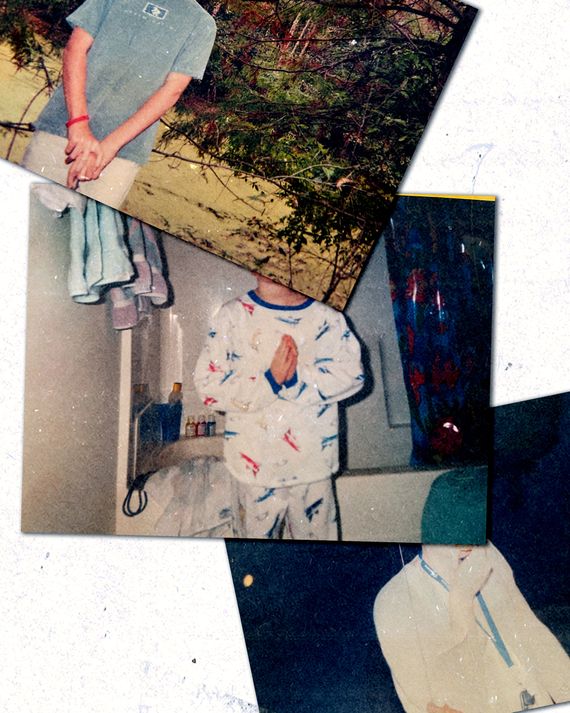

I no longer believe in salvation. But when I did, I spent hours walking around the suburbs smoking cigarettes, desperate not to acknowledge the obvious. Around the time I turned 15, my parents drove me three hours across Indiana to see a Christian psychologist. A month earlier, I had broken up with my girlfriend and my mom had turned to me in our minivan at a red light and asked me if I was gay. My silence was my confession.

My siblings stayed with my aunt and uncle as my parents and I tried to get to the bottom of my homosexual tendencies with a professional. (That I might eventually come out as transgender had not yet crossed their minds, despite the fact that I loved to play pretend as Princess Leia.) When the psychologist spoke with me alone, I resolved to give him as little as possible. I sat in defensive silence as he asked me questions about whether I’d slept with a man, if I had ever watched porn, and other intimate details about my body. I soon understood that the cost of pleasure was hell.

I often wonder what people picture when I talk about conversion therapy — if they picture anything at all. They’re probably imagining a group of boys at Jesus Camp, maybe undergoing aversion therapy and getting zapped as hard-core pornography is flashed across a screen. Or maybe people envision men in lab coats with bushy mustaches administering Rorschach tests. All of this makes conversion therapy sound like a campy backdrop for a rom-com. Something But I’m a Cheerleader and its recent parody, the “Silk Chiffon” music video, both do in gleeful Technicolor.

Back in the car, my parents told me the psychologist said he thought I was incurable. On the three-hour drive home we did not talk about what to do next. The Protestant way was always to remain silent and argue about where to stop for lunch. We pushed it down and reached a temporary truce. I decided to stop hanging out with the high-school senior I had a crush on. I started asking everyone how they knew if they were straight. The local stoner asked me if I liked gay porn or straight porn better, a simple question with a simple answer. My parents decided I should move schools. Across the street was a cupcake store that became famous for refusing to make a gay wedding cake. Before he was vice-president, Mike Pence was my art-history teacher’s neighbor. A classmate of mine’s dad was a conversion therapist.

Conversion therapy is often thought of as the practice of attempting to change one’s sexual orientation from homosexual to heterosexual. But it can also include the practice of attempting to change one’s gender identity from transgender to cisgender, something currently happening at an alarming rate to trans children. It’s still legal in many states, including my home state of Indiana, where it may soon be illegal to provide trans-affirming care for children.

My parents and I continued our don’t ask, don’t tell policy, and the guilt never fully subsided. I knew God rewarded only straight cis believers with eternal life. One night, after watching twinks kissing on my computer screen, I messaged my classmate’s conversion-therapist dad on Facebook at three in the morning. He responded the next day, saying he could help. He was a Christian counselor, someone who could offer spiritual guidance from a little office on the top floor of his house. As I moved closer to God, he said, I would naturally find myself in a better mood. I wasn’t just promised heterosexuality; I was promised happiness. He told me the goal wasn’t to change me but to bring me into full alignment with God.

My conversion therapist had a simple explanation for my queerness. It was my parents’ fault, he said. Intense mother, absent father: Case closed. He asked me about my family dynamics as if only nurture had played a role in my upbringing. I didn’t really buy it. My sexuality seemed so much more complicated than that. It felt like he had taken Freud and turned to a random page in search of corroborating evidence. The pieces of the puzzle didn’t fit together. I remember watching my parents go in and out of one session where they were required to talk about our household secrets. They walked out in silence with pursed lips. On the way home, we got Cokes from McDonald’s, our wind-down ritual.

I saw my conversion therapist every week. He was, I realized, kind of queer himself. He had one earring, glasses, and buzzed black hair. A few days after Lady Gaga released her 2011 single “Born This Way,” my conversion therapist went back and forth on the idea of innate queerness. If there was a gay gene, he told me, then we were all born sinners. He sometimes mentioned his wife and two kids. The elephant in the room was that I saw them around school. They knew I was seeing him, and I’m sure they knew what he did. In his office, he would ask me what was going on in my life. Like normal talk therapy, if it had only one specific outcome. Whenever I stumbled and fantasized about men, I confessed my sin and we tried to figure out what was missing from my life that made me turn to the emptiness of homosexuality. My inability to perform gender correctly was always part of the equation. I held coffee cups wrong. I crossed my legs wrong. I preferred hanging out with women to men.

I tried to date girls and told my conversion therapist about picnic dates and homecoming dances, but nothing ever clicked. I didn’t want to kiss them. The conversion therapist told me the electricity would come. The truth was it wouldn’t come until I was a woman myself.

My weekly sessions weren’t the only spiritual education I was receiving. I’d started having nightmares. My dad gave me St. John of the Cross’s spiritual tract Dark Night of the Soul, and I spent a few days intrigued by the erotic anguish of suffering. I tried to journal through my season of doubt. As my parents and I searched for the cause of my queerness, demons were one possibility given serious consideration. My grandma’s first husband was gay. Perhaps he’d passed on a family curse. Objects were blessed and purified, an oil cross was drawn on my window. For years, I was convinced I was evil, one wrong step away from demonic possession. Sometimes I peered through tomes about spiritual warfare on the family bookshelf. Homosexuality, bestiality, sexual abuse, and Buddhism were all possible signs of satanic influence. Such sentiments didn’t seem absurd at the time. I stared at clocks, afraid the world was about to end, worried I would not make it into the kingdom of God.

After my first full year in conversion therapy, I crashed a car in front of my church. I don’t think I was looking for my phone, I only remember that one second I was fine and the next a telephone pole was a few feet from my body. Was it on purpose? I don’t think so. If it was, it was a poor attempt. A man ran out of the apartment complex across the street and asked me if I needed a drink. When the police arrived and questioned me, I realized the car was being towed away and I’d forgotten to retrieve the Fiona Apple CD I was listening to. Me and my dad never talked about it again. We pushed difficult memories to the back of the closet.

I was 17 when I first hooked up with a guy in the woods. Immediately afterward, I went to church in tears and sang, “God’s not dead but surely alive, roaring like a lion.” I told my therapist at our next session. “It’s harder to go straight once you’ve had an experience,” he replied.

The business of change is a tricky thing. So many want it so badly. For a while, I, too, believed I could change. I could be free. Freedom meant freedom from sin, not freedom to sin. I believed sexuality wasn’t fixed, that I could be straight. Later, in order to cope, I decided it was fixed and that meant I was not a sinful gay but a natural gay. Now, yet again, I’m less convinced sexuality is fixed. Why does it need to be?

I didn’t talk about conversion therapy with my friends at high school. Instead, I talked to other Christians at my church. When I told the worship leader at church I was gay and trying to be celibate, he let me play in the Sunday band even though I was terrible. I slowly strummed a C chord in a cold sweat, a few beats behind everyone else. “I don’t know what to say,” he said. The truth was the entire church knew about me by then. Once I was in a bathroom stall and overheard two boys wondering where I was. “Probably off cutting,” one of them said before they laughed and left the bathroom.

There was one moment where things could’ve gone differently. My sophomore-year art teacher took me aside when she found me sobbing in study hall. I didn’t give her a play by play, but I muddled through what I could say out loud. After my weak explanation, she looked me in the eye and told me I should focus on school. “It’ll get better,” she said.

It did not get better, but I did eventually make it out. At the end of my junior year, I convinced myself and my conversion therapist that I could be celibate. The sin was the practice, not the identity. I came out in college as gay in spite of the lingering fear I was evil. My college was only about 50 miles from home. After reading Mary Oliver poems and watching Laverne Cox talk, I sent a long letter to my parents explaining everything, and my mom decided to reach back out to my conversion therapist. He told her I was going to go to hell.

Eventually, he sent my mother another message: “I’m sorry I said that. My wife has cancer.”

Many years went by before me and my parents could even broach the subject. We didn’t have the same emotional facts. I tried to explain how harmful conversion therapy was, but they told me they thought he was a regular therapist. In the meantime, I’d tried everything I could to find salvation in the secular world. In feminist punk collectives, in dating, in books, in therapy. I wanted someone to tell me they loved me. Not because of my gender or in spite of it. Not with their words but with their body.

When I came out as a trans woman, my dad sent me a text telling me he was worried I would never be happy. We wouldn’t have a substantive conversation again for many months. He went into a coma because of complications from COVID. For a while, we thought he wouldn’t make it. I traveled back to Indianapolis for the first time as a woman. My mother told me my dad loved me even though I was trans — he just wanted me to be happy. I couldn’t prove to anyone that my life would always be happy. I couldn’t prove anything. I could prove only that life could either possibly be worth living or not worth living at all. I drove by all the churches where men had warned me about the fiery pits of hell as I blasted Phoebe Bridgers in my dad’s car.

I asked for some time alone with my dad while he was on a ventilator. I told him I loved him. After helping my mom sort the bills that needed to be paid, I got back on a plane and returned to my tiny apartment in New York. I had to get ready for facial-feminization surgery at Lenox Hill.

When my dad woke up a few weeks later, I had a new face. As they unwrapped the bandages and gave me a mirror, I stared back at the soft jaw and little nose that had cost me my ticket to salvation.