I don’t think about my father. Consciously, I know this to be true. Subconsciously, I know it’s a lie because I have vivid memories of a classmate at New York University asking why everything I wrote was about my relationship with him. I avoided therapy for years after that. Because she was right.

I’d managed to finally reach my dream school, that “glorified state school,” according to Gossip Girl’s Blair Waldorf, and I got to wander Greenwich Village scribbling ideas for scripts in my notepad at late-night diner Cozy Soup ’n’ Burger like a mix between Spike Lee and Carrie Bradshaw while also slinging cupcakes for below minimum wage at Magnolia Bakery. Most of my time at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts involved me writing plays and screenplays that were my brain’s attempt to work out my lingering daddy issues.

I do think about him, I suppose, since it’d be impossible not to do as a writer who crafts fictional stories. I mine my family dynamics for inspiration like most of my gay forefathers of dramatic writing: Tennessee Williams, James Baldwin, and Tony Kushner, to name a few. So, let’s talk about Andre, a man I have maybe three actual vivid memories of. (On the occasion when he is discussed, it’s rarely in front of me. My family is very good at burying topics, like the Fisher family from Six Feet Under, but our funeral home is metaphorical, and all the bodies are familial strife.) My most distinct memory of Andre is arriving at a family gathering — his side — on the other end of town. His family had frequent cookouts that included mac and cheese that wasn’t made how Gran made it, so I never ate it, and me sweating through my shirt after being shooed from outside with whatever book I was reading to be forced into interacting with cousins whose names I couldn’t even remember and only saw once a year.

I was usually taken by my paternal grandfather, Henry, who we all refer to as Papaw. He has stayed in my life despite Andre’s absence. Upon arrival, I’d be told earnestly by multiple aunts and uncles, “Your dad and brother were just here!” Half brother, for the record. I have a half brother I’ve met maybe once in my life. The performance the relatives on my dad’s side put on every time I saw them, as if they didn’t know I’d had no relationship with Andre since my sister was born, was insulting enough to make me never form a relationship with any of them. And at this point, who knows if there are more half siblings I’ve never even heard of? Showing up at extended-family events hoping to run into Andre was a lot like waiting for service at Soho House. It’s not happening anytime soon, but good luck!

My graduate school writing class was a lightbulb moment for me: I realized that your relationship with your parents does influence your art — not just the art you create, but the art you consume and how you interpret it.

Our own paternal and maternal issues are never more evidenced than through the types of sitcoms we enjoy. In the 1950s, Hollywood was very insistent on upholding white patriarchal values: that’s why we had the Cleavers on Leave It to Beaver and the Andersons on Father Knows Best — a presumptuous title that surely has proven to be an oxymoron at this point. Over time, audiences grew to want to watch maternal figures on TV rather than paternal ones. Working dads rarely knew what the hell was going on in their homes during the day, and advertisers realized that women might want to see other women on TV solving problems like they had to in their everyday lives. But soon, the moms on TV became the ones actually watching people’s kids.

It cracks me up whenever parents today are worried about how much time their kids spend looking at screens, because from middle school to high school, millennials woke up and watched syndicated TV in the morning: usually cartoons on Disney, Charmed, or Saved by the Bell and USA High, a two-season show that aired on USA Network about American kids in a Parisian boarding school that inexplicably has ninety-five episodes. It made no one famous and I’ve never seen any of the leads ever again. If you told the average millennial this show never existed, they’d probably believe you or likely mistake it for the one-season Ryan Gosling sitcom Breaker High, about a high school on a cruise ship.

At school, most teachers had figured out how to stick their students in front of computers to avoid interacting with them during the manifest destiny era of the internet, which involved us learning HTML, playing Number Munchers and The Oregon Trail, and spending copious amounts of time crafting the perfect AIM away message. AOL Instant Messenger was the de facto chat room for all high school students. When you were unavailable to chat, you would write a usually clever message about what you were doing instead of sitting in front of a computer, or you’d just put Fall Out Boy or My Chemical Romance lyrics as a subtle hint at a crush you had or a friend you were upset with.

Then, back home, millennials were once again glued to their TV sets until dinner and then again after dinner and then once more after they were sure their parents were asleep. This is how we watched the sexy MTV soap opera Undressed that aired after ten p.m. and included story lines involving threesomes and an introduction to the fact that college apparently meant spending a lot of time in the laundry room, not just for laundry, but also for sex.

But back to sitcoms. Not to be a BuzzFeed personality quiz, but the sitcoms you watched in your formative years tended to mirror the family unit you wished you had. For many American families that didn’t represent the nuclear family, sitcoms were aspirational. Families stuck together no matter what — except for the characters who were written off shows like they never existed — and always hugged it out at the end of the episode. For Black millennials, there are three sitcoms that tap into our unfulfilled desires or, as I will call it, wish fulfillment for an idealized family unit, wealth and privilege, and generally being regarded as “cool.”

There’s the show we all love because it’s a good show: The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. There’s the show that we all love despite it being bad: The Cosby Show. And then there’s the show that has not been fondly remembered at all and has drawn the frequent ire of millennials whenever they want to go viral online with a hot take, but it’s actually great: Family Matters.

The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air is an indisputably excellent show. If you hate it, find some taste. Debuting in 1990, it was a bridge from a decade of Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous culture to the implosion of late-eighties and early-nineties hip-hop culture. It was for everyone who watched Dynasty and secretly wished the real star was Diahann Carroll’s Dominique Deveraux. Fresh Prince was Black excellence bait. Philip Banks was the stern, lovable father we’d seen countless variations of on TV before — but this one was Black. And wealthy, not because of a job in entertainment or because his blue-collar business blew up like George and Weezy’s, but because he was a prominent, well-respected judge. The Jeffersons represented the so-called American Dream that we’re all constantly striving for, but Fresh Prince existed in a world where Black people were able to thrive as equally as their white peers. Or so it would seem.

Many of the best Fresh Prince episodes reminded the characters that no matter how much wealth they accumulated, they were still Black and would be treated as such, like when Will and his cousin Carlton are pulled over by the police for driving a nice car.

Philip’s wife, Vivian Banks, was the dignified, regal (and rich, don’t forget that) mom many viewers wished they had. Hilary Banks was the rich-bitch daughter who everyone secretly wished they were, even if they told themselves they’d never be as obnoxious as she was, but you probably would be just as obnoxious if you were gorgeous, light-skinned, and born into a wealthy Black family in Los Angeles. I would be! Hilary became such an aspirational icon for a lot of Black girls that referring to them as a Hilary Banks was shorthand for calling them uppity and white-acting. The same insult could be lobbed at boys by referring to them as a Carlton Banks.

Carlton was the annoying brother who acted as a representation of viewers’ own irritating siblings. He also dressed like a yuppie and spoke in an affected (white) manner and looked down on people with less privilege than him, which often caused him to clash with his cousin Will and other Black characters on the series. He was one of the first television personifications of Black excellence as a negative and a means to achieve white approval. In contrast to Hilary and Carlton, their cool younger sister, Ashley, was the first to befriend their cousin Will from Philadelphia. She was more in tune with Black youth culture. Ashley dressed like a regular Black teenager in the nineties rather than someone trying to fit in on Beverly Hills, 90210. Though she also existed in a world of privilege, she rebelled against it more than her siblings did.

Then there’s Geoffrey, the family’s butler. It is fair to say the majority of Fresh Prince’s viewing audience didn’t have a butler at home, which is why his role’s purpose on the series was dual — to show how rich the Banks family was, but also to mock them for how privileged they were. If the Bankses were going to be a relatable family, you needed a regular cast member to knock them down a few pegs in each scene.

And then there was the series’ protagonist, Will, played by Will Smith. Smith, then part of the rap duo DJ Jazzy Jeff & the Fresh Prince, would go on to become an even more famous rapper and movie star beloved by Black and white people alike … until he slapped Chris Rock during the 2022 Oscars telecast. If you’re reading this in a distant future where the Slap is not something you can immediately recall, first, congrats to me for someone reading this long after I’m dead. Second, I hope that since then everyone has regained their collective minds and gotten over the outrage that ensued.

On Fresh Prince, the theme song introduced Will Smith as the audience’s surrogate, an everyman who found himself transported to the kingdom of Bel-Air. If only we could all be plucked from our circumstances and sent to live in a mansion in Bel-Air, complete with a butler. After one fight in his hometown of Philadelphia, Will was shipped off to live with his rich family relatives (“I got in one little fight and my mom got scared. And said, you’re movin’ with your auntie and uncle in Bel-Air”).

There was an unnecessary 2022 reboot of the series titled Bel-Air, which reimagined the series as dark and gritty. It seemed its creator, Morgan Cooper (who initially made a gritty, pretty fantastic short-film take on the series), intended to add emotional depth to the series — an exploration of gang violence and being Black in white spaces, for instance. But that depth already existed in the original series, and the reboot only served to make the subtext of the series the text. Any Black viewer of Fresh Prince was astutely aware of what it was like to be Black in America in the nineties. Therefore, the series operated not only as a “what if?” to viewers who could imagine themselves living bougie in Bel-Air, but also had a built-in commentary on Blackness and the youth culture of the nineties.

An exploration of racism is central to the show, such as in the aforementioned episode where Carlton gets pulled over by the police. The show hints at our responsibility to learn our own history in episodes like the one where Will is doing worse in his African American studies class than the white students.

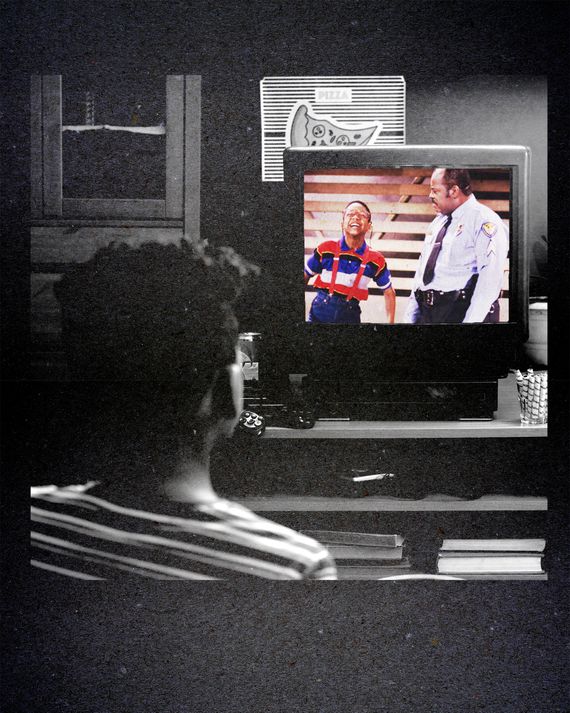

But the episode that most resonates with me, and perhaps with many Fresh Prince viewers, is when Ben Vereen appears in season four of the series as Will’s deadbeat father, Lou. The scene seems to always be brought up when mentioning how “real” the series gets (“real,” as in a dramatic episode that you took seriously, as opposed to a “very special episode” that no one, not even the people writing it, could have ever taken seriously). The appearance of Lou is mostly to service Will’s relationship with Uncle Phil. Lou upset Phil from the jump, and Will’s quick attachment to his biological father causes him to lash out at his surrogate father. “I’m sorry everyone can’t be as perfect as you,” Will says to his uncle Phil, admonishing him for not even being willing to give Lou a second chance after he apologizes for abandoning his family. Will plans to leave his home in Bel-Air and go on the road with his dad, telling Phil point-blank: “You are not my father!” But as expected, Will’s biological dad essentially ghosts him. There’s no real explanation for it other than Lou is a terrible father.

Nor is there motive for his sudden appearance in Will’s life. Is it guilt? Or is that just a motive Will and the audience create in their minds, the same way I come up with my own motives for why my dad stopped being in my family’s lives? There’s a very emotional moment where Will cries and asks his uncle Phil, “How come he don’t want me, man?” and it’s one of my favorite scenes of TV, if only because a Black male gets an opportunity to be completely vulnerable with another Black male, which was practically unheard of on TV in the nineties and is still pretty much an anomaly today.

Fresh Prince holds up incredibly well on rewatch not only because it’s funny, but because it taps into the desire most Americans have for a strong family. Granted, it’s been instilled in us by the patriarchy or whatever, but when you watch the Banks family on TV, you wish they were your parents, not just because they live in a mansion, but because there’s a sense of a mother and a father with a strong moral compass. Things I didn’t have, things I didn’t know I craved. Or maybe I just really wished my ass were that rich.

The same, obviously, can be said about The Cosby Show. Cliff and Clair Huxtable were the model image of Black upward mobility when the series debuted in 1984. With a dearth of positive images of Black people, let alone Black families, on TV, the Huxtables operated as a new Black American Dream. Cliff is a well-respected OB/GYN with his own practice, and Clair is a lawyer without an E in her name because she’s not like you regular bitches, okay? The Huxtables began the series with four children. Denise, the free-spirited bougie-boho daughter with a mix of hairstyles from locs to tomboy cuts, portrayed by Lisa Bonet, eventually becomes the show’s most popular character due to Bonet’s screen presence and budding celebrity.

There’s Theo, the perennial-screwup son who usually learns a lesson at the end of episodes centering him. Vanessa and Rudy are their other daughters, and I frankly don’t remember a single thing either of them did on the show, but they were very cute! Midway through the first season, a fifth child was introduced: eldest daughter Sondra, who was off at Princeton and signifies the overall problem with The Cosby Show. Sondra was introduced because Bill Cosby allegedly wanted to show the Huxtables successfully raising a child who was a college graduate. The reason I hate The Cosby Show is that very few creative decisions on the show were made because they were entertaining choices. They were made because they were choices that made the Huxtables look like a Good Black Family. I have never had a conversation with anyone who remembers The Cosby Show fondly as an entertaining show. Being like the Huxtables has become synonymous with having your shit together, sure, but the show wasn’t particularly funny.

And most of the Theo story lines revolved around his father’s disdain for him. And every Denise story you remember as entertaining was stolen from A Different World, a far superior TV show. Any show that introduces us to Whitley Gilbert and Dwayne Wayne is already getting put in the TV sitcom canon, but to this day, the 1992 episode where Dwayne interrupts Whitley’s wedding to Byron Douglas is still one of the most iconic episodes of TV ever. There’s no singular episode of The Cosby Show that would make any list of iconic TV episodes. Most people remember The Cosby Show for the way it made them feel — at its most innocuous, it was another type of wish fulfillment series like Fresh Prince.

It gave Black viewers an aspirational but mostly respectable version of themselves on TV each week. Which is understandable there weren’t other Black people on TV at the time! But it feels a lot like the kind of show people still wish we had on TV. When people decry multifaceted Black stories and call them “trauma porn” or insist we only have slave movies in theaters, what they really just want are stories about bougie, upwardly mobile Black

folks they can aspire to be.

At its worst, The Cosby Show gave white people the impression that racism was over and that if Black people wanted better lives, well, then, they should just be like the Huxtables. I don’t particularly care what white people think about The Cosby Show, because the only ones with strong opinions about the series four decades later are probably Republicans, rich comedy writers, or dead. What Black people think of The Cosby Show, however, is something that I care about a lot.

The show is often brought up in comparison to Family Matters, which — let’s get it out of the way — has some of the most absurd writing I have ever seen on a TV series. If you happened to tune in to the series premiere on September 22, 1989, and then only checked back in for the series finale on July 17, 1998, your head would spin at the fact that a series about a working class Black family in Chicago was now centered around Steve Urkel (who you’ve never met before, seeing as how he was introduced in the series’ twelfth episode as a minor character).

The last season of Family Matters centers on Steve Urkel’s engagement to the Winslow family’s eldest daughter, Laura — sorry, only daughter, because the youngest sibling, Judy, was written out of the series in 1993 and never mentioned again — and his attempts to return home to her from space, where he was currently lost. Ironically, the series abandoning its working class roots is what earns it so much derision today, but there are very few “working-class” Black sitcoms that have succeeded beyond the heyday of 227. The late-eighties introduction of the Huxtables can be seen as a direct line from “good representation” of Black people on TV to only bougie, well-off Black people being depicted on TV, outside of crime dramas.

Family Matters was over-the-top, and yes, Steve Urkel’s campy, borderline-sci-fi and, eventually, literal-sci-fi story lines — Stefan Urquelle? I’ll get to him in a minute — and his catch phrase, “Did I do that?” did threaten to take over the series. But with as much retroactive hate as the series gets, you’d wonder why the ratings didn’t flatline before the series was moved from ABC to CBS. And that’s because people didn’t particularly mind the outlandish story lines. Black families’ TV habits in the nineties included a healthy dose of sitcoms, cop shows, and soap operas, and Steve Urkel building a machine that turns him into a cool version of himself named Stefan Urquelle and then later cloning a version of himself to make Stefan a permanent character is hardly mind-bending to audiences who’ve seen two Krystle Carringtons on Dynasty, Marlena Evans possessed by the devil on Days of Our Lives, and Sheila Carter stealing babies and surviving death every other year on The Young and the Restless.

There’s a tendency in critiques of comedy to claim something isn’t funny if it’s not the type of comedy you’re into. Slapstick and camp aren’t genres that everyone loves, and they’re not particularly in vogue right now. Most TV comedies don’t even have jokes in them, which is why network executives are surely baffled by the success of Abbott Elementary, a show that thrives on actual jokes. Most comedies on TV aren’t really funny like classic sitcoms were anymore. TV these days is full of lightly comic situations or dramas masquerading as comedies, because jokes require actual, defined characters, and defined characters are polarizing, much like real human beings. Having rewatched every single episode of Family Matters for the purpose of writing this book, I can safely say that the show is really fucking funny.

Aside from the claim that the show was never funny, there are two major critiques that Family Matters receives that are mostly valid. One: Steve Urkel is a stalker. He basically harasses Laura into falling in love with him. I’m not here to argue that he’s not giving Fatal Attraction, but I will also posit that the majority of male TV and film characters in the eighties and nine ties were male fantasies of how love worked. If you just wait long enough, they’ll eventually fall in love with you. Think of Screech on Saved by the Bell. Think of John Cusack in Say Anything. Eventually, Laura is written as actually having feelings for Urkel, but Steve’s penance is her wanting a hotter and cooler version of him (Stefan) while she treats him like garbage.

The second most common critique is that the series centers around the fact that Carl Winslow, the family patriarch, is a cop. In Chicago. He’s literally the opps. Black people have a long history of playing law enforcement in TV and films, which is in a sense propaganda to make Black people more comfortable with police and also a way for Black characters to have “respectble” jobs. Carl being a cop is no more conservative of an ideal than the entirety of The Cosby Show, so who cares? I would put a wager on there not being a single Black person who has watched Family Matters and wanted to become a cop because Carl Winslow was a fucking cop. He’s a Simpsons parody of a cop mixed with a bit of Homer Simpson himself: a bumbling father figure who is far from an advertisement for the boys in blue. I bet you’d find a ton of Black people who became cops because of Eddie Murphy in the Beverly Hills Cop movies and Danny Glover in Lethal Weapon, however.

I do have the tendency to give leeway to things that make me cry. Keep in mind, I’ve cried at WALL·E, so take this opinion with a grain of salt, but the trauma beneath Urkel’s character is that his family essentially abandons him and leaves the Winslows to put up with him. And throughout the show, he develops a father-son relationship and genuine friendship with Carl. When I think of sitcoms that made me sincerely wish for a relationship with Andre, I don’t think of The Cosby Show — my family was never gonna be the Huxtables, and most of the time Cliff didn’t even seem to like Theo.

I loved Will’s relationship with his uncle Phil in Fresh Prince, but who wouldn’t want someone cool enough to literally be referred to as the “fresh prince” to be their son? But Steve Urkel, who was kinda weird and a nerd and who didn’t fit in with anyone else, finding a father figure who, deep down, actually loved him? At a certain point in the series, Urkel’s absentee parents abandon him further by leaving the country, and Carl becomes his defacto father. If anything, Family Matters then becomes a buddy series starring Urkel and Carl — a lost kid and his father figure getting into the bizarrest of situations, like wrestling matches and cloning mishaps.

Carl accidentally electrocutes himself in an episode and nearly dies, and the series suddenly becomes a dramatic Grey’s Anatomy scene as Urkel performs CPR on him and brings him back to life just to drive home how much they love each other. I constantly think about that. Which I guess means that sometimes, I am constantly thinking about my father.

Adapted from the book PURE INNOCENT FUN, by Ira Madison, III. Copyright © 2025 by Ira Madison, III. Published by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.