I’ve always loved the contrast between certainty and surprise. Shows happen with an inevitable rhythm. I might travel to the same city to sit in the same seat, in the same building, for the same brand, year after year. Routine but rarely boring—in a good season, I am rejuvenated by the ideas behind a show or the smart use of double-faced wool. I find there’s always something to enjoy and hopefully that eureka of recognition for a truly modern garment.

Of course, never has there been a year like this: completely adrift, everything canceled, factories shuttered, no customers. For what few shows will go on this season, I will not be traveling. That doesn’t mean nothing has been happening. The people I most respect in the industry did not waste this spring and summer, even if their workflow was wildly disrupted. I wanted to survey them about the future of fashion but also its recent past—what works and what doesn’t.

Turns out they wanted to talk too. For a tight-lipped bunch of creative people, I found them uncharacteristically open to speaking freely. The first interview took place in mid-May and the last in mid-August. I checked back in with most of them multiple times.

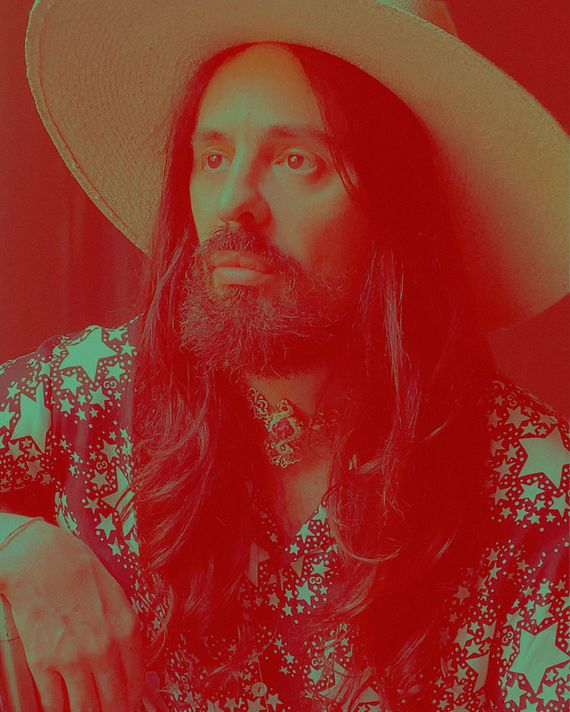

In some cases—Demna Gvasalia of Balenciaga, Alessandro Michele of Gucci, and Kerby Jean-Raymond of the American brand Pyer Moss—I discovered a dimension to their work that I hadn’t previously realized. One surprise was how often the retired Belgian designer Martin Margiela came up. In addition to my conversations with them individually, these designers talked to, and about, each other admiringly. Common themes emerged: enjoying having a moment to cook and recharge. Gripes about the acceleration of production and design cycles. A lack of support for new talent. The universal recognition that things need to be more inclusive.

It seems inevitable that once people are free to circulate again, there’s going to be an explosion of creativity and self-expression. Call it “Cathy’s Logic” or simply Newtonian physics, but all the pent-up energy and emotion will mean a new excitement for live performance, new restaurants, and a renewed interest in style. The Roaring ’20s followed the last pandemic, after all.

History provides a good way to understand both the fervor for fashion and the feeling that the industry has lost its center of gravity. The 19th century brought the rise of mass culture—through the invention of department stores, the proliferation of magazines, and the advent of all-powerful designers. The 20th century accelerated that phenomenon, and the 21st ushered in the total disruption of it. That explains why designers who became stars in the late 1990s (many of whom still hold top positions) nowadays express concern that they have lost control of their world. To an extent, they have.

It’s also true that designers never had as much control as a customer might think—they’re always beholden to their bosses to some degree. They can press for diversity on their runways and in their studios, for instance, but it’s clear that meaningful adjustments must come from the chairman and chief–executive levels. I called Michael Burke, the CEO of Louis Vuitton, who remembered getting resistance to hiring Virgil Abloh as the men’s artistic director: “Beyond Bernard Arnault [the chairman of LVMH], I didn’t have too many people in my corner—inside and outside. So it’s going to be a long ways. And in Europe, it’s going to be even longer, because you have the additional bias that is religious that you don’t have in the U.S. Our biggest minority in France is Muslim.”

Burke, who is American, told me emphatically, “The CEO has to set the stage and has to make decisions that are understood by everybody, and everybody understands there’s no going back.” Two years ago, he promoted a woman—over a list of male candidates—to run Vuitton’s French ateliers, which, with more than 3,000 employees, make up its largest division.

“It’s taken eight years to make a difference,” he told me. “Most CEOs are in a job for three, four years. And if you really want to do something culturally important—if you want to do something for Black talent or gender equality—it’s going to take you ten years. So with most executives, you’re not going to be around to get the credit for it. And that’s another reason it doesn’t happen.”

That’s a pessimistic view, perhaps, though I can see the challenges are real. And yet the ways we’ve all adjusted to the circumstances of the past six months make me think change can happen faster. It’s dazzling to imagine what things will look like a decade from now. But I relished spending time with some of the leading designers right now, at such a strange moment in time. There was one more thing we could all agree on: Sweatpants are not the future.

Read all of the interviews here:

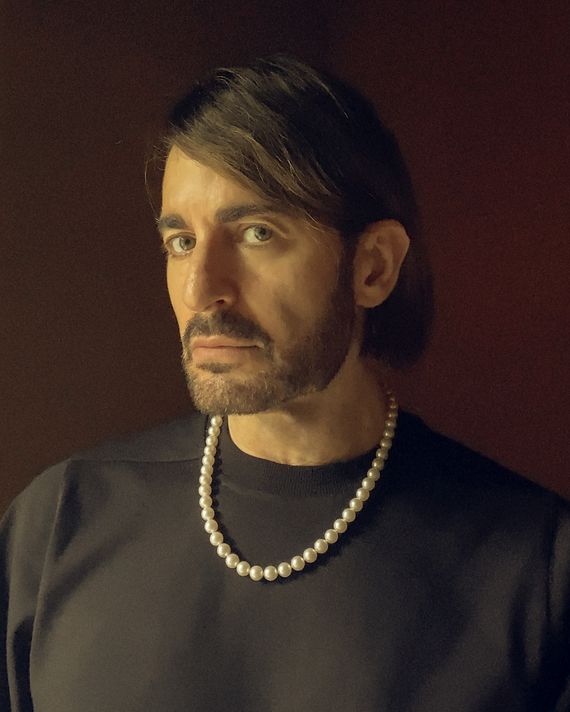

Marc Jacobs Is Putting On His Heels and Going for a Walk in the Real World

Demna Gvasalia Discusses Fashion With His Shrink Every Week

Rick Owens Knows He Shouldn’t Say This, But …

Raf Simons Hasn’t Worn a Piece of Fashion in Months

Kerby Jean-Raymond Is Not Interested in the Scraps

Rei Kawakubo Didn’t Stop Working for a Minute

Alessandro Michele Owns 35 Editions of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Clare Waight Keller Knows That Time Is the Greatest Luxury

Nadège Vanhee-Cybulski Is Ready for the Nurses to Take Over Instagram

Nicolas Ghesquière Just Wanted to Stay in California

Reed Krakoff Is Looking for a New Design Language

Stella McCartney Might Not Recognize You Anymore

Miuccia Prada Is Too Wise for Post-Pandemic Predictions

*A version of this article appears in the August 31, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!