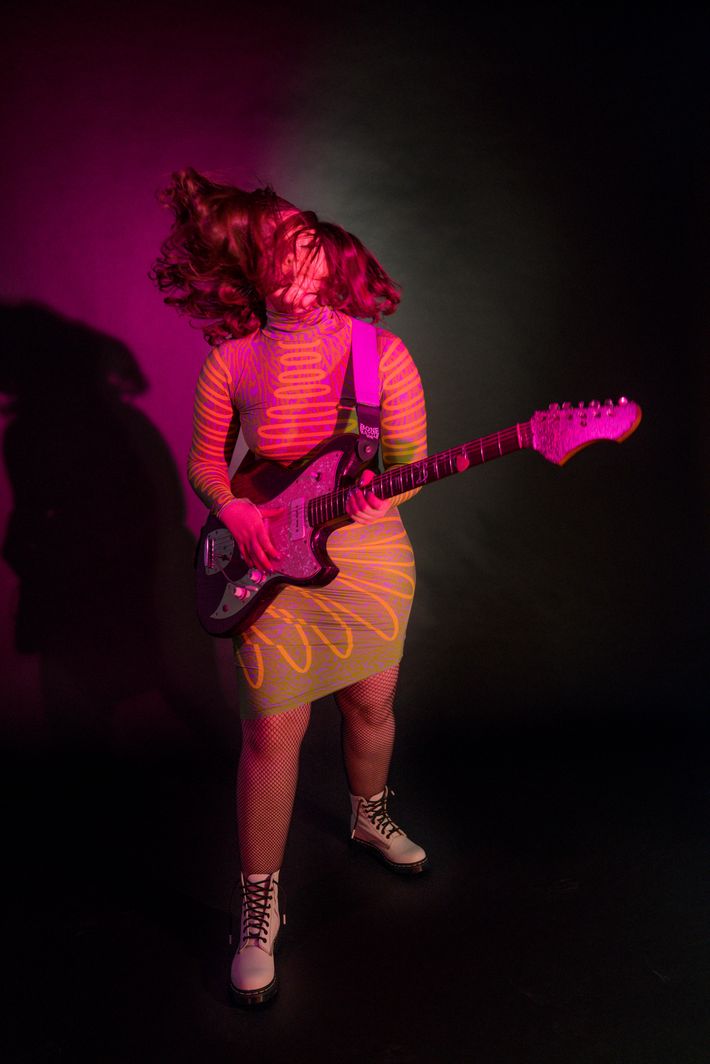

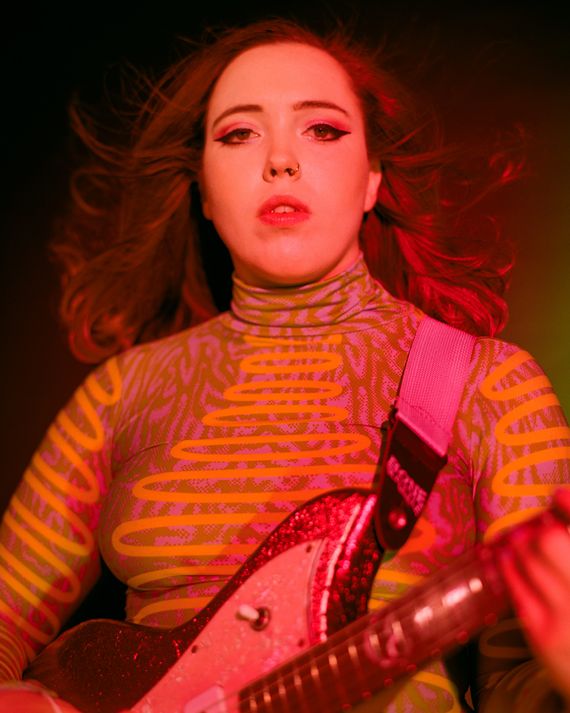

Outfitted in grungy fishnets, an array of glittery hair clips, and a black satin slip dress layered atop a long-sleeved T-shirt, the dream of the ’90s is alive for Sophie Allison — never mind the fact that the 22-year-old musician who records as Soccer Mommy was only alive for about two and a half years of that decade. Actually, maybe that’s the point.

“I love ’90s stuff, I love early 2000s stuff,” she tells me one drizzly Thursday in mid-February, lounging on a couch in her publicist’s Manhattan office. “I feel like that’s because that was the culture when I was, like, a 5-year-old. I was imagining being a teen and being a young adult and how cool it was going to be. So I feel like that’s why I, and a lot of people my age, have this attachment and nostalgia for that kind of stuff. It’s what we looked up to when we were kids.”

It’s also a time in her life that Allison found herself reflecting upon when writing the songs on her excellent new album, Color Theory (which, like her personal style, harkens back to the days of dreamy, female-driven alternative rock, à la the Breeders and Liz Phair). “I was thinking about being younger and how I’ve changed, how I might have thought I’d be and how I didn’t turn out that way,” she says. The ten songs that comprise the record are even more ambitious and panoramic than her 2018 breakthrough Clean; they toggle between Allison’s childhood and her current reality, while plumbing the depths of her family history to better understand her own mental health. “It’s a half-hearted calm, the way I’ve felt since I was 13,” she sings on the opener “Bloodstream,” a tuneful and raw reflection depression and self-doubt.

Over the years, though, Allison has come to embrace — or at least aestheticize — her dark side. She giddily describes her bedroom, in the Nashville house she shares with her boyfriend, as a “gothic haven.” She paints me a picture: ornate black canopy bed, purple velvet drapes, a vintage Dracula: Prince of Darkness poster (1966), and “this really cool candelabra that’s all black.” She’s scored most of these finds at antique stores, which is why we find ourselves making the journey into the rain to a hidden-away midtown antique store called Furnish Green. Though anything she buys must be small enough to fit in her luggage (probably no more candelabras, then), Allison is undeterred. “Hopefully I can find something tiny and goth I can grab for the room.”

Allison grew up in Nashville, and the first song she ever wrote — on a toy plastic guitar, when she was 5 — had a title worthy of that town: “What the Heck Is a Cowgirl?” She graduated to a proper six-string not long after, but she didn’t start sharing her music with other people until her teens. “Releasing to a wide audience feels so much less like you’re naked than tweeting out a song to all your high-school friends when you’re 15,” she says. “When I started putting stuff on my Tumblr, I was definitely more worried about people seeing it and thinking it was stupid.”

Suffice to say, they didn’t, nor did the indie label Orchid Tapes, which released her jangly, lo-fi collection For Young Hearts the summer after her first year in college. Allison had come to New York and was enrolled for a time in NYU’s music business program, but she quickly found that her own career was outpacing what she was learning in school. “We’d be learning how to book a show [in class] and I’d be like, I already have an agent,” she says with a laugh. Eventually, she left school to focus on her music full time.

When she’s writing a song, Allison sometimes associates it with a particular color. It’s not quite full-blown synesthesia, she explains, but “I’ll kind of imagine in my head a music video, or album cover, or something that’s very mood and color-based.” Color Theory takes this one step further. The record moves through three distinct sections, each organized around a hue and what it signifies: blue for melancholy and depression, yellow for physical and emotional illness and, finally, gray for darkness, emptiness, and loss. Heavy stuff, sure, but Allison’s lilting voice and buoyant melodies give Color Theory an inviting atmosphere.

The gray and yellow sections, in particular, find Allison grappling with her mother’s chronic illness. Ten years ago, when Allison was 12, her mother was diagnosed with cancer. “It was a hard surgery and a long recovery, and that was the hardest part to watch,” she tells me. “But when I was really young, I was very emotionally stunted, and I was just like, I’m not going to deal with this. So I just kind of stuffed it down and ignored it.”

Her mother has been reacting well to medication lately, but her chronic condition is still on Allison’s mind — especially when she’s far from home on the road. “There’s still this constant threat that it could change at any time, because it’s never going to go away. So when I started touring, it would pop up in my head more often because I was gone all the time and I wasn’t seeing her.”

And so she did what she’s been doing since she was a 5-year-old cowgirl with a plastic guitar: She wrote her way through it. The centerpiece of Color Theory, a seven-minute slow burner called “Yellow Is the Color of Her Eyes,” digs up all that buried emotion and turns it into something profoundly moving. (Her Smell filmmaker Alex Ross Perry directed the gold-saturated video.) “And I could lie / But it’s never made me feel good inside,” Allison sings. “I’m still so blue.” By the final verse, Allison finds herself confronting the inevitability of her mother’s death, in language that’s both poetic (“I’m thinking of her from over the ocean / See her face in the waves, her body is floating”) and disarmingly straightforward (“Loving you isn’t enough / You’ll still be deep in the ground when it’s done”). All the while, her guitar chords swell with the calming ebb and flow of the tide. The whole effect is unbelievably cathartic.

As we end our slow loop around the antique store, Allison has admired quite a few oddities that she’ll never be able to take with her: a decorative 1970s TV, an entire library-card-catalogue cabinet, and even (with a combination of fear and interest) a taxidermy tarantula. She settles on an amber-scented candle. On our way out, she eyes some kitschy 1950s-housewife books that remind her of her mom’s ironic sense of humor: She loves to collect all sorts of outdated tomes “about how women are crazy and stuff like that,” Allison says. I ask her if she’s played the album for her mom yet, and she indicates that she’s not quite ready for that. “I gave her the album and was like, ‘Have fun, uhh …. Don’t talk to me about it!’ I just don’t like getting sappy, especially with my family.”

In the multihued music she’s come to make as Soccer Mommy, though, Allison has found a way to articulate and expunge emotions that are more complex than just “sappiness.” Perhaps a song for her mother was easier — or maybe just more expressive — than having a conversation with her. This realization suddenly seems to wash over Allison, who pauses before adding, “I was like, you can have the album and that’s all I need to say.”

This article has been updated.

*A version of this article appears in the March 2, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!