It was past curfew. My friend cut his headlights and dropped me off in my driveway. From the little peaked window atop the garage, yellow light filtered. Someone was in the attic.

I walked up the pebble path that bordered the house, opened the side door, and stepped into the garage. It was hot. It was dark. The ladder to the attic was folded down, and from the ceiling-access square a faint light glowed. I heard my mother’s voice. I took a step closer to catch what she was saying.

“Mom?” I said.

I heard a click. She stopped talking.

“Beth Anne?” my dad said from above.

“Dad? What are you doing?”

“I’ll be in in a little bit.”

I walked into the house and down the hallway and peeked into my parents’ room. My mother was asleep on her side of the bed.

A few years later, when I was away at college, I learned that my father had been tapping the phone lines. My mother had been adamant: “I am not cheating. I am not a cheater. When do I have time to cheat?” But my father’s career in car sales had given him a sensitive radar for dishonesty. So starting when I was in high school, in the mid-1990s, he would climb into the attic after she went to bed and situate himself at a makeshift station he had equipped with wires, jacks, and recording devices.

Dad’s goal was to gather evidence to use as leverage in the divorce. He also used the recordings to exact revenge. After he found out that Mom bought a slinky yellow dress — a dress he thought she certainly wasn’t planning to wear for him — he cut off her credit cards. On another day, Dad traded in her car. Just before they entered divorce proceedings, in 1997, I remember my father making copies of the tapes, packaging them neatly in brown paper (this is a man I never saw wrap a Christmas present), and sending them to some of our relatives in Ohio. He wanted to show that he had proof: of my mother’s secretive behavior as well as the emotional and psychological harm he felt she had inflicted upon him. My father had a name for this body of evidence. He called them the Divorce Tapes.

One of my cousins threw his copy of the tapes into a fire — they were upsetting to his mother, and he wanted them gone. An aunt who was recorded saying “How did he do that? He’s not smart enough to tap” says she never received them. Another aunt, my father told me, sent the tapes back with a yellow Post-it attached: TOO MUCH CUSSING!

For a time, my dad would ask me to listen to the Divorce Tapes, too. “You need to know what kind of person your mother is,” he said, but like everyone else, I refused. I was going to school, waitressing, and completing an internship. I was also trying to help my older sister, Colleen. She was sinking into a darkness I didn’t understand, and I don’t think she did either. She had recently ended up in jail for putting out a cigarette in her boyfriend’s eye. While in jail, she was given a psychological assessment and a diagnosis. Every time I returned home and visited her apartment, the pamphlet the doctor gave her was on the kitchen counter in the same spot as before. I remember its green cover. The picture of a brain. The puzzle pieces flying out of it. The last thing I wanted was to listen to the stupid Divorce Tapes.

Fourteen years later, in 2009, I was at my father’s house when I came across an enormous cardboard box in his closet. It was stuffed with jacks and adapters, a portable cassette player, and dozens of Radio Shack cassettes. The Divorce Tapes. I tossed them one by one into a duffel bag and carried it to my car.

By then, a lot had changed. I was 34, not 20, and I had begun looking back on my upbringing with a lot of curiosity. No matter how vividly I thought I remembered my version of events, there was always a gnawing voice inside that said, That could be inaccurate. Childhood memories are so amorphous and fractured. Sometimes there’s just no way to tell: Was it a poem? A dream? Am I making it up?

Sitting at the kitchen table in my New York City apartment, I reached into the duffel and plucked a tape at random. Nearly all of them were unlabeled: no year, no event. I dropped it into the old-school cassette player and pushed PLAY.

Static. The dialing of a touch-tone phone. Long-belled rings hummed through the air. The click of connection. My mother’s crisp “hello.”

At first, when I started listening to the Divorce Tapes, it felt as though I was living in my very own version of Our Town. I’d push PLAY and hear my grandfather, who was now dead, talk about his Lions Club meeting. In the background of conversations, I’d hear the chirp of the cuckoo clock in the kitchen, the ting! of Mom’s spoon as she stirred her morning coffee. For many, many hours, it was 1996 or 1997, and I got a very clear idea of what my parents’ daily lives were like as empty nesters. My father was always at the dealership, while my mother, who had never worked outside the home, spent hours on the phone with her three sisters. She talked about her marriage, but they also discussed more everyday things: books they were reading, gossip they’d heard, the latest episode of Cops.

One day, as I listened to my aunt talk about the latest drama within her small town’s police department, the conversation took a turn. Suddenly, the two of them were openly talking about something I had thought of as a family secret, something that happened to my sister as a child that we had always struggled to make sense of. I rewound. It took me a minute to gain the courage to push PLAY again.

My mother’s voice: Colleen didn’t want me to have anything to do with them. She didn’t want me to have his baby’s pictures in the house or anything.

I pushed STOP.

When Colleen was 13 years old, in 1986, she visited one of my mother’s sisters in another state. She was getting ready to go to sleep on the couch when an older male relative asked if she wanted to listen to music. As my sister later described it to me, she followed him down the basement stairs, her head a helmet of pink foam curlers that our aunt had set her hair with earlier in the evening. Amid the stereo, the wall-mounted gun rack, and the silver-spangled drum set, he handed her a beer. He sidled up to her. She thought he was playing around when he climbed on top of her; she was certain he was going to accidentally crush her. She felt her underwear go down. It was her one chance to scream, and she didn’t. She didn’t want to wake the rest of the house.

The next morning, my sister picked at her breakfast, and our aunt straightened up the basement. She walked upstairs holding the pink foam curlers. My sister braced herself for questioning — What are these doing in the basement? Quietly, our aunt dropped the curlers in a Ziploc.

For years, the curlers would be the only evidence my sister believed she had. The way she saw it, her recollection of the rape might not hold up in court (“I drank some of the beer, dude,” she’d say years after. “The jury could dismiss me as being a ho.”) But those curlers in our aunt’s hands — that felt like circumstantial evidence and witness combined.

When she got back to Florida, my sister told our mother. She also told me. I was 10. Though told may be the wrong word. It was more like her body forced the information out of her. She grew out of her training bra and into a C cup. She developed purple cystic acne. She dyed her silky chestnut-brown hair L’Oréal Midnight. Migraines, dizziness — every morning she had a new reason not to go to school. Our mother was involved (chaperoning every field trip, on the PTA) and watchful, and she noticed immediately. “Are you on drugs?” She demanded. “Are you pregnant? Tell me. Now.”

My sister finally said, “Somebody forced me to have sex.” It was a grueling process to get there. She spent the entire morning clutching her stomach, moving around the house from sleeping bag, to bathroom, to bedroom, to back porch, like an animal searching for a place to die. And even after she said it, she refused to tell Mom who the somebody was. “Will you tell me if I guess?” Mom said.

Her first guess was our father. It felt blasphemous. Our father was strong, charismatic, loving, and protective toward us; he once knocked out a Hare Krishna for trying to pin a flower on me. My sister replied, “Mom! No! Why would you say that?!”

“Hey, you never know,” she said.

Her second guess was the Relative.

That night, my sister and I waited. For the cops to come to the house, for my sister to be questioned, for our mother to tell our father, and for him to go kill the Relative himself. But nothing happened. In the days and weeks that followed, Colleen would approach our mother in hopes of talking about the rape, and Mom would grow emotional. Her dark eyes glinted the way they did before she cried. And just when it seemed like she was going to talk to Colleen about it, she’d disappear. She’d walk fast to the bathroom or her bedroom and lock herself inside, like she sometimes did during arguments with our father. Colleen would stand at the closed door, knocking, apologizing for bringing it up, begging Mom to come out. She’d scour the house for a bobby pin or a paper clip and try to pop the lock. Mom would stay behind the door for a long time, and when she finally emerged, she would start slamming cupboards as though she were angry.

As for our father, we couldn’t read him at all. He didn’t mention the rape, and we didn’t mention it to him. Night after night, he came home from work and greeted us, Colleena from Adena. Bethannana Big Banana. He poured himself a drink, and my sister and I telepathically communicated: If he’s going to bring up the rape, it’s going to be now. Then we’d sit down to eat, Mom would say grace, and life continued as it always had. We played games in the driveway. On special occasions, we went out for seafood. Mom and Colleen did their favorite things together: trips to the mall, beauty nights when they lotioned their legs and painted their nails.

In the year that followed, there were a handful of moments when it felt like the rape was on the verge of being acknowledged. Today these memories have the surreal wobble of a scene from childhood, but even in real time they had a gelatinous quality.

The first moment took place inside a psychologist’s office. By the time Colleen was 14, it was as though she had two speeds: She was either in a deep, unwakeable sleep or attacking someone. Sometimes verbally, sometimes physically. Mostly boyfriends, sometimes me. My mother consulted a psychologist, who suggested family counseling. My father couldn’t make it; he had to work.

The black leather chairs in Mr. Mack’s office were soft and cracked. I swung my feet and sat beside Mom. She said she felt responsible — she should’ve never let my sister go out of town by herself. Mr. Mack told her it wasn’t her fault as she cried. My sister talked about how being raped by a relative made her feel pushed out of her family. Mr. Mack used the word incest, and an image flashed in my mind: a swarm of wasps attacking a honeycomb.

My sister kept talking. It was mind-blowing to me that she could be so open in front of adults in this brown heavy room. This was perhaps the biggest difference between us: Colleen yearned to communicate and be understood. I was an emotional mute. Distant and careful about what I expressed, I was an observer and little else.

Mr. Mack asked a question: “And the police know? It’s all been documented?”

My mother nodded.

This was the first Colleen and I had heard of any police report. We looked to our mother. She avoided eye contact.

On the ride home, Colleen confronted her: “You told the police? What did they say? Why didn’t you tell me?” She had been scared at first of going to the police — of filing a report, testifying against the Relative — but she wanted our mother to do something. To guide her, talk to her, tell her she was on her side.

Mom didn’t answer.

Not long after the therapy session, my sister and I were in our backyard, sunbathing with one of our aunts. She and other members of our extended family were visiting us in Florida, and while everyone else splashed around in the pool, the three of us lay on our towels. Our aunt sat up, took a long drag of her cigarette, and out of nowhere started telling us a story about the Relative. It was about his time as an altar boy and how he would return home with red, swollen lips. No one realized what was going on, she said, until another altar boy reported the priest for sexual abuse.

My sister pushed her leg hard into mine, and I pushed back. Our code for: Oh shit. She’s going to bring up the rape.

“They transferred the priest to another parish,” our aunt said. Her smoke and the white sunshine made her appear, disappear. She flicked her eyebrows and shrugged her shoulder. I recognized the gesture; it’s something my mother did too. Her way of saying, What are you gonna do? That’s life.

Do you think Mom really told the cops? Do you think she told Dad? Do you think Aunt _____ knows? She has to, right? Do you think she told Uncle ______? Do you think she told … anyone?” This desperate guessing game — about who in the family knew of her rape and who didn’t know — became a major source of anxiety and paranoia for Colleen in the years that followed. To deal with it, she smoked weed. It made her profoundly miserable, and she did it all day long. She started imagining that even people outside the family knew. The 5-year-old boy who lived in the house behind us, people at restaurants; she was convinced by the funny way they looked at her when she blew her nose. At times, she wondered if a neighbor was sneaking into our attic and eavesdropping on our conversations.

The feeling that most everyone did know and was doing nothing about it made Colleen feel invisible. She thought that she wasn’t believed. Or maybe our family members did believe her but they liked the Relative more. Or maybe they knew but weren’t sure if they were allowed to bring it up. It was a silent, dizzying merry-go-round inside her head.

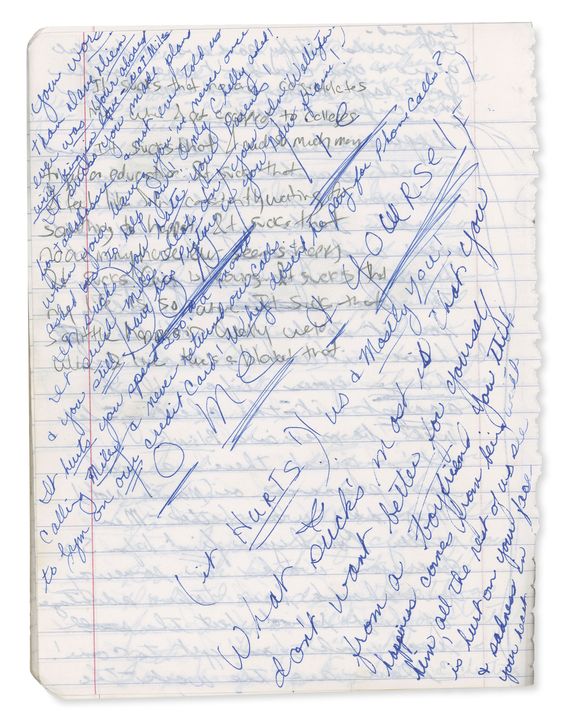

What made this silence confusing was that it never appeared as though anything was being hidden. In our house, arguments were loud. Bedroom doors stayed open. Guns were in the top drawer, bullets in the magazine. My sister’s and my diaries were public domain. If our mother didn’t like or agree with something we had written — about how boring our town was or a certain boy we liked — she’d rip out the page and hang it on the refrigerator. Or she’d write over it with her own thoughts. We’d open our diaries to the most recent entry and find her sharp, medieval Catholic-school cursive atop our teenage chicken scratch. It was like coming upon a pair of awkwardly positioned animals mating in the woods. It took our brains a moment to understand what we were looking at. Colleen responded by searching for better hiding places. I quit keeping one altogether.

Whenever one of our aunts called, my sister and I would run into her bedroom and strain our ears to listen to Mom talk. “Oh, I’ve often thought that too … God works in mysterious ways.” My sister would look at me and whisper, “They’re talking about it.”

Maybe we were wrong, though. Maybe our relatives were clueless, which is why one of them sent a Christmas card with a picture inside of the Relative holding his child. I came home from school and found the photo on the refrigerator. I didn’t say anything about it. But when Colleen, who had moved out of the house by then, stopped by to do laundry and saw it, she confronted Mom immediately and demanded she take it down.

While the phone hanging on the wall made a constant click.

Sitting at my kitchen table in 2009, I no longer had to strain. Mom’s conversation with her sisters came across the line as clear as speech in a room.

What he did was wrong. But I think she agreed to it, said one of my aunts.

I think things got out of control. I think she didn’t know how to stop it after it did happen, said my mother.

It was like riding in a broken-down elevator. Each sentence opened onto a different floor, one that I recognized but couldn’t place. Why was our mother communicating such skepticism? She never appeared skeptical with my sister. She never asked accusatory questions; she seemed to experience emotions like sadness and anger. I remember watching her cry. Didn’t I? She told us, and a psychologist, that she filed a police report. Didn’t she? Then why was she saying, on a different tape, “God takes care of that kind of stuff”? She was talking about the Relative’s mother, how if “she knew the shit about her son that everybody else knows, she’d look at him differently.” Then she said, “I will never be the one to tell.”

In one section of the tapes, our mother was at a loss as to how our father knew certain details of her daily life. She was under the impression that one of her sisters must be leaking information to my father. She made threats: If anyone testified against her in the divorce, she said, “I’ll blow this goddamn family right open. I’ll bring up the rape. I will bring up everything. I will.”

So she did believe Colleen. But why was she also saying she didn’t believe her? Was she protecting someone? Herself? Her family?

The stenographer in me sprang into motion. I opened a Word document and started transcribing. The Divorce Tapes felt like evidence, but I couldn’t understand: evidence of what? The only person who could help me think this question through was Colleen. In those years, she was moving around Ohio and West Virginia. We spoke regularly — sometimes by cell phone when she had one, or when I reached her through a friend — and our conversations largely revolved around her drug use and her day-to-day survival. Other times we’d share YouTube videos of songs that made us think of each other; she’d often send “Wild World,” by Cat Stevens. But until she was sober and stable, and until I had a better grasp of what exactly I was hearing and could deliver this information to her in person, I didn’t want to mention the tapes.

As I listened and typed, I started to feel a splitting sensation. Like the two halves of my brain were being pulled apart and a new consciousness was trying to move in. Even though the words were blunt and straightforward, I still couldn’t believe them.

In 1970, the psychiatrist R. D. Laing published a book called Knots. Every page is a dialogue that captures hidden thoughts within families. The dialogues are as short as haiku, but some are so meticulously constructed and create such tangled head trips that Laing included arrows, as in a flowchart. Knots, page 56:

There is something I don’t know

that I am supposed to know.

I don’t know what it is I don’t know,

and yet am supposed to know,

and I feel I look stupid …

I scrolled through my mom’s and my aunts’ Facebook pages. They viewed themselves as good Catholics from a tight-knit family. These are women who gave me and my sister rosaries and Blessed Virgin Mary night-light statues for our birthdays. They invited priests to their houses for dinner. I clicked through the Catholic memes:

He is Risen!

There is only one Messiah and his name is Jesus Christ.

Heavenly Father, in the name of Jesus, HEAL OUR LAND.

I pressed PLAY:

The only thing we can do is not say anything, said one of my aunts.

KNOTS, PAGE 1:

They are playing a game. They are playing at not playing a game. If I show them I see they are, I shall break the rules and they will punish me. I must play their game, of not seeing I see the game.

I played the game to a T. While Colleen argued and pleaded with our mother to listen, I’d just float down the hall and into another room. In the hundreds of hours of Divorce Tapes I listened to, my name was mentioned only a handful of times. And in nearly every instance, it’s because I was absent: “So where’s Beth at? Have you talked to Beth lately? I thought Beth was home.”

After my junior year of college, I came home for the summer. It was 1997, and by that point, it seemed as though my father’s games were causing my mother to lose touch with reality. One morning, for fun, he hid the coffeepot. My mother drank a lot of coffee. I remember her staring uncomprehendingly at the bare counter space, just as she had stared at the empty driveway when he traded in her car. “Where the hell is it? Coffeepots don’t just up and disappear,” she said, opening and closing the microwave, the oven, the dishwasher.

On the Divorce Tapes, the tenor of my mother’s voice reflects this sense of her world closing in. In the early tapes, her voice is girlish and giddy. In the later tapes, she lives in my bedroom, down the hall from my father. No car, no money, she spends her days talking on the phone and reading self-help books from the library. Her voice is deeper, slower. She no longer laughs.

My parents were both convinced that they were victims: of each other’s resentment and cruelty, yes, but also of a long-term oppressive marriage. Still, the material life they’d stayed together for never looked better. Our home was nestled in the pines. Our pool sparkled. Our lawn was lush and green. Every time I approached the front door, though, with its distorted glass panels and gold-plated, curvy handle, I was certain I was about to find one or both of them dead. The last image I have of their marriage is my mother looking gaunt and wild-eyed, walking around the house with a shotgun, searching for the double-A batteries my father had removed from the remote.

Listening to the tapes, I could hear the clicks on the phone line; they punctured the air like a stapler. My mother didn’t take them seriously until the day she found wires under her dresser, running out the side of the house. Then she began to notice. You hear all that clickin’ goin’ on? she said on one phone call. She took action: She told me she filed a wiretapping report with the police, made calls to the state attorney’s office, and brought the matter to divorce court. Apparently satisfied that this would stop our father from recording, she continued to talk on the phone all day long.

Tough shit. Too bad. Colleen’s all worried because he tapped the phone lines. My sister was selected for jury duty for a case of childhood rape, and she had spoken to our mother on the phone about not wanting to serve. She doesn’t know that he already knows about it. That the sonofabitch doesn’t seem to care.

Was this true? Had my mother really told my father? Did he really just not care? I had always assumed he didn’t know, and my sister was fine with that because she was too ashamed to tell him.

A few weeks after I took the tapes from his house, he called me: “Hey, Pumpkin. Ya listen to the tapes?”

“I did. I am.”

“All right!” In his voice, I heard the ring of thank-God redemption. “Is your mother a bitch or what?”

“You don’t come off too great either, Dad.”

He laughed so hard he snorted.

“Did Mom ever tell you Colleen was raped?”

“No. Your mother did not tell me that.”

“Why do you think she didn’t tell you?”

He answered fast: “Embarrassed of her family. Buncha hillbillies.”

I began to see the Divorce Tapes as an official record that our family had failed my sister. Yet despite how damning and candid this record felt, I still couldn’t quite grasp the nature of the offense. Had my family neglected a duty? Was it psychological abuse? In my mind, it seemed like Colleen had been abandoned. Maybe, when presented with the evidence, my mother would finally be swayed to have an honest conversation about the rape. It was something that Colleen felt she had asked her for many times, but it had gotten her nowhere. And as the ghost in the family, I had contributed to her isolation.

In 2010, my mother lived in a small town along the Ohio River. It’s where I spent the first few years of my childhood and where she returned after the divorce. Old windows, thick glass — my mother’s kitchen looked out to rolling hills. There were squirrels, rabbits, foxes, all kinds of wild birds. Dive bars were a few miles away. So was Colleen. She lived in an affordable-housing complex near the psychiatric hospital where she had been admitted. Our mother rarely visited her, and Colleen felt unwelcome at our mother’s house. Mom didn’t trust my sister. She thought Colleen would stab her. Still, in every room of our mother’s house, there were pictures of Colleen — sleeping soundly as a baby, dressed up as a punk for Halloween, fishing from a boat, me eating Cheetos at her side.

My mother and I did the things we always did when I visited. We went to the store that sold random things I was pretty sure came from spills of 16-wheelers on the interstate. Hair color and dog food. Chicken coops and douches. I think I appeared to be having a nice time. I wanted to appear normal. But inside, I felt nervous. In my mind, the Divorce Tapes were the equivalent of a heavily armed combat vehicle creeping forward on a loop of endless, unstoppable chains straight for my mother’s psyche.

What I wanted, what I hoped for, was a conversation that would lead to an apology to my sister. Maybe our mother would see this as an opportunity to repair her relationship with Colleen. This was a chance for her to relieve Colleen’s suffering, to potentially have her daughter back, and to better guarantee her entrance into Heaven. Secretly, I hoped that maybe my mother hadn’t entirely realized what she’d done. That her treatment of my sister came from a place of ignorance and overwhelm rather than lack of love and that maybe the tapes could help her explain that to us.

Two aunts stopped by Mom’s house. We sat at the kitchen table and played Scrabble.

“So, how’s New York City, Beth Anne?” In my head, I pushed PLAY.

He was older. He should’ve known better. But she told me she had a couple beers …

“It’s good. Fun.”

“You been feelin’ okay?”

… I still have the same feeling. I think she agreed to it. I’ve always said that.

“Uh-huh.”

“Talk to your sister lately?”

The only thing we can do is not say anything.

“Yeah. She’s in the hospital.”

“Again?”

“Still?”

“Jeez.”

They kept playing Scrabble (“I forget. Is yinz a word?”), and I fantasized: I’d bust out the handful of tapes from my backpack, press PLAY, and then grab them by the gold crosses hanging around their necks in a maniacal citizen’s arrest. Instead, I made words with my tiles. My aunts left, and I counted to ten.

“Whatever happened to the police report you filed after Colleen was raped?”

“It took place in another state. There was nothing they could do.” Mom flicked her eyebrows, shrugged.

I told her I had listened to the tapes from when Dad tapped the phone line. That I’d heard her talking to her sisters about the rape. That she said she would never be the one to tell.

“Oh, Christ. Those ancient things?” she said with a wave of her hand. “Somebody needs to throw them away already.”

“I want to know why you wouldn’t be the one to tell.”

“You know what? You are just like your father. Ruthless. Two peas in a pod.”

“I’d like to listen to the tapes with you. I have them with me.”

She wiped invisible crumbs from the counter and brushed her hands together over the trash.

“Mom?”

She tossed the sponge in the sink, walked into the bathroom, and locked herself inside.

I stood as close as I could to the door without touching it. “Mom?” I listened. I heard only silence.

My mother stayed there for what seemed like hours. When she finally did come out, she told me she would talk with me more, but tomorrow. She said I could drop her off at work so I had access to her car, and when I picked her up, we could talk about it then. The following night, when I arrived at her job, her co-workers said she had already left. I called her cell, and she explained that she’d had her boyfriend pick her up. She’d be spending the night at his house. On the day of my flight, she had yet to return.

I told Colleen about the tapes in 2016. She had landed in a hospital in West Palm Beach, and I picked her up on the day of her discharge. Her medication was balanced. She was happy to see me. I took her to a little park with a manmade lake and a fountain. I started as gently as I could: “Remember when Dad tapped the phone lines?” I relayed to her everything — how Dad still had the tapes, how I listened to them, the things I heard Mom and our aunts saying.

I expected her to feel sad and angry but also validated. Even if they left no impression on our mother, the tapes were at least irrefutable confirmation of the two worlds Colleen had been forced to straddle for most of her life. Maybe with this information, she could honor her life story, as opposed to being ashamed of it.

But when I asked if she wanted to listen to them, she said, “Fuck no.” The last thing she wanted was to hear Mom and her sisters talking shit about her.

To me, the tapes had mattered because they provided a modicum of proof of what kind of family we had. They gave me a foothold; they said, “It wasn’t just your imagination.” But Colleen trusted the reality the first time it happened. She had carried it with her every day, and “proof,” as far as she was concerned, was just more of the same harsh reality from which she wanted to escape. What she really wanted — what she craved — was a Reuben sandwich with fries. She headed to the car while I sat there with my tapes, which now seemed as inconsequential as pink foam curlers in a Ziploc from 30 years ago. My single-minded quest helped nobody but me.

Proof has its limitations. Proof, I realized, didn’t matter for my father. He hoped the recordings would compel the family to see our mother in a different light, but instead they decided he was the asshole. Nor could the conversations be used as evidence in court. During the divorce proceedings, the judge granted our mother the house, which she immediately sold, and an alimony award of $3,500 a month, of which my father never gave her a dime. Instead, he drained his 401(k), paid cash for a new Corvette, and spent the next ten years partying. Bitter that his proof got him nowhere, he lost his touch as a salesman and grew apathetic. If he didn’t want to go to work, he didn’t. If he didn’t have money for his mortgage, he didn’t worry about it; he’d pour himself a gin-and-tonic and go for a swim. Ten years before he died, in 2010, he lost his house. He became homeless, and honestly, I don’t think he even cared.

Proof is, or at least can be, just another fold in the knot. Today, there’s only one fact that I, Colleen, and our mother agree on: that as a child, Colleen was raped by the older relative. Other than that, hardly any of our mother’s memories match ours. The way Mom recalls it, Colleen was “already changed” before her visit to our aunt’s house; she had already gotten a diagnosis, she was already smoking weed. The rape and its aftermath did not impact her. She said that Colleen didn’t tell her about the rape for three years, that she’d protected Colleen, and that Colleen didn’t want her to tell anyone. She said nobody in the family knew for 15 to 20 years, and she didn’t remember speaking about it with her sisters or even with me. No matter how granular the detail or memory (the Christmas card, the Scrabble game, the session with Mr. Mack, the torn diary pages), she refutes them all.

Still, it was hard to learn my lesson. This past winter, in a last-ditch effort, I formed a group text with my mother and aunts. I explained to them that over the past four years, my sister had been in multiple psychiatric hospitals. “Neurologically, she is failing fast,” I wrote. “If any of you would like to reach out to her and acknowledge that she was failed as a child; that perhaps you, or those close to you, knew about her rape but chose, instead, to protect the Relative, now would be the time. Needless to say, it would be life-changing for her.” I attached the most damning clips of the Divorce Tapes. I pushed SEND.

My mother never responded, but my aunts did. Afterward, I read my sister their replies.

One of them had said: “I didn’t know about that until years after it happened and when I heard I wondered whether it was true. Why didn’t you tell Colleen to go to the police??? … You do realize that tapping phone conversations is illegal right and I’m sure that sending them to others is too!” She sent another message: “Where was your dad??? He could have taken her to the police station!!!”

Another aunt, who I always thought of as the most compassionate one, said, “I will call her. I need time to digest all that I read … We all have regrets.” Both aunts said later that they had been under the impression that Colleen didn’t want anyone to know.

Seeing their words, the aggressive ugliness of their punctuation, made me physically ill. My sister calmly rolled a joint. “Yeah, dude. Newsbreak. They suck.”

My sister coats her eyelashes in electric-green mascara. She wears a roach clip attached to the belt loop of her Bongo jeans. The only music she listens to is heavy metal from 1986. It’s the year she still lives in. She wanted me to tell this story. She hopes it will help other parents understand what their daughters could be going through, or maybe what those daughters have already been through.

Recently, I helped her move into a halfway house in West Palm Beach, a few miles from the house we grew up in. One afternoon, without much thought, we decided to drive past it. I turned onto our old street. My sister gave a running commentary: “Shit, dude. It’s comin’ up. Oh God. Next house on the right. Wow. Look at it.”

This was a single-story stucco home on a small lot, yet it had the power of a massive whale splashing out of a harbor. I gasped. My sister grabbed on to the door for something to hold. We idled in the middle of the street.

It was painted gray, not white. Every tall, dark pine tree had been removed. In their place, palm trees swayed. The pebble path along the side of the house was now stone. The front door, however, was the same — the distorted glass panels, the curvy gold handle. I watched a child walk out of it.

Afterward, we did what we always do. I took her to Target, then we drove along the Intracoastal. Sometimes on these visits, I’d lie on her bed and help her with her outpatient-program homework. A common exercise was called “reality testing.” I’d ask her the worksheet questions, and she’d answer them.

What did you dream of last night?

How justified was your paranoia today?

What kind of bad things float through your head if you don’t control it?