Diaspora, capitalism, war, geopolitics, revolution, colonialism, climate change: These are just some of the monumental themes that Julie Mehretu explores in her abstract paintings of often monumental scale. The largest, most ambitious, and best known of her works include Mural, a 23-by-80-foot painting that Mehretu made for the lobby of Goldman Sachs in 2010, and the Howl (eon) I and II series in SFMoMA — which, at 23-by-32 feet each, account for a surface area larger than Vatican City’s The Last Judgement. Just days ago, Mehretu completed her newest large-scale, site-specific painting Ghosthymn (after the raft), which nown hangs on the fifth floor of the Whitney Museum alongside some 70 other works of art she made over the past two decades. Together, they comprise a mid-career survey of the artist, arriving just in time for New York City’s long-awaited spring reopening.

The words used to describe Julie Mehretu’s status in the art world are just as grand as her layered paintings are in size and subject matter. Mehretu, born in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, raised in East Lansing, Michigan, and educated at Kalamazoo College and RISD, was officially declared a “genius” by the MacArthur Foundation in 2005, upon receiving its prestigious $500,000 grant. Critics have rightfully dubbed her art-world “royalty”; at 50 years old, Mehretu’s turnover of works at auction is reported to total $21,729,529, making her one of the top-selling living female artists today. Prestigious institutions like MoMa and the Brooklyn Museum, which have collected her work since the early 2000s, have credited Mehretu with “reinvent[ing] abstraction” for the 21st century. Whitney assistant curator Rujeko Hockley resolutely declared her “one of the greatest artists of her generation, and of our time.”

I remember my own first encounter with a Mehretu painting as a kind of revelation. In looking at her work, I finally had the all-encompassing and quasi-religious experience that I had come to expect of large-scale Abstract Expressionist paintings as a young art-history student, but could never seem to muster when looking at the rage of a Pollock or the mania of a de Kooning. In Mehretu’s overwhelming and otherworldly works, I saw something far more open-ended, even inviting, that enabled me to surrender to a flood of emotion. I entered the gallery a cynic and left a convert.

And yet, despite all of her achievement and grandeur, Mehretu radiates the warmth and sincerity of a Midwesterner. Over Zoom, she spoke graciously about everything from systemic racism in American art institutions to her experience coming out as gay to her East African family. She was casually outfitted, appearing perfectly at ease in the relaxed setting of her upstate escape, the 225-acre campus of the artist residency program she co-founded with Paul Pfeiffer and Lawrence Chua, Denniston Hill, where she and her two teenage sons were enjoying their spring break. But as we traversed broad conversational terrain, I realized the most crucial term in Mehretu’s world is not one that’s been assigned to her or her work, like “modernist” or “geopoliticical,” nor one that puts her in a box, like the labels “Black artist” and “queer artist” often can, but rather one that she herself invokes most frequently: “possibility.”

She first used the word when I asked whether or not her relationship with New York, the city she has called home for more than 20 years, has changed in the wake of the pandemic. Mehretu spoke of tragedy and devastation, but also of newfound liberty. “This has been such a moment of suspension and pause, and there’s an immense capacity for movement and possibility within all of that,” Mehretu said. “It allows for a way of being in the city that we haven’t had since I first moved there in the early ’90s.”

Mehretu spent the summers between and after her college years waitressing and “immersing herself in the possibilities” of New York’s creative landscape. Having not grown up with regular access to galleries or museums, Mehretu remembers that time as one of substantial transformation and artistic awakening. “I was waiting tables and working on painting and really wanted to make sense of and find a place in [the contemporary art world]. So I decided to go to graduate school and study further,” Mehretu said. After completing her degree at RISD, she permanently relocated to the city in 2000, to do an artist residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Pieces from Mehretu’s grad-school days are the earliest works currently on display in the exhibition, which first opened at LACMA in November 2019. The traveling show’s new (albeit temporary — in October, it will be moved to the Walker Art Museum in Minneapolis) home at the Whitney is a full-circle moment for the artist, who cites the institution’s 1993 Biennial and 1994 Black Male show as crucial influences on her professional coming of age.

“This is in many ways the least ideal time to have an exhibition,” Mehretu says. “The museum is at 25 percent capacity and we don’t have any of the international tourist audience. But in another way, we have an opportunity to do an intense dive into the community of New York.” Mehretu hopes the show will expand on the typical museum-going crowd and welcome various communities to “think through the struggle in an alternative, abstract way.” The artist’s newest work — which was made specifically for the west-facing gallery and offers people on the street a glimpse of the exhibition — is one component of this mission.

In Mehretu’s world, abstraction and possibility are one and the same. “Over the last 25 years, Mehretu has forged ahead, building on the deep legacies of her creative forebears, particularly Black artists working in abstraction, like Frank Bowling, Alma Thomas, David Hammons and Jack Whitten, while also creating her own unique visual lexicon,” Hockley says. The limitless potential of abstract expression has been integral in allowing Mehretu to not only represent the complexity of her own intersecting identities, but also to transcend the limitations of any individual identity or narrative, in spite of the art world’s insistence on classifying her into reductive categories. “Being queer, being a woman, being Black, being partially East African, all of this informs who one is,” Mehretu said. “I am trying to make sense of that inside the various multitudes of culture that we all come from.”

Mehretu’s ambitious artwork depicts an amalgamation of experiences, viewpoints, and memories across epochs and continents; they illustrate the interconnectedness and chaos of a collective, 21st-century reality. “The languages of abstraction are truest to lived experience; they exist in the in-between, the both/and, the gray area,” Hockley adds. “Mehretu had an early and intuitive understanding of this, and of abstraction’s capacity to hold complexity and tell nuanced, multi-vocal stories; the rest of the world has just finally caught up to her.”

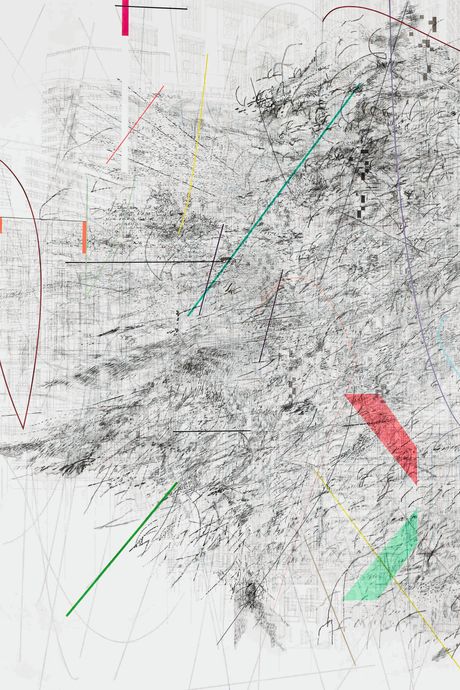

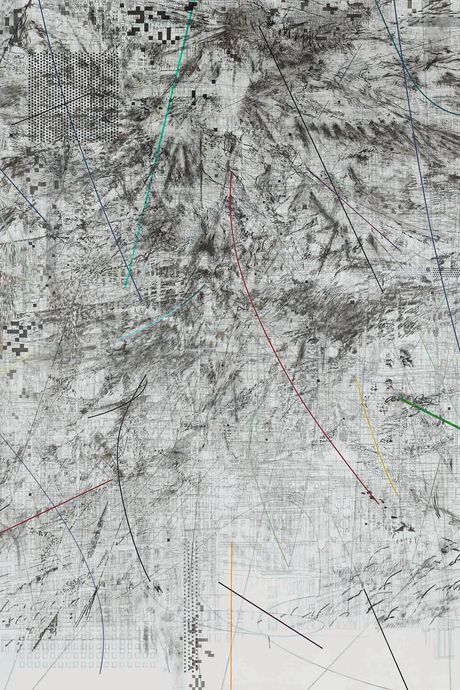

Her earlier pieces, which combine architectural drawings with systems of marks, signifiers, and cultural codes, are what she calls “story maps of no location.” These complex pieces, which poetically synthesize the influence of her father and mother, an economic geographer and Montessori school teacher, respectively, do not come with a set of directions. Viewers are left to navigate the work and draw independent conclusions. Those attempting to decipher the pieces are invited to engage in an exploratory dance. As onlookers shift their vantage point (nearer, farther, left, right), they can uncover new images and information.

In her more recent work, Mehretu has focused on a different process, wherein she first embeds what she describes as “haunting” photographs into the canvas, so that her mark-making (which eventually renders the photo invisible) derives from the emotion of the image. Ghosthymn (after the raft) was inspired by the Whitney gallery’s view of the Statue of Liberty and Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa. Beneath its seemingly infinite layers of color patches, shapes, and marks are large photographs of anti-immigration riots in Germany and England. Though imperceptible from the surface, Mehretu’s pieces chronicle the most urgent and devastating events of the 21st century, like the Syrian War, Occupy Wall Street, the Arab Spring, Grenfell, the California wildfires, and the murder of Michael Brown.

As art institutions — including the Whitney, which has been accused of exploiting Black artists numerous times in the past — race to honor the merits of artists whose work has been historically discredited or ignored due to their race, gender, or sexuality, Mehretu’s unwavering commitment to abstraction is itself an act of resistance. “Abstraction became so important to me because it’s this place where I have freedom of expression without the didactive reduction that certain types of representational work can suggest,” Mehretu said. Her decision to make work that isn’t limited to “informative” investigations of Blackness or queerness or Africanness is a refusal to comply with unspoken expectations of what African, queer, or Black art can or should be. “There’s a lot of desire in the country to reduce [people to] identities,” Mehretu said. “I’m interested in what’s possible when we come together as a collective and insist on one another’s protection and freedom.”