Keep It Moving: Welcome to the Cut’s sports section. Like your favorite sports bar but without the mansplaining.

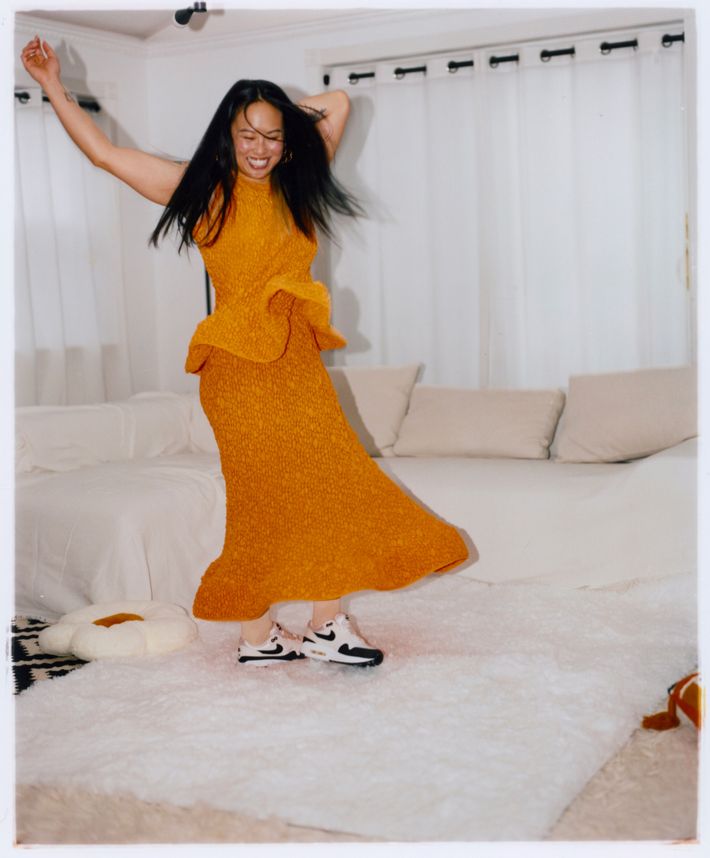

Sunny Choi tells me she’s known for her smile. Watch any of the many videos of her break-dancing — or as she and most other dancers call it, breaking — and you’ll see it: a wide, uncontrollable grin that stretches across her face as she contorts herself fluidly across the floor, stretching up into the air one moment and folding into herself, still floating, the next. The grin is not so much smug as it is delighted; she is having the best time, every time, and her joy is contagious. It’s fitting, then, that Choi, with her signature smile and her absolutely bonkers ability to twist her body into nearly any shape while keeping with the rhythm, has been chosen as the first female break-dancer — or as the lingo goes, B-girl — to represent the United States at the 2024 Olympics.

The minute Choi opens the door to her sun-filled home in deep Queens, I am greeted with a near-overpowering hug from Reign, the large honey-brown dog she co-parents with her boyfriend. Choi and her boyfriend, also a break-dancer, moved here a month ago, but there’s not a box in sight. I spot a bare expanse of floor bordered by a side table and an impressive sneaker collection. It’s actually what prompted the move: “That space is for me to dance,” she says, gesturing toward the clear area of the room. “As long as Reign doesn’t torment me. Sometimes I can get her to the couch, and she’ll sit there as I’m dancing. Other times, she thinks that we’re playing.”

Although she didn’t start breaking until she was in college, Choi has been dreaming about this moment since early childhood. Growing up in Louisville, Kentucky, she was a serious gymnast on track for the Olympics. When she turned 12, she had to decide if she would follow her dream or take the financially stable route. She chose AP classes and a business degree. Even after she became deeply involved with her college’s breaking community, she took a series of corporate jobs, eventually becoming the director of global creative operations for Estée Lauder’s skin-care branch.

Now, Choi is a year into full-time breaking. Devoting herself entirely to what has been not just a sport but an outlet for creative expression and a source of community has helped her connect more deeply with herself and her emotions than ever before. These days, she’s allowing more than just her smile to peek through.

Congratulations on qualifying for the 2024 Olympics. How do you feel?

Most days, more anxious than anything else. But there are days when I’m excited or grateful. There are also moments of pride, when I’m excited to represent the U.S. and breaking and New York.

Until pretty recently, you had a full-time job at Estée Lauder to juggle along with breaking. After leaving your job to focus all your time on breaking, what has the transition been like?

It’s been about a year since I quit, and I haven’t ever been happier. It’s so different. I thought I was gonna have so much more free time — no. But I have so much more mental space than I ever did before, because previously I was constantly extremely burnt out. I was going to practice four or five times a week outside of work and then getting up before work to work out twice a week and on the weekends as well. I didn’t have any time. When I did have a moment, I was just a zombie. It was a lot.

We don’t hear as much about the financial realities of being a professional athlete outside of popular major-league sports. Was quitting your job something you had to save up for? What has it looked like for you financially?

This is a small sport. It’s extremely hard because it’s only the one percent that gets enough money. Everyone else is really hustling. I decided I was probably going to do this and quit at some point halfway through 2022, but I stuck it out another six or seven months because I knew that I needed to save up. In 2023, I had to pay for all my flights to all the events to qualify, and I had to pay for all my stays, food, training, everything. I knew I was gonna have nothing coming in initially, so I planned for that. I was banking on a sponsorship coming through toward the end of the year, and I got lucky.

But I’m also the first to qualify and ranked No. 1. So for me, it’s going to be easier than it is for a lot of other people out there. I was just watching my bank account drain. I’d never done that in my life; I’d always been working corporate jobs and making money. Now, I’m comfortable because I have a couple of sponsorships. I’m in a very special, privileged position. After this, I’m hoping to open a dance and community center, so a lot of that money is gonna go toward funding a business. I’m also not trying to make a million dollars. I just want to be comfortable.

When the Olympics finally recognized breaking as a sport in 2021, did that inspire you to dance full time?

It took me quite some time to even come around to that decision because I was scared of giving up what I had and afraid of what kind of future I could have in breaking. At that time, I didn’t see a way that I could make enough for me to live at the level that I want to. It wasn’t until at least six months later that I finally decided that I was gonna do it. I remember going to a breaking camp we had, and the coaches were like, “Who’s going for the Olympics?” Everyone raised their hand, but I was like, Maybe. The pragmatic part of me knew I couldn’t do both. I knew I couldn’t keep my job. So it was really: Am I ready to quit my job for this?

Breaking has been rooted in community from the beginning, right? How did you get into it?

My interactions with it over time have been so different. Initially, I was intimidated, but it was more about fear of rejection. I don’t think at that point I had really accepted myself as a person. I mean, it wasn’t until recently that I started even delving into how I feel about my Asian American identity. I always felt like an outsider, but I think I was excluding myself versus the community actually excluding me.

I found good friends in the scene, and it was my escape when I was in college because I really didn’t want to be at the school I chose and I didn’t want to do what I was doing. Breaking was my outlet into something that was more genuine, more true to me, where I could really express myself. The group was very eclectic, and it was pretty diverse. At UPenn, where I didn’t feel like I fit in, I was like, Maybe I could fit in here. I had found a group of people that were a bit dorky but also had some edge.

Do you remember the first time you danced?

At first, I was too shy to actually dance in front of anyone. I used to sit in the corner and watch everyone else dance. I constantly was like, I suck at this. I can’t do this. But I didn’t want that to stop me. One of my goals was to be able to express myself. I feel like I’ve only gotten to that stage more recently, in the last year or two. So it took 15 years for me to get there. It’s been a process. But I always knew I wanted to be able to be free, to let go of everything and just be there: me, floor, music.

The breaking culture has changed a lot over the years, and it’s different in every single country. Because you’re participating in a dance, you can go to any country, find some breakers, and you can dance together. It’s just a way to share that is so different from having to have a conversation when language can be a barrier. I think it’s such a beautiful thing to be able to do.

You were involved in gymnastics from a very early age. Did you always see yourself as an athlete above all?

I started when I was 3, and I did it until high school. I did play piano, too, but I hated it. When I quit gymnastics, I was really lost. I didn’t know who I was or what to do with my free time. I never considered myself an athlete. I was “just a gymnast,” you know? Even now, I’m starting to see myself as an athlete, a more holistic view of what an athlete looks like.

The South is not necessarily the easiest place to grow up as an immigrant. How did that influence you and the way you thought about your future?

The Asian culture of being a high performer and always having to be the best heavily influenced who I was as a kid and who I am even today. Growing up in the South and looking a bit different, getting made fun of for being Asian, I always felt different. It was easier to go on the path of being in the gifted and talented programs and taking AP classes, kind of fitting into that stereotype that definitely existed for Asians in Kentucky. I sort of fit into that mold, but I always have had this rebellious streak. I didn’t want to fully fit in. I took all those classes, but I fell asleep in those classes. I still got straight A’s, but my brain was all over the place. I had this clear vision that I needed to be financially stable and have a job that would provide for me. From a pretty young age, I knew I didn’t want to have to depend on anybody else. There were complicated family dynamics. I wanted to be independent. I think that was really what drove me to be such an overachiever. But I was always interested in things that were more creative. I took a fashion class in high school and I loved it. I ended up making my prom dress.

Do you see yourself as creative now?

It wasn’t until recent years that I have finally allowed myself to believe that I’m a creative person. My whole life, I was like, I suck at anything creative. I’m not creative at all. I’m so analytical. I’m a little bit of everything. My tastes are all over the place. I’ve done a lot more introspection, self-discovery work, and working through some of the issues that I have. A lot of it comes through breaking. I definitely cry a lot more than I used to. Before, I basically didn’t cry at all. I feel like I’m much more in tune with my emotions and who I am today and much more open about it.

What has that journey of finding who you are at your core looked like?

People have always talked about my smile when I’m breaking, and I’m always so bubbly. I was thinking about that, because somebody actually said to me before a battle, “Bring everything with you out there: all the pain, everything that you carry, because nobody can take that away from you.” When she said that to me, I realized I don’t bring everything with me. I always just smile. There’s only one emotion. Why am I doing that? I realized that I use that smile to mask, all the time. This happy, bubbly personality, this person that showed up to work every day with this big smile on her face, ready to get work done, is not the real me. It was the person that I showed to the world because at that time, it was basically the only way I could function.

Of course there are times when it’s genuine, but it’s crazy to think that that is somebody 24/7. We all have a range of emotions. It took me a couple months to unpack that through dance.

Out of everything you’ve tried, why do you think breaking stuck?

Breaking is, for most people, very much a freestyle art form. We don’t know what song is going to turn on and then you just have to be in the moment. The reaction is also different depending on who you’re battling and how you’re feeling that day. Nothing is choreographed. There have been times when I’ve gone out there and done something brand new in a competition. The music just dictated a motion that I hope wasn’t terrible.

What does it feel like to be representing multiple identities on the world stage?

It was always the American part of the Korean American identity that I really struggled with. America is so divided ideologically. What is it to be American? What does that look like? Does it look like me? I don’t think so. It was, weirdly, the Olympic movement that’s helped me come to terms with that. Seeing everyone come together for the sake of sport and share in these moments of unity actually is extremely beautiful because there’s so many things that pull us apart in our everyday lives. I think maybe that’s what it means to be American. It’s about community. You don’t have to represent every piece of everything.

What are your hopes at the 2024 Paris Olympics, for yourself and also for the sport?

I just want to go and have fun. Winning gold would be great because that’s what I’ve wanted since I was a child, although I feel like it’s not really going to financially change things. I have so many mixed feelings about it.

One of my hopes for the community is that there will be more financial opportunities: More people looking at breaking, more people wanting to put their kids into schools. Breaking is so diverse. Sure, we have our problems too, and nowadays we do have studios where people are paying to start learning. But you can also just show up to a community center and start dancing and learning from the people there. Some people just start in their living rooms, watching YouTube. I wouldn’t be happy without dance. I hope more people give it a chance and stay open-minded.

How do you envision the community center you want to open?

I want there to be a high-performance element that is still about community. I want to have a fitness center where people can cross train — historically, everyone’s just gonna practice and throw their bodies at the floor. Strength and conditioning can really help to extend your breaking career but also make sure you can still walk and move. There will be a dance space. I want the entrance to have a kind of a community feel; you walk in and there’s some space to hang out. I’d also love to have enough space to have some quiet rooms for kids who need to study or parents who are waiting for their kids and need to take a meeting. That would be my dream.