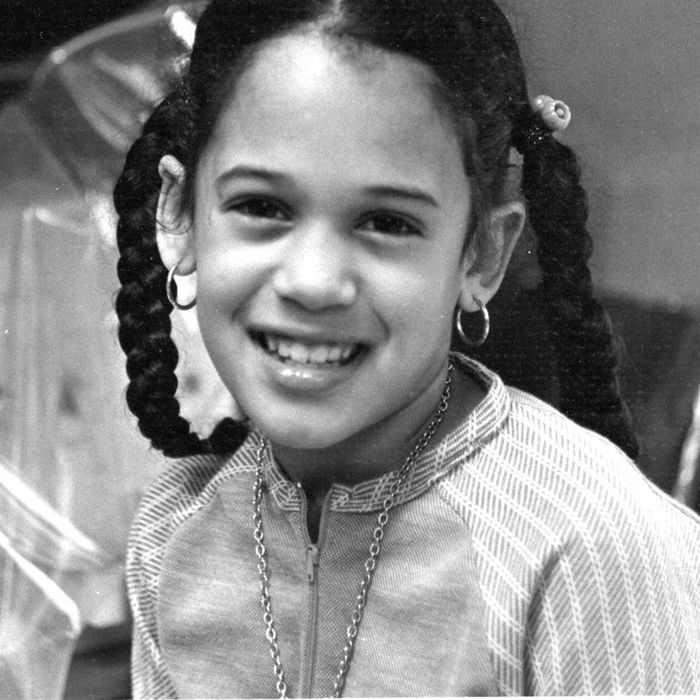

About a week before I met Senator Kamala Harris, she took former vice-president Joe Biden to task for his opposition to busing. “There was a little girl in California who was part of the second class to integrate her public schools and she was bused to school every day,” Harris said on the Democratic national debate stage. “That little girl was me.” The media ran the story along with a photo of Harris as a child — a little Black girl, hair in two poofy pigtails, looking straight at the camera like she was about to run for president that day.

I kept thinking of that photo the night I met her. How Harris’s resilience and moxie were there from the get-go, and how being a Black girl in America requires both.

I’d been invited along with a handful of other women journalists to join the senator for an off-the-record dinner at a restaurant on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. Radiant in stride, formidable in presence, Senator Harris took a seat at the table in the private room reserved in her honor — all ease and smiles, as if she’d just been called to family dinner. Harris has a beautiful, lyrical laugh up close, and she’s generous with it. She likes to laugh. Her sense of humor is threadlike in conversation, and I understood how useful it must have been for her growing up — and then later, as a presidential candidate — during a time of intense scrutiny over whether she was “Black enough.” As a self-serious Black girl growing up in all-white rural New England, I envied her that. I spent pretty much my entire youth defending and explaining, pushing away and clinging to my Blackness. It was a largely humorless endeavor.

Black girls grow up to be Black women, and that is made resolutely clear to us before we even learn how to spell “biracial.” I was 7 when a white girl tried to drown me at our local lake because I am Black. For Black women, racial reckoning and the fight to stay in the ring to dismantle systemic racism starts as soon as we leave the womb — whomever’s womb that may be, I might add, whether that womb belongs to a white woman (in my case) or a South Asian woman (in Harris’s).

Long before the overly commercialized Black Girl Magic mantra came into existence — in spite of the alarming rates at which Black girls are more criminalized and punished more harshly in schools across the country than their white peers — and long after it is forgotten, Black girls are forever the daughters of the words of Audre Lorde: “I recognize that my power as well as my primary oppressions come as a result of my blackness as well as my womanness, and therefore my struggles on both of these fronts are inseparable.”

After vowing all throughout my 20s that I was only ever going to marry a Black man, I ended up with a white guy, whose sense of humor (along with his self-awareness, good looks, great taste in music, and ease around conversations about race) is ultimately what won me over.

I asked her one question along these lines — defending your Blackness, and then ending up with a white husband — and although I can’t tell you her answer, because it was off the record, I can say that her response felt kindred in a way that I hadn’t anticipated. I was reminded of a similar revelation during the process of writing my 1997 book, Sugar in the Raw: Voices of Black Girls in America, a collection of interviews with American Black girls ranging in age from 11 to 18.

The impetus for the book was to understand individual Black girl experiences in America, because mine had been so isolated. What I found was a collective, living memory, breathing new life into old pain. It was beyond a sense of sisterhood, although it was that, too. There was this visceral, unfamiliar-familiar, meliorative feeling. A bounty of recognition, a heap of generative worth.

Several months after that off-the-record dinner, Harris dropped out of the presidential race. She wasn’t in the race long enough for me to know whether or not she was my candidate; to be honest, even as I felt lifted in her presence, I was cynical about the upcoming election. Three years of Trump had turned the presidency into a joke; no matter who went up against him, the end result would be a charade of political artifice.

A year later, when the pressure was on Joe Biden to choose a Black woman as his running mate, I felt less cynical, more plain worn-out. Of course this moment would hinge upon the where-and-when-I-enter of a Black woman. And then Biden chose Kamala Harris. It’s still politics, and Harris’s track record still deserves our criticism. But in that moment, the sense of kindred I’d felt with her coalesced with the all the voices of the American Black girls I’d interviewed years ago. It was like Harris was pulling all of us, including a younger version of me, into a possibly promising future. My heart felt full.