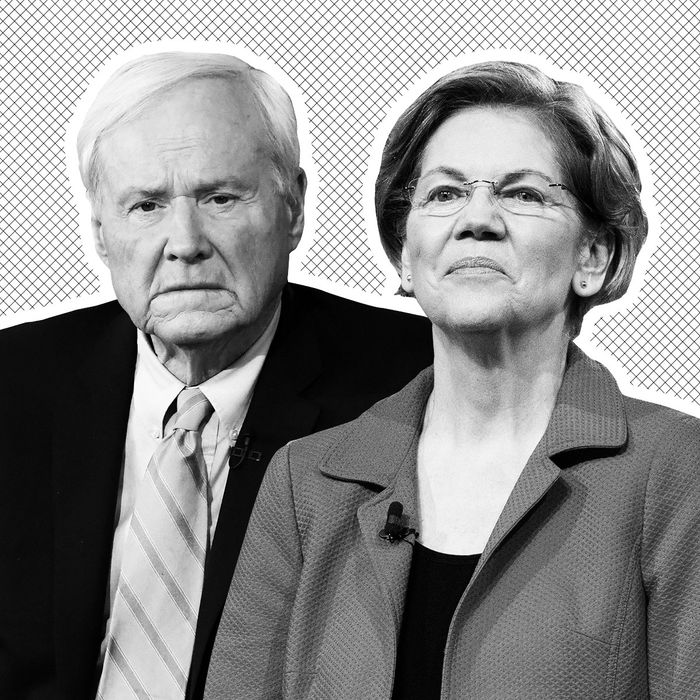

Chris Matthews finally contributed something meaningful to 2020 political analysis on Tuesday night when, during his post-debate conversation with Elizabeth Warren, he put on display the very attitudes that have given rise to the controversial phrase “believe women.”

Matthews was questioning Warren about her citation, during the debate, of a 1998 lawsuit in which Sekiko Sakai Garrison, a former employee of Michael Bloomberg, alleged that upon hearing that she was pregnant, he suggested that she “kill it.”

In the post-debate interview, Matthews pressed Warren on this reference, which Bloomberg has denied, and denied again onstage when Warren brought it up, as if he simply could not believe his ears.

“You believe that the former mayor of New York said that to a pregnant employee?” Matthews asked. Warren replied, “Well, a pregnant employee sure said that he did,” and then, signaling that this exchange could go deeper, asked Matthews coolly, “Why shouldn’t I believe her?”

As Warren kept talking, recalling her own memory of not having been asked back to her job teaching special-needs students after she became visibly pregnant, Matthews’s brow furrowed with confusion.

Just as Warren was affirming that, indeed, “pregnancy discrimination is real,” he interrupted her: “You believe he’s that kind of person, who did that?” he asked. Again, Warren said, “Pregnancy discrimination is real,” and noted that the exchange they were having on air was itself part of the larger pattern that has permitted this kind of unfair treatment to continue, even after it became officially illegal in 1978, noting how often she has heard, “We can’t really believe the women. Really? Why not?”

But Matthews was living the dream — of continuing to not believe it. “You believe he’s lying?” he asked.

“I believe the woman …” Warren said.

“You believe he’s lying,” Matthews interjected, just making triple sure.

“… Which means he’s not telling the truth,” finished Warren.

Then came Matthews’s Big Question: “Why would he lie? Just to protect himself?”

Warren: “Yeah.” And then, “Why would she lie?”

“I just want to make sure you’re clear about this: You’re confident about your accusation,” Matthews went on, as if Warren were making the accusation herself, and not making reference to another woman’s robustly documented claim.

“Look, all I know is what she said and what he said, and I’ve been on her end of it in the sense of discrimination based on pregnancy. It happens all across this country and men all across this country say, ‘Oh my gosh, he never would have said that.’ Really?”

The exchange was notable in the context of Matthews having recently been under fire for his bad punditry: Over the weekend he compared Bernie Sanders winning the Nevada caucus to the Nazi invasion of France (he has since apologized to Sanders); last summer in a post-debate interview he pressed Kamala Harris on her account of having faced racism in her life, asking, “How did you come out of that and not have hate toward white people generally?” Matthews’s history of covering Hillary Clinton was wretched; he once referred to her as “Madame DeFarge”; said in 2008 that “the reason she’s a U.S. senator, the reason she’s a candidate for president, the reason she may be a front-runner is her husband messed around”; and in 2016 was caught on camera, just before interviewing Clinton, joking about her slipping her “that Bill Cosby pill I brought with me.”

But his back-and-forth with Warren hit straight at the heart of issues well beyond his own horserace missteps. Coming the day after Harvey Weinstein was convicted on two counts of rape and sexual assault on the strength of women’s testimony, after years of a social movement built around women’s stories of bias, harassment and assault being taken more seriously, and in the midst of an electoral political season in which women’s purported unreliability has been the subject of discussion while a lot of men’s dishonesty has gotten a pass, Matthews made absolutely clear how desperately inconceivable it is to imagine that a powerful man … might lie.

Here was an extremely bright spotlight shone on the often murky concept of what it means to “believe women.” The phrase, which gets bandied about a lot in feminist circles, is one that I have long thought of as compelling but flawed. It gets heard (and used) as a clumsy imperative — often recast as “believe all women” — and as such it is deeply problematic. After all, we know that women can and do lie; an argument that we should always believe them has long, I feel, enfeebled the far more important argument that we should encourage them to speak more, and listen to them more seriously when they talk.

But the way that Matthews was simply undone by the suggestion that Michael Bloomberg, the billionaire former mayor of New York City, might be lying himself, was a sharp reminder that the very idea of believing women doesn’t have to be an imperative; at its most radical, it is a long-overdue corrective to the benefit of the doubt that powerful men are given over and over and over again.

Questions of power and believability are deeply intertwined: Whose word is reflexively taken seriously? For Matthews, and for so many people who watch him, the notion that a powerful man might have an incentive to lie in order to protect his power is far harder to grasp than the idea that a less powerful woman might lie to advance her own interests.

Women who describe experiences of sexism are so regularly cast as doing it for their own benefit (even though there is scant evidence that complaining of marginalization accrues any benefit to the marginalized and plenty of evidence that those complaints incur further harm) that it would likely never occur to Matthews, as it does to Warren, to really wonder why a woman like Garrison would lie about an experience like pregnancy discrimination.

But the default assumption of good faith falls so easily to a wealthy, powerful man who has many friends in media and politics, that — even though Bloomberg’s lengthy record of alleged discriminatory remarks have been reported on at length in the Washington Post and the New York Times; even though Bloomberg’s company has faced other claims of pregnancy discrimination; even though Garrison’s “kill it” allegation was made under oath; even though less than ten days ago a named witness, former Bloomberg employee David Zielenziger, confirmed to the Washington Post that he had heard Bloomberg make the remark, thus meeting a burden of proof that Bloomberg himself once articulated by asserting that the way he’d believe a rape claim was if there was “an unimpeachable third-party witness” — even with all that, Chris Matthews could still express shock, on the air, at the notion that Bloomberg might be “that kind of person” and wonder, out loud in front of people, why he would lie!

Power provokes trust; a comparative lack of power provokes suspicion. Consider that one of the only twisted contexts in which women’s claims of sexual harassment and assault have been consistently believed is when they have been leveled by (more powerful) white women — women who have often in fact been lying — against (less powerful) black men, then used as justification for racial violence and lynching.

But when Matthews expresses on television his absolute befuddlement at the idea that Bloomberg, a man who is running for president and who settled the legal claim brought against him by Garrison, would have a material interest in not telling the truth about a difference of opinion, he puts on display exactly the power dynamics that have left so many women who make claims of bias understood to be untrustworthy. And when Warren asks him in return, simply, why we shouldn’t believe the woman who has told the story of bias, she makes clear why the suggestion that we treat more women’s voices as legitimate doesn’t have to be a blunt and clumsy mandate in order for it to be a crucial step that could advance how we understand and correct abusive power dynamics.

Perhaps the grimmest thing about all this is how amazingly meta it is! Because Matthews wasn’t the only one to treat Warren as if she were making this allegation against Bloomberg herself, and as if her claim were suspect. During the debate itself, moderator Gayle King responded to Warren’s citation of the Garrison case by asking incredulously, “Senator Warren, that is a very serious charge that you leveled at the mayor … what evidence do you have of that?”

Warren’s answer (“Uh, her own words?”) was correct, but incomplete in the context of the debate. Warren was making reference to an amply documented allegation, but was treated, in front of a national audience, as if she were the one making a claim that is explosive and thus heard as inherently un-sturdy.

It’s a reflexive assumption of dishonesty that has plagued Warren and other female candidates throughout their campaigns for the presidency; in this cycle, Warren has had her own story of pregnancy discrimination treated as unreliable and been called a liar by a competing campaign and a phony and a fraud by television pundits and critics. There are, of course, always reasonable questions to be asked about candidates’ honesty and there’s no reason to think that Warren should be treated as unimpeachable. But the degree to which a perception of untrustworthiness has accrued to her and not to, say, Joe Biden, who has a very lengthy reported history of plagiarism and truth-stretching and who this week has been found to have repeatedly told some wackadoo tall tale about being arrested while trying to visit Nelson Mandela is telling. Joe Biden routinely benefits from why would he lie perplexity; Warren regularly gets taxed as untrustworthy and asked to present receipts, for her own claims as well as others.

(These very issues aren’t just relevant to the presidential primary. In Texas this week, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi offered her support for the reelection bid of conservative Democrat Henry Cuellar, a man who has also been accused, in court, of having fired an aide after she became pregnant. Cuellar’s primary opponent, Jessica Cisneros, is among those who publicly defended Warren when she was questioned about her own story of discrimination, tweeting, “It is way past time we took pregnancy discrimination, pay equity, and paid family & medical leave seriously in this country. Period.”)

That this should happen in part at the hands of a media that is itself so deeply embroiled in the results of a horrifically imbalanced system of trust and abuse is especially rich. Matthews himself has been accused of verbally harassing an assistant; he works at a network at which executives have been alleged to have made liberal use of NDAs to cover harassment and assault allegations. Debate moderators Gayle King and Norah O’Donnell’s former co-host at CBS was Charlie Rose, accused by more than 30 women of grotesque harassment; their former CBS boss, Les Moonves, left the network after having been accused of decades of harassment and abuse, and again, the network used NDAs to obscure that history.

It’s all so circular and suffocating. And for those who feel it, it’s worth going back and listening again to that exchange between Warren and Matthews last night. In the midst of it, you’ll hear the presidential candidate say a sentence that gets swallowed by Matthews’s voluble non-comprehension.

What she says is, “I’m just really tired of this world.”