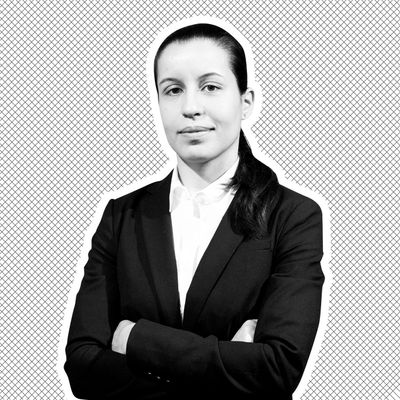

“The corrupt Queens political machine doesn’t want me to win,” Tiffany Cabán says in her first campaign video for Queens district attorney, which went viral after its release Thursday. “Your next DA could be a career politician or a career DA. Or your next DA could be a public defender. Who do you trust?” Cabán, who has defended over 1,000 clients from prosecution by the DAs office, is hardly your typical candidate for district attorney. But the 31-year-old queer Latina raised by working-class Puerto Rican parents wants to change the system from the inside; she supports decarceration, ending cash bail, decriminalizing sex work, and favors a holistic “trauma-informed” approach to justice. Cabán’s commitment to challenging the status quo (the other front-runner in the June 25 race is a longtime politician and former real-estate lobbyist Melinda Katz) has earned her support from fellow DSA-backed progressive Ocasio Cortez, who has endorsed only one other candidate since taking office. “New Yorkers deserve a seat at the table, and a champion who will fight to realign our priorities towards equal treatment under the law,” Ocasio-Cortez said. “If Tiffany Cabán wins, things are going to change”.

I spoke to Cabán on my podcast about what separates her from the field and how her own personal life shaped her outlook. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why are you running for Queens DA?

One of the reasons I’m running is because everyone in the field is calling themselves a progressive prosecutor to the point where it’s lost all of its meaning. I like to talk about decarceral district attorneys. Getting into this race for me has to do with my experience as a public defender, my experience as a Latina woman coming from a low-income household, in neighborhoods that were over-policed, and over-criminalized. I’ve learned through my personal and professional experiences that we are pretty much being sold this false promise of safety from our DA’s office, and perpetuating a lot of the historical oppression and marginalization of the same groups. I see a real opportunity to transform that system and do some better work

Can you tell me about your approach to trauma-informed justice?

My personal history brought me into public defense work, and ties into why I do what I do and how I approach my advocacy for my clients. The communities that have been so devastated by our criminal-justice system, by the prison industrial complex, are the same communities that historically experience trauma at higher rates and have the least amount of access and fewer resources. I make it a little personal when I’m talking about a client or advocating for a client and looking for a just outcome. I talk about where they came from and why.

I know that it’s privilege — access to resources like therapy and education that separates me from my clients. It’s not about good people or bad people. The question is how we can take better care of people so they have the tools in their tool box to change behavior.

Because not everyone has access to therapy.

It’s good if you can access it but it’s something that not everyone can afford and so the question is what does the rest of the world do if they don’t have access to it.

What has your experience with trauma been like?

It ties into why I do what I do and how I approach my advocacy for my clients. I grew up in Queens and my parents grew up in NYCHA housing, in the Woodside houses. My grandfather was a man who was pretty physically abusive to his family. He was also somebody who struggled with alcoholism, to the point where my grandmother left him and my mom dropped out of school to help take care of the family. After I was born, when I got a little bit older, my grandfather was declining in health — he’d been essentially drinking himself to death. When he came back into our lives, he was incredibly patient, loving, and kind. He was my favorite person on the planet … As I got older, thinking about how this really abusive father and husband turned into a loving amazing grandfather.

He was a Korean War combat veteran and had earned a purple heart … He came home from the War with PTSD. He self-medicated with alcohol.

Where were our systems in place to support him so that he could support his family? And that’s the way I think about it when I’m representing somebody. It’s not just how their contact with the criminal-justice system affects them but also how it affects their family, their entire family tree.

What made you want to go to law school?

I went to law school wanting to be a public defender. As public defenders, we create these really intimate relationships and we want so badly to help our clients and their families and communities as best we can. And our goals should be the same goals and metrics for success as the DAs office: one, how do we reduce recidivism, how do we keep crimes from occurring, because we don’t want our clients cycling in and out of the system; how do we decarcerate, how do we keep people rooted in their communities. You learn as a public defender that stability equals public safety. Stability keeps people out of the system.

As you said, it’s become politically expedient to run as a “progressive.” You call yourself the only “decarceral DA.” How do you differ from other people who are running for Queens DA?

I’m not a career prosecutor who has perpetuated the system that we’re now saying needs to be reformed, or a politician who has never stepped foot inside of criminal court. Historically, the DA’s office has been a place where they’ve decided on so many things, but our communities know best. And I’m the only candidate out there saying full decriminalization of sex work. Why? Because it saves lives. Why? Because our sex-worker community is calling for it. Harm reduction and safe consumption sites. Why? Because it saves lives. And that is again simply from being in the community, listening to those who are directly impacted and making a commitment to say that our policies are going to be made with those who are directly impacted at the table.

What will you do about police and prosecutorial misconduct?

Nobody is above the law, and that means holding police officers accountable when they step out of their role and hurt others. Prosecutors work with police officers on a daily basis when they’re prosecuting cases so it’s really important to make sure we have a robust independent prosecutorial unit to keep it completely separate. We need to make it untenable for bad officers to stay on the job.

As for prosecutorial misconduct, one of my biggest concerns is something called the Brady Rule. Any time there is information in a case that could be used by the defense, it must be turned over and it must be turned over immediately. The problem is prosecutors are their own gatekeepers and so it’s really hard to even catch this kind of misconduct — if we find out about it, we found out by accident. If folks are committing Brady violations they cannot stay employed. If they are engaging in bad tactics and gamesmanship, they cannot stay employed.

It’s really about changing the metrics of success for the DA’s office. We now measure success simply through numbers of convictions and length of sentences. But when you stop that and say, “This is a public safety job, this is about keeping people safe,” then you know that there are so many opportunities to be working with the defense and not just being adversarial for the sake of being adversarial. Because what do defense attorneys want? To keep their clients out of the system.

So what are some of the alternatives to incarceration that we could invest in?

I’m really proud to have the support and endorsements of folks like Make the Road and Vocal New York, which provide the incredible supportive services that actually change behavior and keep people safe. The women’s project does really great work with children. Cure Violence is incredible.

I had a client who was getting into a lot of assaultive behavior. He had gotten arrested a few times in the year and a half before I met him and each time he went to jail. Thirty days, 60 days, 90 days in jail, and finally I get him. He’s gotten into another fight. And the DA’s like, “Enough is enough! Nine months jail.” And I turn to the DA and I’m like, “You realize it’s just not working, right? You’re throwing him in jail for longer periods of time. He’s going back on the street and he’s still hurting other people. Let’s learn more about this young man.” And what I learned through working with our social worker was that he was somebody that was horribly physically abused as a child, somebody that had unhealthy relationship dynamics modeled for him and he didn’t have access to a lot of resources. So I said, “Why don’t we get him some individual therapy, because jail obviously isn’t working”?” And the DA’s response was, “Well, he should know better.”

If you told me years ago that I should know better about certain things, I could say intellectually, Yes. But did I have the tools in my toolbox to act differently? No. And here was an opportunity to actually change behavior, keep him safe and keep others safe.

During a Democratic town hall candidates were asked if people who are incarcerated should have the right to vote. Bernie Sanders said they should and Pete Buttigieg said they should not. I was wondering where you fell on that.

They should absolutely have the right to vote. There’s a lot of evidence that shows that empowering people by giving them a voice is critical to rehabilitative experiences. That is a restorative justice principle. If you want to call it a correctional system, at least in theory, then preventing folks from being able to correct the system — namely voice their beliefs in an election — is really just counter to that promise. You can’t in the same breath say, “I recognize our criminal justice system is racist, and it’s classist,” and then say, “And by the way, these folks don’t don’t deserve constitutionally protected rights.”