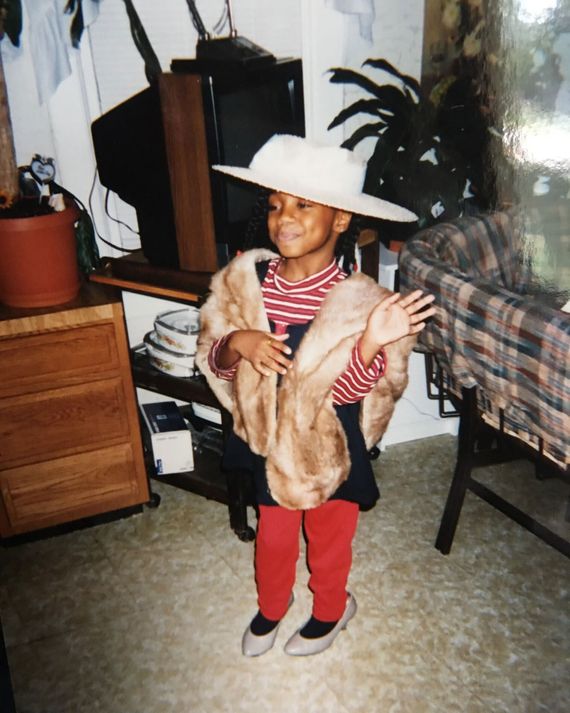

As a black girl growing up in Wisconsin, I papered my bedroom walls with a collage of images cut out of the pages of Vogue, Essence, Teen Vogue, and Ebony magazines. I loved that the photos felt like an escape from life in the Midwest and was attracted to how fashion was more than just pieces of clothing — it told a story. I never saw myself in most of the images that weren’t from Black publications, but that didn’t soften my love for them. Still, I was aware of the disconnect, that something I loved so much was clearly not made for someone like me.

A couple of decades later, I was given a much better understanding of why I felt that way. In August 2018, as a fashion editor at the Cut, I wrote an article called “Everywhere and Nowhere: What It’s Really Like to Be Black and Work in Fashion.” The beautiful chaos of interviewing people of color in the industry felt like the best and worst parts of therapy. Most conversations ended up running more than two hours. So much emotion spilled over because the experiences of the designers, models, and fashion editors were often deeply painful — they were memories that had been buried for years, on purpose.

The stories they told, from the overt racism of being called a slur in front of their colleagues to the need to code-switch to survive, were uncomfortable to unpack and complicated to wrap my head around. And yet sharing them brought joy to all of us. The response from readers was also gratifying. The feeling of being iced out, disrespected, and ignored because of what you look like was not only a problem in fashion.

Soon after, I became editor-in-chief of Teen Vogue and was tasked with making young people feel seen and heard in the middle of one of the most divided times in modern history. I wanted to make a fashion magazine that challenged the idea that if you’re a “fashion” person, you can’t still care deeply about the world around you.

When I came back to the Cut earlier this year as editor-in-chief, I knew I wanted to keep pushing to make a publication for people like me, the outsiders, those who never fit into the fashion industry’s narrow idea of what’s worthy. I wanted to expand the range of who felt welcome in our conversations and who saw themselves in our stories. I wanted all those uncomfortable things that weren’t being said aloud to keep bubbling up.

This, our “Fall Fashion” issue, is just the beginning of our chasing that beautiful chaos again. Obviously, it isn’t exactly easy. Making work that strives for both beauty and relevance is walking a fine line in the best of times. Cancel culture finds its prey in the crevices of uncomfortable conversations. Spotting an “I’m listening” social-media post in the wild or a brand begging for an inclusivity crown for doing the bare minimum is all too common. Add to that the specific kind of pressure to get it right at all times, at all costs, that comes from being one of the very few Black leaders of a publication, and the high wire can feel like it’s suspended above a pool of piranhas. A few weeks ago, I told a friend that I feel as though I have only one shot, which he was sad to hear, but it’s often how it feels.

The fashion industry has made strides in the past few years — yes, the models on the runway are more diverse, and sometimes you do see a campaign on a billboard that isn’t just white people — but fashion has yet to really grapple with its racism. After the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor last year, the industry became obsessed with doing the right thing in the smallest ways, and the complicated conversations barely happened out of concern for the optics.

There’s no easier place to watch all this play out than in the long-overdue attention that has suddenly fallen on Black and brown designers. The rush to appear supportive, to quickly publish roundups of Black designers for Black History Month without genuine investment by fashion brands to include them in future editorial plans, has done a disservice to the very designers they’re meant to help. Without dedicated mentors showing them how to grow and maintain longevity in such a fickle industry, many of those designers are being set up to fail. “It is so hard to step into the spotlight,” says Robin Givhan, senior critic-at-large at the Washington Post. “And the ones who do, it often feels they are just rushed in a way that they end up dropped into places that maybe they’re just not ready for yet.”

Instead of improving, fashion has become even more of a convoluted space for people of color like myself: Everyone is cautious about saying anything — justified or not — that could be viewed as unsupportive of a fellow person of color. White commentators, critics, editors, and influential industry leaders appear too scared to publish anything but glowing reviews, afraid they will earn a front-row seat on the conveyor belt of cancellation.

When I talked to Constance White, a former style reporter for the New York Times and former editor-in-chief of Essence, she acknowledged that a more diverse set of designers was now getting attention. “They’re definitely trying to play catch-up,” White said of the industry. “But we still see the same roadblocks.” Vanessa De Luca, editor-in-chief of The Root, has seen the way Black designers are often held to a different standard, hollowly praised while rarely being afforded the same respect as their white peers. “White people get a lot of chances to fail fast and keep it moving,” De Luca said. “And we don’t always get that same consideration.” Historically, opportunities to grow and change have been rare for Black and brown designers. Take Ann Lowe, who designed Jacqueline Kennedy’s bridal gown, which was seen all over the world; she never received credit from the former First Lady or the press. Willi Smith is often referred to as the inventor of streetwear (he grossed more than $25 million in sales annually), but he is rarely mentioned in coverage of today’s obsession with hypeworthy apparel. POC designers like Christopher John Rogers and Telfar Clemens have had to make their own way, working on the edges of fashion for years before finally gaining recognition.

In the Times profile “Byron Lars Is Still Here,” former veteran Wall Street Journal fashion reporter Teri Agins wrote about this issue in detail, chronicling the struggles of Black designer Lars, who created a dress that Anthropologie has sold more than 60,000 of and that no other designers have been able to copy because it’s so intricate, yet he’s still relatively unknown. When I asked Agins her opinion about the state of the industry as a person of color, she chuckled. “People feel like now we finally have a chance to get in,” she says. “And guess what? It’s harder than ever.”

Can we create a better pathway forward for fashion? For ourselves? The fashion critic Pierre Alexandre M’Pelé argues it’s about understanding the forces at play, namely the big fashion conglomerates, and learning to navigate around them. “I think there are power structures that are bigger, whether we want to admit it, a little bit like clouds in the sky,” he says. “And you know that you shouldn’t go toward the cloud too much because that could mean being blacklisted or having your career impacted negatively.”

I’d be lying if I didn’t say there will always be tensions between being true to the fashion industry and being true to the Black experience. An elitist industry that thrives off exclusivity won’t easily change, but trying to open the doors of fashion wider has brought me the most meaningful purpose and creativity of my career. The small moves fashion has made toward greater inclusion — even someone like me being in a job like this — have happened only because people are willing to have tough conversations. This fashion issue isn’t so much about “shaking the table”; we’re building a new table, one constructed on a foundation of respect for those who have come before us and for those leading us into the future. It is elevated, diverse, glamorous — and led by women of color.

I still don’t think I have been able to properly fathom the honor of having Naomi Campbell on our cover with a story written by Michaela angela Davis, along with a portfolio and visual anthology of iconic Black models orchestrated by our new fashion director, Jess Willis, and the first proper profile of Peter Do, who will be showing at New York Fashion Week for the first time this season. When discussing this issue with a mentor, they asked, “Are you stirring the pot again?” I laughed and said maybe, but my real hope is that this issue stirs up some emotion inside of you, whether it be praise, joy, criticism, nostalgia — or perhaps worse. Because this is for us, trying to make sense of the world and how style influences our lives. I am eternally grateful for this full-circle moment and for being back at the Cut, but most of all, for you, our readers, and the bond we share.

More From Fall Fashion 2021

- The People Who Make Those $10,000 Couture Gowns

- Am I Ready to Become a Hat Girl?

- The Global Pursuit of a Bigger Butt