I come home and take off my shoes. I wash my hands with surgical thoroughness, change into my “inside clothes,” and put my “outside clothes” straight into the hamper. Looking around, I wonder if I am okay, if the world will ever cease to feel perilous.

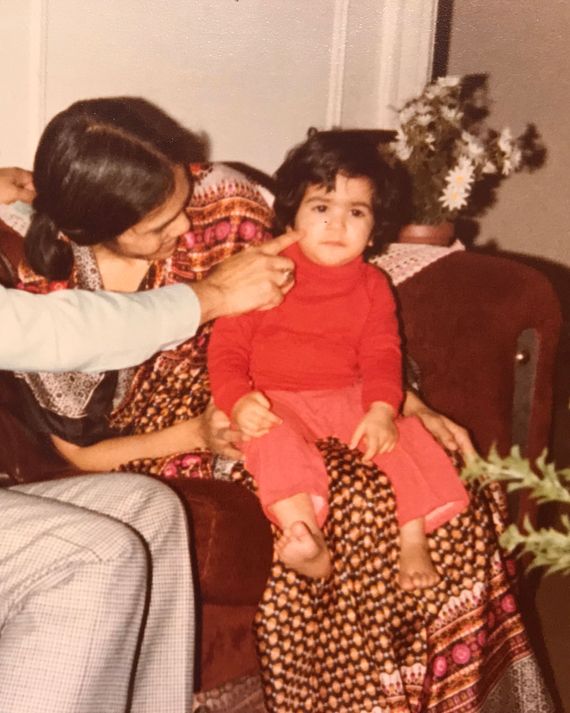

This is not a description of pandemic life but one of my childhood. As the daughter of South Asian immigrants, this was my daily after-school routine.

Last spring, my Asian American friends and I joked that everyone’s household was starting to resemble those of our childhood: the strict prohibitions, the obsessive hygiene rituals, the sharp distinction between “outside” and “inside,” and an attendant anxiety about the lack of freedom. This latter part is where the joke stopped being funny: when we realized a global pandemic shouldn’t recall childhood.

Even when the pandemic is behind us — a prospect less within reach for countries like India, currently in crisis — this anxiety may linger. Part of the tragedy of America is that despite our resources, we cannot create a country where everyone feels safe. Asian American hate crimes and prejudice are only just beginning to register in the national consciousness.

My childhood anxiety is difficult to name. There is no vocabulary for it, which is part of the problem. Growing up during the 1980s in a predominantly white suburb of Long Island, I felt invisible. This was before yoga and turmeric were in vogue, before Alanis Morissette thanked India and Elizabeth Gilbert prayed there. When City of Joy came out in 1992, my family excitedly went to see it, thrilled by the prospect of a film about India. Two hours later, my parents were slouched over in defeat; the story of slums and white saviors had no connection to the India they knew. It was the first and last time we ever went to the movies.

There were no after-school specials about the dynamics of my family home: the abuse, the oppressive silence, the shoddy coping mechanisms of my immigrant parents. They regarded the world beyond our home with suspicion. They didn’t socialize with neighbors, organize birthday parties, or host play dates. Carefree restaurant meals, leisurely vacations, partaking in American society: These were unthinkable. It’s not that we never went out, but on the rare occasion we did, the experience proved so miserable that we decided it wasn’t worth it. My parents decided we were better off staying at home. It was as though we were living through our own pandemic.

The threat was America. My parents’ anxiety took different forms. On the mildest level, they feared American culture would infect me and my brother in the virulent way culture spreads: invisibly at first, with a seemingly benign pop song or movie, and then causing rapid and full-blown alarm when, for example, I had my first boyfriend. I was forbidden from seeing him and told he would ruin my life. My socializing was confined to one or two preapproved friends: an early form of the pod.

More broadly, my parents feared what America might do to them. They experienced a powerlessness in the States that was wholly new. As Brahmins, they were treated with deference in India. Their upper-caste status gave them ready access to resources and security, privileges that members of other castes did not have. My mother was a physician, my father an engineer. Their degrees accompanied them across the ocean, but their status did not.

Contrary to glorified notions of the American Dream, my parents experienced life in the States as a demotion. They were now at the bottom of the totem pole. That the caste system is reprehensible was not something they discussed. Like most people, they enjoyed having privilege and disliked losing it.

When my mother was mugged in broad daylight in the parking lot of the hospital where she worked, dragged into a van at knifepoint by two white men, I asked her why the security guards hadn’t intervened. She snorted. “No one here protects us,” she said. “They do not even see us.”

I was in the eighth grade at the time. It was the first moment I registered my parents’ reality as more fraught than I’d imagined. My mother’s paperwork listed her as an “alien,” the official term for an immigrant then. She told me she didn’t find it offensive. It captured how she felt. The phrase “melting pot” made her laugh. “People here don’t want to melt with us,” she said.

My parents had immigrated through the H-1-visa program for specialized labor, part of the long American tradition of viewing people of color through a utilitarian lens. Borders open up to Asia when workers are required (for the building of a transnational railroad, for example) but close out of racial prejudice (the Chinese Exclusion Act). In the 1923 ruling United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind, the Supreme Court voted unanimously to revoke the rights of a naturalized American citizen, a Punjabi man who had attended the University of California at Berkeley and served honorably in the U.S. military. None of it mattered. Thind and other South Asians had their rights stripped out of xenophobic fears of “radicals.” In the 1990s, in the run-up to Y2K, American tech companies lobbied the U.S. government to allow an enormous influx of South Asian computer programmers. After 9/11, when hate crimes against South Asians skyrocketed, they experienced the same lack of protection my mother felt in that parking lot, the turning of a blind eye.

My parents were not dreamy-eyed fools. Their plan was to work in the States for a few years to help relatives back home. They left my older Indian-born brother in the care of my maternal grandparents so they could focus on their careers. My father, one of thirteen children, had countless nephews and nieces in need of school fees. My mother, an only child, wanted to help her parents.

Their plan depended on visa renewals. As a young girl, I thought the term H-1 referred to a blood test. Why else would relatives look so worried when it was mentioned? Whenever there was good news about an H-1, everyone breathed a collective sigh of relief. I figured a green card meant one was healthy. For immigrants, paperwork is a lifeline. Children can absorb this message literally.

The reason my parents ended up staying in America was simple: me. I was an unplanned pregnancy. I learned of this only recently. People imagine “anchor babies” as desirable for immigrants. For my parents, it was the opposite.

While I didn’t always understand my parents’ anxiety, occasionally I experienced a flicker of it. In my suburban elementary school, I was the only South Asian child in my year. My classmates held their noses and complained I smelled. They pantomimed applying a “dot” to their foreheads. I dreaded the appearance of that word in any written material, for I knew it would cause snickering and sidelong glances my way. Teachers didn’t offer safety. When my fourth-grade teacher asked me to describe India, she didn’t want to hear about my grandparents’ lovely flat or the way I was treated like a princess when I visited. She asked in a whisper if I had seen lepers.

My parents had different approaches to the loss of status living in America entailed. My father wanted a place where he still commanded authority. He turned to our household. Like a desperate dictator, he made juvenile grabs at power. He hit my brother so hard that he drew blood. He called me a worthless girl who would amount to nothing. He created elaborate rules so that he could have the satisfaction of seeing them obeyed.

Toxic masculinity is often discussed in the context of the loss of white male privilege: the downtrodden white guy who no longer sees a place for himself in society and retaliates through violence. But this phenomenon has long existed in Asian American households, where displaced men who feel devalued and emasculated try to assert their authority at home.

My mother’s strategy was to tell elaborate stories of India that presented it as vastly superior to America. Her logic was simple: America was the backward place, which was why she was treated unjustly. India had elected a woman as prime minister. “That will never happen here,” she declared firmly. In India, public hygiene was poor, but private hygiene was excellent. “Here, they have restrooms, but people do not wash their hands!” she fumed.

“I don’t understand,” I once said to my mother. “Is it good that I’m American, or is it bad?”

She regarded me for a long moment and then said, “That is a good question.”

On the rare occasion that I went to a white American friend’s house, I was stunned by the lackadaisical ease. None of the strict rules from my house applied. Kids wore sneakers on couches, watched TV without having to ask permission, ate Oreos and potato chips, danced in the living room. It was dizzying, a nearly bacchanalian display.

What struck me most was the lack of anxiety in my friends’ households — not that they didn’t have problems, but they could name them. They confided in me about their worries. They had seen them voiced in sitcoms and novels and magazine articles. They were on their home turf.

I didn’t know how to describe what I felt. I didn’t even know how to tell my friends why they couldn’t come over. I only knew that my friends didn’t have to follow elaborate rituals or heed strict prohibitions or listen to nationalistic propaganda in a way that meant shedding their identities. Their parents weren’t trying to compensate for a hostile environment by establishing alternate republics. They didn’t have to perform one way inside and a different way outside. They were free.

Despite being an American by birth and a fortunate member of society, I’m not sure that I have ever known such freedom. A good day in my childhood was when nothing bad happened. This put a low ceiling on happiness. My parents’ misery stemmed from feeling invisible. Ironically, this became my coping strategy. I hid from my father, accepted my mother’s stories, took up as little space as possible. Childhood strategies are hard to shed.

“Are you glad you stayed here?” I once asked my mother.

“I would have been happier in India,” she replied. “But … perhaps you will be happier here.”

I live in that “perhaps,” a threshold of possibility, hoping for an America where I can feel at ease, stretching, taking up space, finally at home.